- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

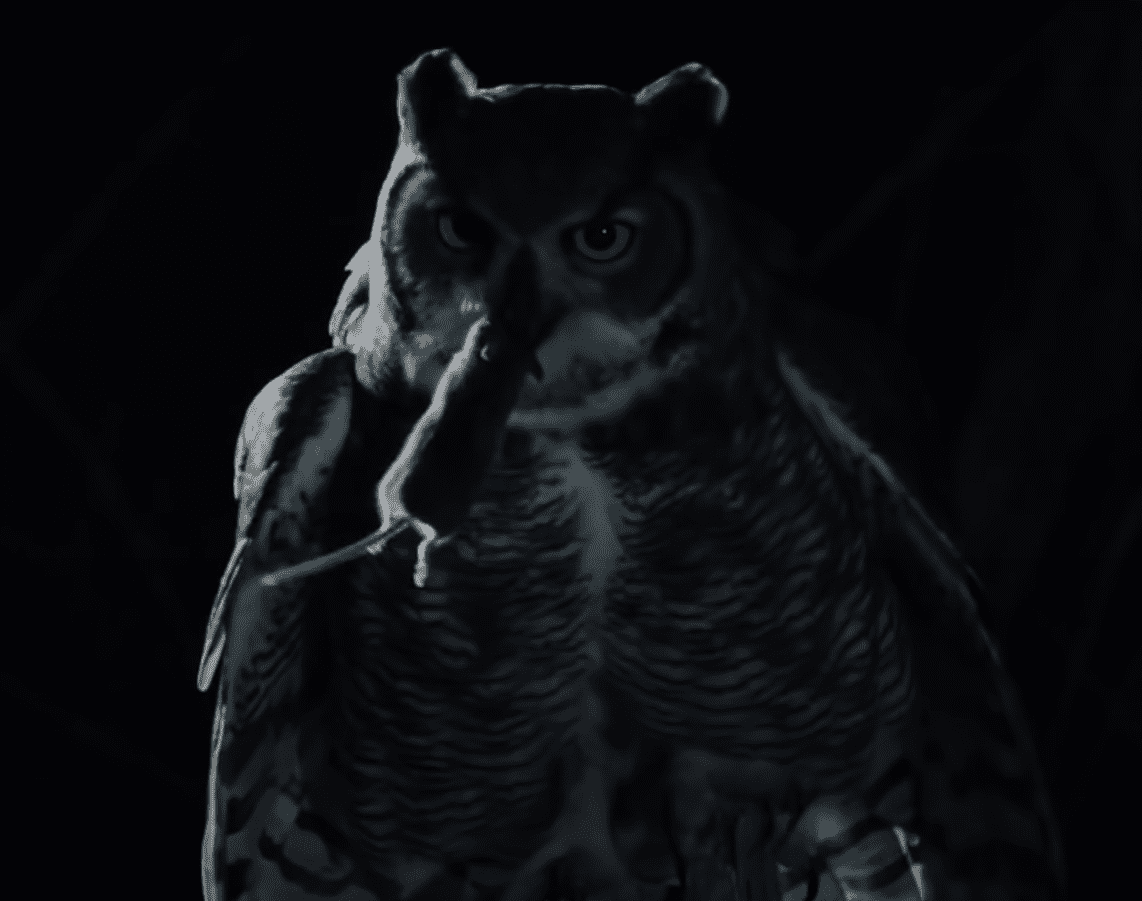

The Great Horned Owl is in the running for the most well-known owl out there.

Great Horned Owls have been the subject of fascination for centuries with their iconic cat-eared silhouettes, huge staring eyes, and resonant hoots. Their caricatures can be found on anything related to the night, and superstition still surrounds them.

While they should strike terror in the furry hearts of rabbits and rodents everywhere, there’s no need for us to fear them! It’s pretty cool to hear those deep hoots on a moonlit winter night – and even cooler to get a glimpse of these elusive nocturnal predators.

Whenever my resident pair turns up in the yard, I always stop to listen. Sometimes, when I’m lucky, I even get a good look!

Most people probably know what a Great Horned Owl looks like – but how do you find one? Keep reading, and I’ll break down how to locate, observe, and appreciate these captivating winged creatures of the night.

Taxonomy

The Great Horned Owl is a member of the order Strigiformes, which includes around 230 species of owls divided into two families.

Modern taxonomists consider the nighthawks and nightjars to be the owls’ most closely related cousins. Surprisingly, owls are only distantly related to the superficially similar falcons and hawks.

The family Strigidae, known as the true owls, contains most of the world’s owls in its 24 genera, including the Great Horned Owl, which falls under the genus Bubo.

Known as the horned owls in North America and the eagle owls in the Old World, the genus Bubo includes around 25 species – comprising most of the world’s largest living owls.

Due to their large size, striped chests, and reputation as fierce hunters, Great Horned Owls are also known as tiger owls, winged tigers, and tigers of the air. They are also called hoot owls.

Taxonomy At a Glance

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

Genus: Bubo

Species: B. virginianus

How to Identify the Great Horned Owl

The Great Horned Owl is pretty much unmistakable in most of its range. This makes identification a breeze!

Adults

The adult Great Horned Owl is a large bird. It is nearly two feet long, weighs almost three pounds (which is hefty for a flighted bird), and has an impressive almost four-foot wingspan. Their proportions are similar to the more familiar Red-tailed Hawk. When they fly, their wingbeats are rigid without obvious flapping, and they hold their ear tufts flat to their heads, making them invisible.

Great Horned Owls are a lesson in camouflage, with their entire bodies covered in earth-toned mottled, and barred feathers. They have pronounced facial disks outlined in black, V-shaped white markings above their eyes, and white “bibs” where the head joins the body. Their feet are large and feathered with distinctive gray talons.

They have large heads with noticeable horns, or ear tufts, on top. Ear tufts, also called plumicorns, are moveable and made of feathers. Their function is still unknown, but it’s thought that they break up the owl’s profile while roosting and are likely also used for communication with other owls. Altogether, their large heads, ear tufts, white eyebrows, and bright yellow forward-facing eyes give the impression of a scowling cat.

Male and female Great Horned Owls look similar, but females are slightly larger and heavier. On average, the female’s plumage is more brownish and has heavier mottling, although this is hard to discern when viewing birds at night.

Plumage coloration and size vary widely with the region, and around twenty different forms, or morphs, are documented. In North America, eastern birds have orange “faces” and more barring on the lower breast. Owls of the far north are more uniformly gray in coloration, owls of the southwest are larger and paler overall, and owls of the Pacific Northwest are very dark brown.

Immature Birds

Fledgling Great Horned Owls look a little bit like Muppets, with their heavy coats of grayish tan down and “smiling” faces. They also lack ear tufts. As their feathers emerge, they start resembling the coloration patterns of their regional form. Fledglings are often visible, perched near their nests, waiting for their parents.

Juvenile Great Horned Owls, encountered in fall, look like “fresh” versions of adults. Their feathers are brand new and not worn down yet, causing their barring to be more pronounced, tails more tapered, and flight feathers unblemished and pristine.

Great Horned Owl Vocalizations and Sounds

The quickest way to identify (and hopefully get a chance to see) a Great Horned Owl is to listen for their distinctive hooting.

Territorial Hooting

Male Great Horned Owls issue a series of three to eight deep-pitched hoots, with the second and third hoots being slightly shorter and the second to last hoot a tad longer. There is some variation from owl to owl, but generally, it will sound like “hoooo hoo-hoo hooooooo hoooo.”

Hooting is most common right after dusk or before dawn when owls emerge from and return to their daytime roosts. Great Horned Owls are very territorial, and males hoot primarily to announce their territory to other owls. During the breeding season, from late fall to mid-winter, hooting can be heard all night and often increases after midnight.

Females also hoot during this time, but their voice boxes are smaller than males, so their hoots are higher in pitch. Listen for the duets of Great Horned Owls, in which deep male hoots and a higher-pitched female answers. While males can be heard year-round, female Great Horneds only hoot for around seven to ten days per year during active courtship. After this, they become too busy incubating and raising young.

Other Sounds

Great Horned Owls make a few other strange sounds. While courting, female owls will answer male hoots with a loud, nasally “Guh-waaaaay!” that can make you jump out of your skin if you’re in the woods at night.

On occasion, Great Horned pairs will engage in caterwauling, in which both owls issue a rapid series of barks, squawks, hoots, and shrieks at the same time. This usually happens during courtship or when a nest is threatened.

Young owls produce a variety of raspy and wheezy begging calls that include whines, screeches, and barks. These can sound similar to the call of the Barn Owl.

Fledgling and adult Great Horned Owls will perform bill clacks and wailing whines when a defense is posturing at potential threats.

Where Does the Great Horned Owl Live: Habitat

Range

Great Horned Owls are widespread all across North America, from Mexico to the subarctic regions of the extreme north. They occur sporadically in Central America and are again widespread throughout Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru in South America.

Habitat

Great Horned Owls are extremely adaptable and accept a wide range of habitats. They can be found in most forests (coniferous, deciduous, mixed, and tropical) and streamsides, mangrove swamps, deserts, subarctic tundra, prairies, rocky coasts, pastures, parks, and even cities.

Their preferred habitat contains a mix of open areas (for hunting) and covers (for nesting and roosting). For this reason, they avoid large areas of open desert, unbroken grassland, tundra, extremely populated city centers without parks, and very dense old-growth forests.

Great Horned Owl Migration

Great Horned Owls are not migratory, and individuals will often live in the same territory year-round for their entire lives. However, they may travel greater distances when feeding young, and owls in the extreme north may move slightly southward to find food in winter.

Young owls must leave their parents’ territory and disperse to find their own. These “floaters” often hang around just outside other owls’ territories.

Great Horned Owl Diet and Feeding

Great Horned Owls are formidable hunters who will eat any animal they can successfully overpower but prefer mammals.

Mammals

Rabbits and hares are favorite prey items for Great Horned Owls. They can even take down black-tailed jackrabbits that weigh up to six pounds. Rats, mice, squirrels, voles, marmots, opossums, bats, raccoons, armadillos, young foxes and coyotes, domestic cats, and prairie dogs are also eaten.

Due to their lack of a well-developed sense of smell, great Horned Owls are one of the few animals able to prey on skunks. As a result, many individuals smell powerfully of skunk spray. On occasion, they even attack porcupines – which is only successful sometimes. All in all, Great Horned Owls have been known to eat around 200 different species of mammals.

Birds

Birds are also taken, usually ambushed on their nests or while roosting at night. Favorites include larger species like geese, ducks, pheasants, grouse, turkeys, and birds that nest in the open like crows and ravens – but any bird caught unaware is fair game. Nestlings are particularly vulnerable.

Great Horned Owls will readily attack and eat any raptor smaller than them, including Cooper’s Hawks, Prairie Falcons, and other species of owls. They have even successfully killed larger birds of prey like Ospreys and Red-tailed Hawks. It is estimated that they prey upon around 300 different species of birds.

Other Animals

Great Horned Owls are very opportunistic and prey on snakes (including rattlesnakes), lizards, frogs, baby alligators, giant insects, scorpions, and spiders. They have even been observed capturing and eating larger fish species, like carp.

Carrion

Great Horneds have also been observed feeding on animals that are already dead, such as roadkill. In the far north, they will often store animal kills for later, incubating the carcasses to thaw them out for consumption.

Great Horned Owl Breeding

Great Horned Owls nest earlier than most North American birds, making use of the longer winter nights. This gives them an advantage, as they get first dibs on prime nesting sites, out-competing the later nesting Red-tailed Hawks and Ospreys. It also gives their young more time to learn crucial life skills before their first winter.

Courtship

The breeding season starts as early as October in southern parts of the range and as late as early April in the far north. It begins in October or November throughout most of North America, adding more spookiness to the Halloween season. In all cases, it begins with the male’s emphatic hooting.

Male Great Horned Owls use several prominent perches within their territories and will perch atop these, lower their bodies until they are horizontal, stick their tails straight up, and puff their white bibs out while hooting. These are all visual cues that work well to impress females in low-light settings, as, unlike other birds, Great Horned Owls live in a world of black and white. If you hear hooting outside in mid-winter, check the tops of power poles and tall trees to catch a glimpse of this spectacle.

Females will answer the male’s hoots with their higher-pitched equivalent, and the two will duet. This duetting is typically only heard for a seven-to-ten-day period each year – usually in December and January – about one to two months before the eggs are laid. Females will occasionally issue a loud “guh-waaaaaay!” call in response to the male’s deep hooting. Due to their nocturnal life, vocalizations are likely the most important component of the courtship.

The male Great Horned Owl will offer prey items to the female, which they will eat together. Courting male Great Horneds will also perform a simple display flight that involves flying straight up and repeatedly returning to the perch. He will then attempt to rub bills with her while bowing if things are going well. This often leads to allopreening, where the two birds groom the feathers of each other’s heads and then mating.

Check out this video, which shows most of these behaviors in action.

Great Horned Owls are typically monogamous, staying together for the duration of their relatively long lives, but will choose another partner if their mate dies. There is a recent instance of one male mating with two females – this is thought to be rare, but it’s an area that is worth more study.

Established pairs will “renew their vows” each year with a brief courtship before raising young together. Outside of the breeding season, they are primarily solitary and rarely affiliate with each other.

Great Horned Owl Nesting

Great Horneds never build their own nests. Instead, they search their territories for old nests of other large birds – primarily raptor nests, like those of the Red-tailed Hawk and Osprey, raven nests, Golden and Bald Eagle nests, Great Blue Heron nests (sometimes even among a colony of breeding herons), and, in the desert, Harris’s Hawk nests in cacti.

They will also use cliff ledges, tree cavities, manmade structures, palm trees, old buildings, patches of witch’s broom in trees, broken tree stumps, old badger and coyote dens, and even the bare ground. Of all North American birds, Great Horned Owls are the most flexible regarding nest site preferences.

Male Great Horned Owls typically select the nest site and direct the female’s attention by flying straight up and stomping on it. They prefer locations 15 to 70 feet off the ground without barriers to allow for easy access.

Once selected, the pair will roost together at the chosen nest site for months before the eggs are laid. Sometimes they will pull feathers from their breasts to line the nest, but that’s about as crafty as they get.

Great Horned Owl Eggs

The female typically lays two to three eggs, with two eggs being the most common and up to six eggs being rare. Eggs are white, elliptical, slightly glossy, and have a somewhat granular texture.

The female Great Horned does most of the incubating while the male brings her food, but he will also take over himself on occasion. Incubation starts with the first egg and takes about 28 to 37 days.

Great Horned Owl Nestlings

The owlets hatch over a period of days. They are altricial – primarily naked and helpless – with pink skin and gray bills and are covered in fluffy white down. The female broods the young for their first three weeks of life while the male brings all the food. She rips the meat into smaller pieces and offers it to the owlets.

At 10 days old, the young open their eyes. They remain in the nest until they are about five weeks old, with both parents constantly hunting to keep them fed. If an owlet – often the last to hatch – is too weak, it will often starve to death and be fed to its stronger siblings.

After five to seven weeks, the young begin “branching” – climbing out of the nest onto surrounding branches and structures. They first attempt flight at around nine weeks old but aren’t good at it until after 10 to 12 weeks.

Once fledged, the parents continued feeding them for several months. The young constantly observe their parents, learning most of their survival skills and behaviors between two weeks and two months of age.

Juvenile birds stay with their parents as long as possible, often not leaving the territory until they are forced to do so when the next breeding season starts. The young owls must then disperse and find their own territories. This first year is the most dangerous one of their lives – 50% of young Great Horned Owls don’t survive to adulthood. At two years old, they become sexually mature.

Due to the high demands of feeding the young, Great Horned Owls only produce one brood each year.

Great Horned Owl Population

Great Horned Owls are common and widespread throughout their large range.

Their extreme adaptability and preference for fragmented habitats has allowed their numbers to remain stable over the years, even in the face of urbanization. So long as nest sites and prey remain available, this trend should continue.

Partners in Flight currently estimates a population of 5.7 million Great Horned Owls throughout the Americas.

Is the Great Horned Owl Endangered?

The Great Horned Owl is not currently endangered. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists the species as having a status of Least Concern, meaning it is not at immediate risk for extinction.

This wasn’t always the case, as Great Horned Owls were heavily hunted in the mid-20th century due to the erroneous belief that they preyed on domestic fowl. While a Great Horned isn’t above snatching an errant chicken when the opportunity presents itself, they actually feed on chickens far less than raptors – mostly because chickens are safely in their coops at night. Intense poaching once led to the Great Horned Owl being listed as endangered in Michigan.

Great Horned Owl Habits

Great Horned Owls are nocturnal and have large territories of one to six square miles, so observing them is always a real treat. Knowing their common behaviors can help increase your odds of a sighting!

Territorial Defense

A hooting male is usually the most obvious sign of a territorial Great Horned Owl. Listen for hooting right after dusk and just before dawn year-round, or wait until fall and winter when vocalizations become more frequent.

Males usually perch on tall, conspicuous fixtures like trees, power poles, and cliffs. Look for his tell-tale silhouette and flashing white throat patch. Owls are creatures of habit and will use the identical “sing posts” every night.

Both male and female Great Horned Owls are viciously territorial and will attack intruders. Typically, a physical attack is reserved for other Great Horned Owls or large raptors, like falcons and hawks. However, if a person or dog gets too close to a nest site, the pair may swoop aggressively. Urban owls are usually pretty forgiving of such transgressions, allowing close approaches and easy viewings.

An owl on the attack will first spread its wings, fan its tail, lower its head, clack its bill, hiss, and emit wailing cries in what is known as a threat posture. If this isn’t enough to deter the attacker, the owl will rush forward and lash out with its strong feet or lay back with its talons aimed at the attacker. It’s best to avoid these feet.

Hunting

Great Horned Owls hunt by perching in prominent locations throughout their territory and watching for prey. They fly from perch to perch, scanning for movement below. Once a target is sighted, the owl will swoop down and pursue it with slow, deliberate flight. Specialized wing feathers with fuzzy tops and fringed leading ledges enable owls to flight so quietly their prey doesn’t stand a chance. Sometimes, owls will even walk along the ground to chase smaller prey.

Great Horned Owls close in on their prey with their powerful talons, which can exert 28 pounds of pressure. This is usually enough to quickly puncture small animals and sever the spine of larger prey, but if not, the owl will bite the face and head.

They will usually swallow their prey whole on location, but if it’s a larger animal, they will remove the head, wings, and legs and crush the bones to make it easier to carry back to a safe perch. Sometimes, they will stash large kills in trees for later.

Most hunting takes place at night, but when desperate or feeding young, they may occasionally make a kill during the day.

Roosting

At dawn, owls return to their daytime roosts to sleep. Great Horned Owls prefer shady, protected spots to rest. Dense coniferous trees are favored, but they will also roost in other large trees, snags, hollows, caves, and thick shrubs. While the female is on the nest, the male will roost nearby. Resting owls make their bodies as tall and slim as possible, erecting their ear tufts to further disguise their profiles.

It’s remarkably difficult to spot a well-camouflaged sleeping owl by yourself. But, if you happen to notice a flock of crows gathering and cawing angrily, check for a Great Horned Owl. Crows have learned that Great Horned Owls frequently kill their nestlings and mob roosting owls to drive them out of their territories.

Owls also cough up pellets after feeding. These pellets – full of hair, bones, and feathers – accumulate on the ground and can be a dead giveaway that there is an owl roost nearby.

Great Horned Owl Predators

Not much messes with an adult Great Horned Owl. Bald Eagles and Golden Eagles can kill them, but it rarely happens due to their opposing shifts. Oddly enough, the biggest threat to a Great Horned Owl is another Great Horned Owl. Owl-on-owl fights are ferocious, and if an intruder loses a battle, he is often eaten.

Domestic cats, coyotes, crows, ravens, foxes, bobcats, raccoons, opossums, and bears will eat eggs and nestlings, but it’s a risky endeavor. Owlets that fall to the ground too soon are at the greatest risk.

Great Horned Owls can be their own worst enemies, occasionally attacking prey, they can’t handle. Some have lost their lives to porcupine quills and venomous snake bites, and others have been rendered blind by skunk spray.

Other threats include collisions with vehicles, barbed wire accidents, electrocution from powerlines, and the effects of rat poison. People still shoot Great Horned Owls in many areas, although it is now illegal.

Note: Avoid using poisoned bait traps to kill mice and rats. Great Horned Owls feed on poisoned rodents, and the toxins accumulate in their bodies, eventually leading to paralysis and death. They also feed the meat to their young, which can be lethal to them.

Great Horned Owl Lifespan

Great Horned Owls have the longest lives of all North American owls. The oldest known wild, Great Horned Owl, lived to be at least 28 years old, but their average lifespan is about 13 years.

After they leave their parents’ territory, the first year of life is the hardest, and most juvenile owls don’t survive. If they make it to adulthood, they will likely live a good long time.

In captivity, Great Horned Owls can live to be 50 years old.

FAQs

Answer: Great Horned Owls are very opportunistic and will take anything they think they can overpower. That said, their heaviest prey usually weighs around six pounds. This means most adult dogs are safe. If you have a puppy or small breed, be cautious – especially at night. All cats are at risk unless you have a very large one. Keeping your pets indoors at night is the best way to avoid an owl attack.

Answer: Great Horned Owls find a safe, secluded place to roost during the day. Typically, they will find a dense tree like a pine. But they will also roost in palm fronds, tree cavities, old buildings, thick shrubs, and even in caves. Because of their superb camouflage, it’s tough to spot a sleeping owl.

Answer: Great Horned Owls have one to six square miles of large territories. If you want one to choose your yard, make sure you have suitable habitats for hunting, like an un-mowed field and some large trees or dense vegetation for roosting and nesting. Pastures at the edge of forests are ideal habitats.

You can also offer water – owls get much of their hydration from prey but will seek out ponds and large birdbaths for drinking and bathing in the summer. Make sure the birdbath is at least two inches deep and sloped to allow easy bathing. Also, keep your yard dark – overly illuminated areas can deter this nocturnal hunter.

Research Citations

Books:

Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

Mikkola, H. (2014). Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide. (2nd Edition). Firefly Books.

Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sibley, D.A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds (2nd Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Sibley, D.A. (2020). What It’s Like to be a Bird. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Online:

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds:

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: