- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

Few who have heard the loud, baritone hooting of the male Barred Owl issuing deep from the woods on a still night or been startled by the rowdy caterwauling of a pair in the middle of the dark forest are likely to forget the Barred Owl.

I certainly remember hearing the whole forest come alive with loud spooky laughter and creepy chatter only to realize that it was not, in fact, a gaggle of witches but only two Barred Owls!

More often heard than seen, these highly vocal woodland owls are easiest to find by listening. Keep reading and I’ll break down how to find, watch, and enjoy these ferocious songsters of the night forest.

Taxonomy

Barred Owls are members of the order Strigiformes, which includes all of the world’s owls in two families: Tytonidae and Strigidae.

The family Strigidae is made up of around 230 species of true owls in its 24 genera, including the genus Strix, which is named for the vampiric owl monster of myth that sucked blood from babies.

While that sounds a little intense, the 23 owl species in the genus Strix pose no threat to infant humans – but small mammals should definitely beware! Known as the wood owls and the earless owls, these are strong, medium to large sized nocturnal forest-dwelling owls that lack ear tufts. Often, their unique and complex vocalizations provide the key to their identification.

The Barred Owl, Strix varia, was originally described by Benjamin Smith Barton, a naturalist from Philadelphia, in 1799. Its common name refers to the many crisscrossing linear markings found on its feathers. Barred Owls are also known as old eight-hooters due to their characteristic eight-note songs.

Taxonomy At a Glance

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

Genus: Strix

Species: S. varia

How to Identify the Barred Owl

If you’re in North America and you encounter a decent sized owl with no ear tufts and dark, solid-colored eyes – odds are you’ve found a Barred Owl. They are easy to distinguish from the eared, yellow-eyed Great Horned Owl, which shares most of its range, but can be confused for the closely related Spotted Owl in the Pacific Northwest.

Adults

Adult Barred Owls are medium-sized to large owls – they are significantly larger than the screech owls but are smaller than the Great Horned Owl. They are compact and stocky-bodied, with rounded heads that lack ear tufts. The bills and feet are yellow, although only a small portion of the toes is visible due to their heavily feathered feet, which end in large gray talons.

When perched, they stand one to two feet tall and have relatively long wings, giving them an impressive wingspan of three to four feet. Barred Owls fly with slow, deliberate wingbeats and occasionally glide.

Their large, dark brown to black eyes are distinctive and are set fairly close together in the facial disk, which is bordered by black stripes that extend to the top and back of the head. The facial disk is a uniform gray to brown and the eyes are not bordered by dark “eyeshadow” markings, which separates them from other owls in the genus Strix.

The feathers of their backs are primarily brown to gray, punctuated by many white crescent-shaped markings. When viewed from behind, their middle tail feathers feature three to five pronounced horizontal white bands. Overall, their fronts are lighter in color, with the feathers of their upper breasts forming a shaggy scruff and featuring many long, vertical dark markings. This gives their top halves a darker appearance than their lower breasts, which are pale with a few dark, streaked markings. This heavy plumage barring is what gives the Barred Owl its common name.

Females and males are very similar in appearance, with the female being slightly larger – males weigh around 1.6 pounds while females can weigh up to 2.5 pounds. Males also have darker facial plumage, but this difference is subtle and difficult to discern without viewing a pair side by side.

Four subspecies have been described based on slight variation in coloration and size. Subspecies varia is the most widespread form in North America and represents a middle-of-the-road gray-brown color. Subspecies georgica occurs in the southeastern United States and is smaller in size. Subspecies helveola is a lighter, cinnamon brown in color and occurs in southeastern Texas. Subspecies sartorii occurs in Mexico and is considerably darker in color than the others.

Spotted Owls look very similar to Barred Owls, but their lower breast is marked by small, round, dark markings rather than long streaks – they are spotted rather than barred. Spotted Owls are also noticeably smaller than their Barred cousins. Barred Owls hybridize with the Spotted Owl where their ranges overlap in the Pacific Northwest. Hybrid birds blend features of both species and can be challenging to identify.

Immature Birds

Very young owlets are covered in grayish white down. As their plumage begins to come in, they take on a shaggy barred appearance. “Teenage” Barred Owls with their recently acquired adult plumage appear very “fresh” and lack the worn feather edges of older adult birds. The center tail feathers of juvenile Barred Owls feature four to six white bands.

Barred Owl Vocalizations and Sounds

Barred Owls are very vocal owls and their unique hooted songs and calls are the easiest way to identify them.

Territorial Hooting

The loud, deep-pitched eight-hoot song of the male Barred Owl carries well in the dense forest and can be heard from a half mile away. From a distance, it may sound like a large dog barking. But up close, it sounds like the phrase, “who cooks for you, who cooks for you allllllllll.” The second “you” spikes up in pitch, and the long, drawn out “alllllll” has a warbling, whinnying quality to it. Males often repeat their song several times per session, advertising their territory boundaries to rivals from several different perches.

Check out this video of a Barred Owl hooting:

Barred Owls will also frequently issue a loud, two note “HOOOOO-ahhhhhhhh” that dissipates into a whinny before drifting away. This is known as an inspection call, and is issued when two owls are getting close to one another. Since they are nocturnal birds living in deep woods where visibility is always reduced, vocalizations are key to their communication. It’s not uncommon to hear a “HOOOO-ahhhhh” during the day as well, especially in overcast weather.

Vocalizing is most frequent from late January to early April before the nesting starts and again in the fall when the young disperse. But Barred Owls will hoot year-round, most often right after sunset.

Both males and females hoot, but the female’s voice is higher-pitched due to her smaller voice box and her end hoots tend to ring out longer. Males and females will also duet with one another, where one hoots and the other answers.

Caterwauling

Occasionally, male and female Barred Owls of a pair will engage in an extra raucous duet known as caterwauling. This involves both owls’ releasing a chaotic, nonstop barrage of every sound in their arsenal, including cackles, barks, hoots, cat-like wails, whoops, deep-wind up murmurs that rise to extra emphatic “HOOOO-ahhhhs, and raven-like gurgles at the same time. Sometimes multiple pairs will join in, creating a deafening cacophony. These events have been described as “demonic” and “monkeyish” – and some people even become convinced that a bunch of witches are cackling while performing a ritual nearby. It’s particularly alarming for the fact that it often erupts out of nowhere in the quiet night forest.

Listen to caterwauling Barred Owls in this video:

While many owl species duet when in a monogamous pairing, this level of caterwauling appears to be unique to the Barred Owl. One of the most intense and wonderful birding experiences you’ll ever have is listening to a pair of Barred Owls letting loose in a caterwaul.

Other Sounds

Barred Owls also issue high-pitched chittering calls, barks, screeches, wails, growly mumblings, and gurgling sounds similar to those of the Common Raven. Young owls screech and hiss when begging for food. Barred Owls of all ages will hiss and clack their bills when agitated.

Where Does the Barred Owl Live: Habitat

Range

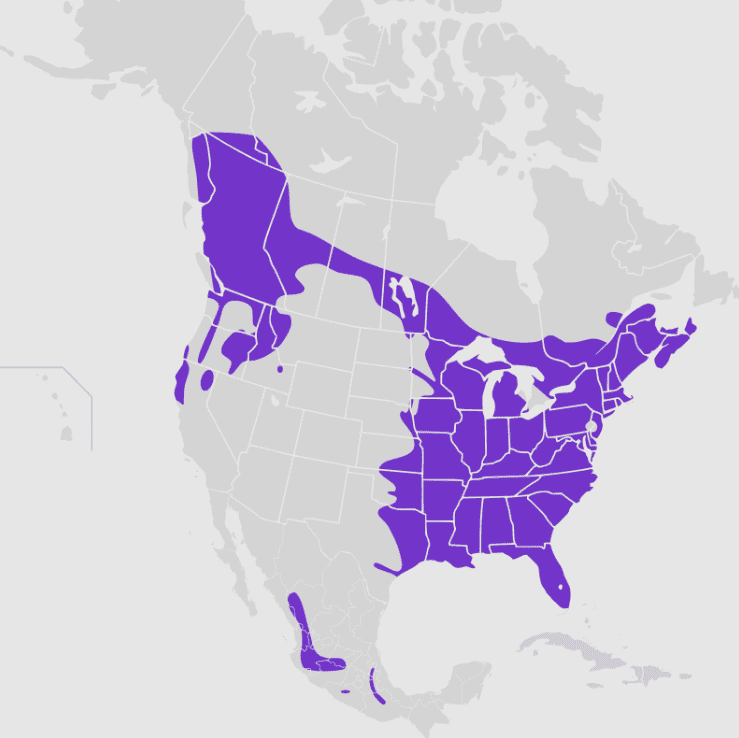

Once confined to the eastern half of North America, the Barred Owl has been expanding its range west for the last century, following routes created by the environmental alterations of humankind. Today, they occur throughout eastern North America, west to Texas, and throughout most of Canada all the way up to the tree line. They have also moved into the Pacific Northwest and can now be found from Washington to northern California. Their range also extends south to southern Mexico.

Habitat

Barred Owls require large, unbroken sections of mature forest near a water source that can support populations of their prey and provide suitable nesting locations. They are pretty flexible about the type of forest, and thrive in deciduous hardwood forests, old growth forests, oak savannah, cabbage palm forests, swamp woodlands, wooded river bottoms, coniferous forests, and mixed forests.

They are fairly adaptable owls, and will move into large parks with old trees, open wooded areas, suburban neighborhoods, and even logged old growth forests so long as there are some tall trees and an open understory.

Barred Owl Migration

Barred Owls are year-round residents in all parts of their range. While owls in the extreme north may wander slightly south in the winter to locate prey and young birds will disperse out of their parents’ territories in fall, most Barred Owls never stray more than six miles from their chosen territories and live their entire lives in a small radius.

Barred Owl Diet and Feeding

Barred Owls are adept and opportunistic nocturnal hunters that feed mostly on small mammals.

Mammals

Small nocturnal mammals like mice, voles, pocket gophers, shrews, moles, mountain beavers, and flying squirrels make up the bulk of the Barred Owl’s diet. Bats are also taken, sometimes right out of the air. They will occasionally hunt during the day, which gives them access to squirrels and chipmunks as well.

Larger mammals are also hunted, with the biggest prey being the three-pound snowshoe hare. Opossums, rabbits, skunks, domestic cats, and, on rare occasion, porcupines are also eaten.

Birds

Barred Owls will flush roosting birds at night and take both adults and young. They will also target nesting sites of Barn Swallows, Cliff Swallows, and Purple Martins in spring and gorge on nestlings. Woodland thrushes, like the Veery, Wood Thrush, and Varied Thrush, are a favorite, as they rise early to sing before dawn and are easily captured while unable to see in the dark.

Other owl species smaller than the Barred, such as the screech owls, Northern Saw-whet Owl, Long-eared Owl, Flammulated Owl, and Northern Pygmy Owl, are also frequently taken, especially those that share the night. There have also been a few instances of the smaller, less aggressive Spotted Owl becoming prey.

Barred Owls are opportunists. While they do take the odd songbird or Calliope Hummingbird, they mostly feed on hapless nestlings and recent fledglings. That said, they are bold hunters and have been known to take down raptors like Cooper’s Hawks, Sharp-shinned Hawks, and Snail Kites as well.

Other Animals

Barred Owls eat more insects than other owls of their size. On occasion, they will “hawk” insect prey by gulping them right out of the air or visit outdoor lights and feast on the insects gathered there. Larger prey is further supplemented with snails, slugs, earthworms, frogs, salamanders, snakes, lizards, and young turtles.

They are also known to fish by diving from above or even wading into shallow water. This gives them access to crayfish and crabs in addition to fish.

Carrion

Barred Owls have been observed feeding on road killed squirrels and deer but this is rare.

Barred Owl Breeding

The Barred Owl breeding season begins in late February and continues until mid-July. Females especially become fierce while nesting, and a close approach of the nest or young can be greeted by bill clacking and, sometimes, divebombing and talon-first attacks.

Courtship

The male Barred Owls begins the courtship process by raising his wings half way, bobbing his head, and bowing at his paramour. Females will often reciprocate these gestures. If things escalate, they will engage in allopreening, where they groom each other’s faces and heads, and will eventually mate. Barred Owls mate frequently in late winter to ensure success.

Once paired up, the two will roost together, call to one another while perched close together, and perform duets. The male will also bring her food offerings. The female often becomes lethargic just before egg-laying, and the male feeds her frequently during this time.

Barred Owls typically mate for life, but will find a new partner if their mate dies.

Barred Owl Nesting

Like most owls, Barred Owls do not build their own nests. Instead, they must scout suitable preexisting nest sites on their territory. This can sometimes take a full year.

Barred Owls prefer to nest in cavities in deep woods with a developed understory and a water source, and will search for hollow trees or broken snags. If these are not available, they will use stick nests of other birds, like Red-shouldered Hawks, crows, and ravens. They will also use old squirrel nests, nest boxes, and, on rare occasion, the bare ground.

It has yet to be determined whether the male or female selects the nest site. But once it is chosen, only a few slight alterations are made: squirrel litter may be stomped down to create a flat surface for the eggs, debris may be dug out, and simple materials like lichen, tree branches, and feathers may be added as a lining. Favorite nest sites will often be used year after year.

Barred Owl Eggs

The female typically lays two to three eggs, rarely up to nine in years when ample prey is available – although it is rare that all nine offspring survive. The average clutch size is two eggs.

Eggs are smooth, white, slightly glossy, and less round than the eggs of other owl species. The female handles incubation solo, sitting on the nest for 28 to 33 days while the male brings her food. Incubation starts when the first egg is laid, so there is often a large disparity in the ages of the young.

Barred Owl Nestlings

After the young hatch, the female continues to brood and guard them for another three weeks. The male hunts for the entire family, bringing prey that the female then feeds to the owlets. The hatchlings are altricial, meaning they hatch naked and helpless with closed eyes, and are covered in white down. On their seventh day of life, they open their eyes.

When they are just three to four weeks old, the owlets begin climbing around the nest and female joins her mate in hunting to feed them. Sometimes, they fall from the nest tree. While this usually ends in tragedy, Barred Owl chicks are capable of “climbing” back into the tree by using their talons and beaks to grab the bark, scrabbling up by flapping their wings for momentum.

By week 10, they attempt their first flight although flying is not finessed until week 14. They fledge 36 to 39 days after hatching. The parents continue to feed them for several weeks, and they learn how to hunt for themselves by observing their parents.

Fledged owlets stay with their parents for four to five months before striking out on their own in the fall. If they survive their most dangerous first year, they will raise their own young at the age of two to three years.

Due to the high demands of feeding and raising the young, Barred Owls only produce one brood per year – and will forego breeding if prey is scarce. Mated pairs will raise offspring together for a decade or more.

Barred Owl Population

Barred Owls are the second most abundant owl in North America right behind the Great Horned Owl. While they may be experiencing a slight decline in the south due to the destruction of swamp habitats, elsewhere they are expanding their range each year.

Partners in Flight estimates a global population of about 3.5 million owls, with the majority of these being found in the forests of Canada. The North American Breeding Bird Survey estimates that the population of Barred Owls has increased by 1.1% per year between 1966 and 2019.

Is the Barred Owl Endangered?

The Barred Owl is not endangered. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists the species as having a status of Least Concern, meaning it is not at immediate risk for extinction. In fact, they have expanded their range significantly over the last century, moving from eastern North America to colonize most of the Midwest and Pacific Northwest.

Historically, the Great Plains created a natural barrier for this woodland owl that avoids large areas devoid of trees. But human colonization created patches of trees that the Barred Owl quickly moved into. This, combined with the fire suppression regime of the early European-American settlers allowed the Barred Owl to move westward, traveling along the Missouri River and other riparian corridors where it was protected from raptors of the open country.

The Barred Owl reached the Pacific Northwest in the mid 1900’s and began wreaking unintentional havoc on the smaller, less aggressive, and already endangered Spotted Owl of the old growth forests. Barred Owls are larger and significantly more aggressive, often outcompeting Spotted Owls in their preferred old growth forests. They also harm the species’ gene pool by hybridizing with them.

For these reasons, biologists have actually considered creating a Barred Owl culling operation in the Pacific Northwest.

Barred Owl Habits

Barred Owls blend easily in to the dense, forested environments they prefer and may be a challenge to find but they are not quite as fully nocturnal as other owls and do make occasional appearances in the daytime. Wherever they occur, they make themselves known vocally – listening at night is the best way to find one!

Territorial Defense

Barred Owls are fiercely territorial. Males patrol their territories – which range from 270 to 835 acres in the breeding season and expand out to 1,325 to 2,225 acres in the nonbreeding season – nightly by perching on various “sing posts” and issuing their loud, booming eight-hoot song. Territorial hooting is most intense just after sundown and starts up again before dawn when owls are returning to their daytime roosts. It can be heard year-round, but is most intense just before the nesting season in late winter and early spring and again when the season’s young disperse in the fall.

Hunting

Barred Owls navigate their forested territories using a series of corridors – or “flyways” – that they memorize over the years. They are predominantly nocturnal perch hunters, sitting atop trees and turning their heads back and forth, scanning the ground below for signs of movement.

When prey is sighted, they swoop silently down and grab the animals with their feet, sometimes attacking from 20 to 30 feet away. Prey is subdued quickly by the constriction of their powerful talons and is usually eaten whole at the scene. They will devour the heads of large prey items, returning later to finish their meal. Barred Owls will also stash prey at the nest and on branches.

On occasion, Barred Owls hunt on the wing by flying over and scanning the ground below, hovering above potential prey to plan their attack. They have also been observed hunting by “snow plunging,” that is, listening for prey below the snow and dropping down through the icy crust to capture it.

Roosting

During the day, Barred Owls roost in shady, secluded areas within the forest – often at least 16 feet off the ground in tree hollows and near the trunks of dense trees. They can be a challenge to spot, and will usually fly away when disturbed rather than relying on camouflage which makes a close approach difficult. In urban or recreational areas, Barred Owls adapt quickly to human activity and are usually far more tolerant, offering great viewing.

Finding a sleeping Barred Owl on your own may be nearly impossible, but pay attention to the other birds of the area. Crows, woodpeckers, many songbirds, and some mammals like squirrels have learned that Barred Owls feast on their young, so will pester and mob the resting owl by dive-bombing and vocalizing animatedly until it moves on. This raucous scene can expose a flustered Barred Owl.

Barred Owl Predators

As fairly large top avian predators, Barred Owls have few natural predators. By far the biggest threat to them is the Great Horned Owl, which shares the night and much of their range with them. Great Horned Owls are larger and stronger than Barred Owls, making easy meals of eggs, young, and adults alike. Luckily, Great Horned Owls prefer more open areas and Barred Owls can avoid them by staying in densely forested habitats.

On occasions where a Great Horned Owl moves into a Barred Owl’s territory, the Barred Owl will typically relocate.

Other large predatory birds of the forest, like the Northern Goshawk and Cooper’s Hawk, have been known to attack Barred Owls with varying success – in one notable incident a Northern Goshawk attacked a Barred Owl and both birds died as a result. Opportunistic Red-tailed Hawks may also attack a Barred Owl, but this is rare. Barred Owls will also attack each other during territorial disputes.

Raccoons and weasels are known to predate nests, but if caught they are attacked by the ferocious parents. In the south, American alligators will also feed upon grounded fledglings.

Other risks to Barred Owls include hunters, who accidentally shoot the birds in dense vegetation, furbearer traps, and, in urban areas, eating bait-poisoned animals.

Note: Avoid using poisoned bait traps to kill mice and rats. Barred Owls feed on poisoned rodents and the toxins accumulate in their bodies, which can eventually lead to paralysis and death. They also feed the meat to their young which can be lethal to them.

Barred Owl Lifespan

Barred Owls are relatively long-lived, often surviving well into their twenties in the wild. The oldest known wild Barred Owl lived to be over 26 and a half years old. In captivity, Barred Owls can live to be 34 years old.

FAQs

Answer: Barred Owls defend a large territory year-round. If you live in a forested area on the east coast, in the Pacific Northwest, or in Canada, it’s highly likely a Barred Owl has taken up residence in your yard! Males, and occasionally higher-voiced females, will hoot to advertise their presence to rivaling or neighboring Barred Owls, flying from perch to perch marking out the boundaries of their territory.

Barred Owl pairs are highly vocal, and will also hoot to stay in contact with each other and perform hooted duets during courtship.

Answer: Barred Owls find quiet, shaded, and protected spots to roost during the day, often returning to a favorite roost within their territory. Typically, this is at least 16 feet off the ground in a tree hollow or on a branch near the trunk of a dense tree. They are difficult to spot when roosting, and will easily flush if you get too close. Watch crows, songbirds, and squirrels for clues to their whereabouts, as they regularly mob sleeping Barred Owls.

Answer: Barred Owls are true woodland owls and prefer dense, mature forests to live and breed in – but they are quite adaptable! If your yard has several large trees and a water source, you may be able to attract a Barred Owl to take up residence. Adding a large nest box well before the breeding season will also help as Barred Owls typically nest in tree cavities.

Research Citations

Books:

Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

Mikkola, H. (2014). Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide. (2nd Edition). Firefly Books.

Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sibley, D.A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds (2nd Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Online:

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds:

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: