- Osprey Guide (Pandion haliaetus) - June 8, 2022

- American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) Guide - April 28, 2022

The osprey is the master angler of the raptors. Whereas other birds of prey often hunt for a variety of mammals, reptiles, birds, and insects, these highly specialized birds feed exclusively on fish.

Every aspect of ospreys is tailored for life on the water. They live and nest near open water; they use a unique hunting strategy for catching fish; even their feet are specially adapted for grasping wet and slippery prey. Fittingly, the osprey is also known by several aquatic-themed colloquial names including fish hawk, fish eagle, sea hawk, and river hawk.

As such unique birds, ospreys are endlessly interesting to observe. The famed naturalist John Audubon found ospreys remarkable, as he detailed in his 1829 species account:

“The habits of this famed bird differ so materially from those of almost all others of its genus, that an accurate description of them cannot fail to be highly interesting to the student of nature.”

Next time you’re near an open body of water, make sure to keep an eye out for these master fishers of the skies!

Osprey Taxonomy

The osprey family tree is a bit of a mystery, with no universally accepted taxonomic classification. As diurnal raptors (birds of prey that hunt during the daytime), ospreys share many characteristics with hawks, eagles, vultures, falcons, and caracaras: larger body size, strong sharp talons, and a deadly hooked beak. However, evolutionary scientists are unsure which of these raptors are most closely related to ospreys.

In general, diurnal raptors are split into two unrelated groups. Order Accipitriformes includes the hawks, eagles, and vultures, and order Falconiformes includes the falcons and caracaras. DNA evidence indicates that these two groups evolved separately, even though they share many traits.

Ospreys are often classified in order Accipitriformes, but this is not universally established. Since they are so highly specialized and unique among raptors, the evidence linking ospreys to either order is unclear.

Most taxonomists agree on one thing: Ospreys are weird. Whether they are grouped under Accipitriformes or Falconiformes, ospreys are usually classified in their own personal taxonomic family, Pandionidae. This family contains the singular genus Pandion, which contains the singular osprey species Pandion haliaetus.

Within Pandion haliaetus, four subspecies of osprey are generally recognized. These subspecies are very similar in appearance and habits, and mainly differentiated by geographic distribution.

How to Identify Ospreys

Main things to look for:

- Ospreys almost always hang out near an open body of water.

- In flight, ospreys have long, crooked wings that are mostly white below with a dark “V” and elbow spots.

- The osprey’s face has a dark bandit mask and ruffled “bedhead” feathers.

Appearance

Ospreys are large raptors, averaging 23 inches head to tail and weighing three to four pounds. As with most birds of prey, females are 15–20% larger than the males.

Osprey plumage is mostly dark brown above and white below. The head is mostly white with a dark stripe running through the eye like a bandit’s mask. The feathers on the head are often ruffled and scruffy, so it looks like the bird just rolled out of bed on a bad hair day. Ospreys plumage is not sexually dimorphic; males and females look very similar.

In flight, osprey wings appear long and crooked, forming an “M” shape. The wings are mostly white from below, marked with a dark “V” and large spots at the wrist. The ends of their wings are often splayed out when flying, so that the primary feathers look like outstretched fingers.

Ospreys are most easily confused with other large raptors like eagles or Buteo hawks. However, these birds lack the distinctive crooked wings with a dark “V” and elbow spots.

Adaptations for Fishing

The osprey body is highly adapted for hunting fish. Long legs help ospreys reach into the water to catch fish without getting entirely soaked, and osprey feet are large and covered with spiked scales that help grasp slippery fish.

Ospreys also have a special reversible toe. When perched, ospreys arrange their feet with three toes facing forward and their hallux (nerdy bird word for thumb) facing backwards. However, when hunting, ospreys rotate one of their toes to form a “zygodactyl” arrangement, with two toes facing forward and two toes facing backwards. This symmetrical grasp is particularly useful for grabbing fish.

Vocalization

Ospreys give shrill, repeated whistle vocalizations that could be mistaken for seagull calls. They often call while in flight or when alarmed. Their alarm calls can become quite frantic, especially if their nest is threatened. Males also call repeatedly while displaying for females in a “sky dance”.

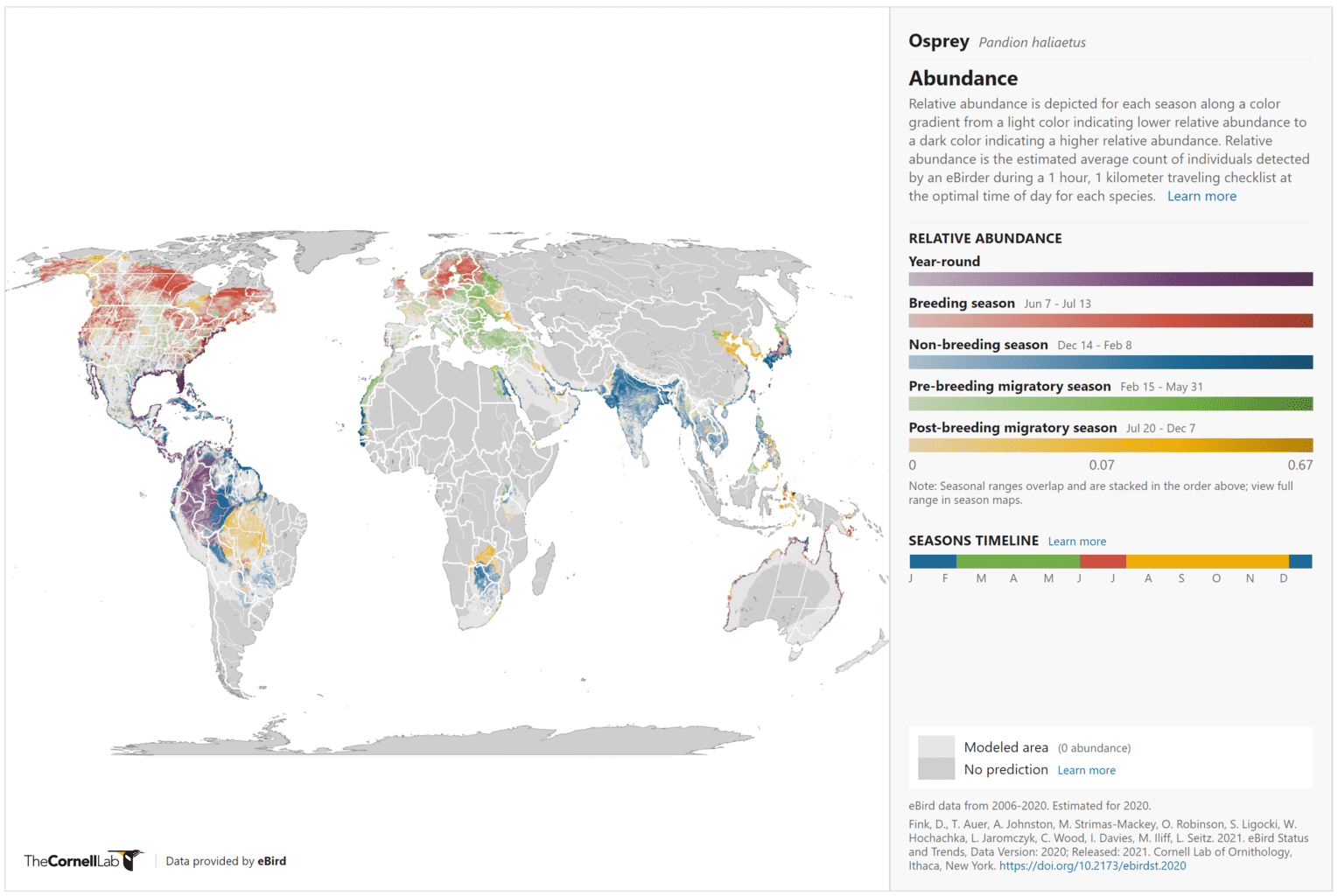

Osprey Distribution

Ospreys have a cosmopolitan distribution, meaning they live in appropriate habitats throughout the entire world. This is weird for a bird—only a handful of land-based bird species occur on every continent besides Antarctica.

Habitat

Since ospreys exclusively eat fish, they require habitat near lakes, rivers, or the ocean. Ospreys prefer open water habitats where they can search for prey from above, uninhibited by dense vegetation or other obstacles. Ospreys also prefer areas with extensive shallow water since they do not dive deep while fishing.

As long as open water is present, ospreys are not picky about their habitat’s climate and biome. These birds can be found anywhere from tropical coastline and salt marshes to lakes in the taiga and rivers in the savanna.

Migration

Osprey migration is strongly influenced by the accessibility of fish. As soon as a water source dries up or freezes over, ospreys will seek wetter, better fishing grounds.

Even if a water source is consistent throughout the year, fish populations usually fluctuate. Fish are cold-blooded animals that rely on their external environment to thermoregulate, so they control their body temperature by moving to warmer or colder water. When the weather starts cooling down in fall, many fish swim into deeper, warmer waters that are inaccessible to ospreys.

Northern ospreys migrate long distances in the fall while searching for adequate fish populations, ultimately overwintering in the tropics and subtropics. These birds can fly over 120,000 miles during their life.

Ospreys at lower latitudes can often support themselves year-round within a much smaller area and become non-migratory residents. These birds still move around as they look for the best fishing spots, often covering 250 miles within a year.

Population Status

Ospreys and many other birds of prey were under dire threat from the toxic pesticide DDT in the 20th century. DDT became popular during World War II as a cheap, effective, and long-lasting pesticide for controlling agricultural pests and vector-borne illnesses, but its harm to the wildlife and the environment quickly became apparent.

After several piecemeal regulations, the Environmental Protection Agency banned agricultural use of DDT outright in 1972. Agricultural use was banned internationally in 2004 under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.

DDT is toxic to most animals and accumulates in an organism’s body throughout its life. In a process known as biomagnification, DDT and other toxins accumulate especially quickly in predators’ bodies as they consume contaminated prey. The resulting high concentration of DDT is harmful to birds because it weakens eggshells. Shells can become so thin that they are easily crushed under the weight of a roosting parent.

Ospreys in New England were particularly hard hit by DDT, with some populations declining to 10% of their original levels. Although ospreys were never federally listed as an endangered species, several states passed legislation to protect osprey populations and help them recover from DDT. Ospreys also benefited from conservation actions targeting bald eagles and peregrine falcons—two other birds of prey that were highly impacted by DDT and considered federally endangered.

Osprey populations have successfully returned to healthy numbers in the past few decades. Many conservation efforts have focused on constructing artificial nesting platforms, which provide safe and stable spots for ospreys to raise their chicks. The osprey conservation priority is now listed as “least concern” by the IUCN Red List.

Osprey Life History

Diet

Ospreys are entirely piscivorous; over 99% of their diet consists of fish. They hunt for a variety of species depending on the area and season, but generally catch fish ranging from 6–14 inches long.

Hungry or bored ospreys may hunt for an occasional non-fish meal. Anecdotal observations have been made of ospreys eating everything from muskrats to mollusks, although this is highly unusual.

Hunting Behavior

Ospreys search for fish from an elevated vantage point, perching or gliding high above the water surface. Upon spotting a potential meal, they often take a moment to gauge their line of attack and hover in place by scooping their wings against the wind.

To catch their prey, ospreys dive head-first and feet-first all at the same time—imagine an Olympic diver in the pike position who fails to straighten out before plunging into the water. Upon grabbing a fish, the osprey takes a few strong wingbeats to reemerge from the water, often shaking off the water droplets in a ridiculous mid-flight shimmy.

The osprey’s head-and-feet-first hunting technique is only useful for catching fish swimming within a few feet of the surface, so ospreys are limited to hunting fish that school or swim in shallow water. The technique is variably successful, with ospreys catching a fish on 20-70% of dives depending on the osprey’s experience and the hunting conditions. This is pretty impressive if you imagine trying to catch slippery fish—with your feet!

To carry fish to their dinner spot or nest, ospreys grasp fish horizontally to their bodies with one foot in front of the other. Interestingly, individual ospreys show a preference for foot placement, with most birds adopting a regular stance (right foot in front) and occasional birds preferring to place their feet like a goofy-foot skateboarder.

Breeding and Nesting

Ospreys usually return to the same nest site to meet their mate year after year. They generally mate for life in monogamous pairs, although males will occasionally have multiple partners if they can defend an additional nest site located nearby.

Males usually arrive at the nest site first and guard the area until their mate arrives. Males woo females with a “sky dance” or “fish flight” around the nest site—swooping, hovering, and dangling their legs holding a gift of fish, screaming loudly all the while.

Ospreys are more versatile than most birds of prey when choosing a nesting spot. They build on anything that can support their huge nests—trees, snags, cacti, rock towers, sheds, utility poles, docks, cell phone towers, or artificial nesting platforms. Ospreys prefer sites that are close to water, in an open area, and difficult for ground predators to access.

As with eagle nests, osprey nests are sometimes called aeries. They consist of a massive lump of sticks, lined with softer materials like grass, seaweed, and bark. After several successive breeding seasons, an osprey nest can reach up to two yards across and four yards thick, easily large enough to fit a few human children.

Females usually lay three eggs, each about two and a half inches long and shaped like a chicken egg. Egg coloration can vary from creamy white to light brown with dark brown speckles or splotches. The eggs are incubated for five weeks, usually by the female.

Newly hatched osprey chicks—affectionally referred to as “osplets”—are covered with brown down that looks like a fluffy version of the adult plumage. This coloration is useful as camouflage, so that chicks blend into the nest when viewed from a distance. In contrast, the chicks of most other raptor species are initially covered in bright white down.

After hatching, osprey chicks start begging for food immediately. Dinner is a sequential family affair, with the male usually eating the head of a fish before giving the rest to the female. The female rips up the remainder of the fish, feeding the softest bits of fish to the nestlings and eating the rest.

Nestlings start feeding themselves after six weeks and take their first flight after seven or eight weeks. Fledglings hang around the nest for at least a few weeks while they learn how to hunt.

Predators

Adult ospreys have few predators, although they are more vulnerable when bathing or roosting for the night. Nile crocodiles in western Africa and caiman in South America occasionally kill ospreys. Rarely, bald eagles and great horned owls also attack adult ospreys.

More frequently, adult ospreys are harassed by other birds trying to steal a freshly caught fish. Bald eagles, seagulls, crows, and peregrine falcons often chase ospreys in the hopes that the harassed bird will eventually drop its fish.

Osprey chicks are much more vulnerable to attack. Many birds predate osprey nests, including bald eagles, ravens, goshawks, and great horned owls. Nests are also at risk to attack from the ground, especially by nimble climbers like raccoons. When possible, ospreys choose nest locations that are unreachable by climbing predators, often over the water or at the top of slippery poles.

Osprey FAQ

Answer: Ospreys usually live eight to ten years, although occasionally they live up to 25 years.

One of the oldest ospreys lived in Scotland and was known as the Lady of the Loch. Lady became beloved by many birdwatchers as she returned every year to the same nest, conveniently outfitted with a camera. Over her 27-year life, Lady bonded with four partners, laid 71 eggs, and fledged 50 chicks.

Answer: Ospreys have never been listed as federally endangered under the Endangered Species Act. However, osprey populations declined dramatically in the 1950s through 80s because of exposure to the toxic pesticide DDT, leading several states to list ospreys as endangered or threatened.

After the banning of DDT and persistent conservation action, populations have now returned to healthy levels. Most states have unlisted ospreys, but they are still protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Answer: Although ospreys usually hunt fish weighing one to two pounds, they occasionally will grab fish up to four pounds. The heaviest reported fish was 4.4 pounds—pretty impressive for a bird that usually weighs less four pounds itself!

When an osprey grabs a fish that is too big, they usually do not make it very far out of the water before letting go. Tragically, on rare occasions an osprey’s talons can become ensnared in the body of a large fish; if the osprey cannot fly off, it ultimately drowns.

References

Bierregaard, R. O., A. F. Poole, M. S. Martell, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.osprey.01

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2019). All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Osprey

Dunn, L., J. Alderfer, P. Lehman, M. Dicknson. (2002). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, fourth edition. National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., USA.

Sibley, D. A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds, second edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, USA.

Sibley, D. A., Elphick, C., & Dunning, J. B. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, USA.

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: