- Osprey Guide (Pandion haliaetus) - June 8, 2022

- American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) Guide - April 28, 2022

The American kestrel is a dapper and spunky little falcon. I view kestrels as the most charismatic of the raptors—these birds are brightly colored, easy to spot, fun to observe, and to top it off, downright adorable.

As such charismatic birds, kestrels have accumulated several affectionate nicknames through the years: “windhover,” “killy hawk,” and “grasshopper hawk,” among others. Each name refers to a different aspect of the kestrel’s lifestyle:

- Windhover: Kestrels can “hover” in place by flying directly into wind currents.

- Killy hawk: The most common kestrel call is a shrill killy-killy-killy!

- Grasshopper hawk: These tiny predators eat correspondingly tiny prey, including grasshoppers.

Despite being the smallest falcon in North America, the American kestrel is often easy to spot and always fun to observe. I often find kestrels hanging out on telephone lines, bobbing their tails up and down before they launch into the wind to track down their next meal.

American Kestrel Taxonomy

The American kestrel (Falco sparverius) is classified in family Falconidae (order Falconiformes) along with falcons and caracaras. Other falcons in North America include the peregrine falcon, prairie falcon, merlin, and gyrfalcon.

Traditionally, kestrels and falcons were considered close relatives of hawks, ospreys, and vultures, since these birds are all diurnal raptors (birds of prey that hunt during the day) and have sharp talons, a fearsome beak, and strong eyesight. However, DNA evidence has confirmed that kestrels are more closely related to songbirds and parrots than hawks. This is an example of “convergent evolution,” where two unrelated groups of animals evolve similar characteristics separately. Keep this in mind if you’re using an older field guide (like a first edition Sibley)—many field guides are organized taxonomically, and older field guides still group falcons and hawks together!

How to Identify American Kestrels

These are the main things to look for when identifying American kestrels:

- Small size: The American kestrel is the smallest diurnal raptor in North America (about the size of a small dove).

- Rusty feathers: American kestrels have reddish-brown plumage, and males have slate-blue wings.

- Shrieking: The most common American kestrel call is the shrill killy-killy-killy!

Appearance

Adult American kestrels are 9–11 inches long and only weigh about a quarter-pound—slightly smaller than your standard pigeon. As with most birds of prey, females are larger and stronger than males, perhaps so they can defend their nests against predators.

Both female and male American kestrels have distinctive rufous plumage (reddish-brown feathers) on their backs and tails, often with black dots or barring (horizontal stripes like a ladder). In contrast, their undersides are buffy or light tan. American kestrels also have two vertical black stripes on their face—a “mustache” and “sideburns”—lending them a rather dapper expression.

American kestrel plumage is sexually dimorphic, meaning that males and females have different feather colorations. Female kestrels have rufous wings that match their backs and tails, whereas males have contrasting blue-gray wings. In addition, the tails of male kestrels are redder than females’, with a black band along the end.

Although American kestrels have a similar body and wing shape to other falcons, they are easy to distinguish based on their small size and reddish-brown coloration. The Eurasian kestrel (rarely observed in North America) is most similar to the American kestrel but is larger and less vibrantly colored. Eurasian kestrels also have a single vertical stripe on the face instead of two.

Movements

Like other falcons, American kestrels fly with their wings bent back at the wrist. The narrow, angular wings of falcons are distinct from hawks, which have a much broader, flatter wing shape. I often think that falcons look like fighter jets, whereas hawks look more like cargo planes!

American kestrels are often observed “wind hovering” or “kiting”: flying directly into the wind and countering windspeed so they remain in the same spot. This behavior isn’t technically hovering since it requires wind as a counter-current (hummingbirds are the only birds that can truly hover without the aid of wind) but does allow kestrels to remain in one spot while looking for prey. As they hover, they keep their head exactly still while flapping their wings and manipulating their tails against the wind.

Since hovering takes a lot of work, kestrels often look for exposed perches to sit on instead. From the vantage point of a tree branch or telephone line, they can look for prey without constantly flying. Kestrels pump their tails up and down when perched, likely to maintain balance.

Vocalization

The American kestrel’s nickname “killy hawk” is a reference to the bird’s shrill call. When stressed, alarmed, or even just excited, kestrels call out killy-killy-killy, or a more slurred klee-klee-klee. Kestrels also use two other types of call: a whine call lasting up to two minutes that is used during courtship or copulation, and a chitter call used during interactions between individuals.

American Kestrel Distribution

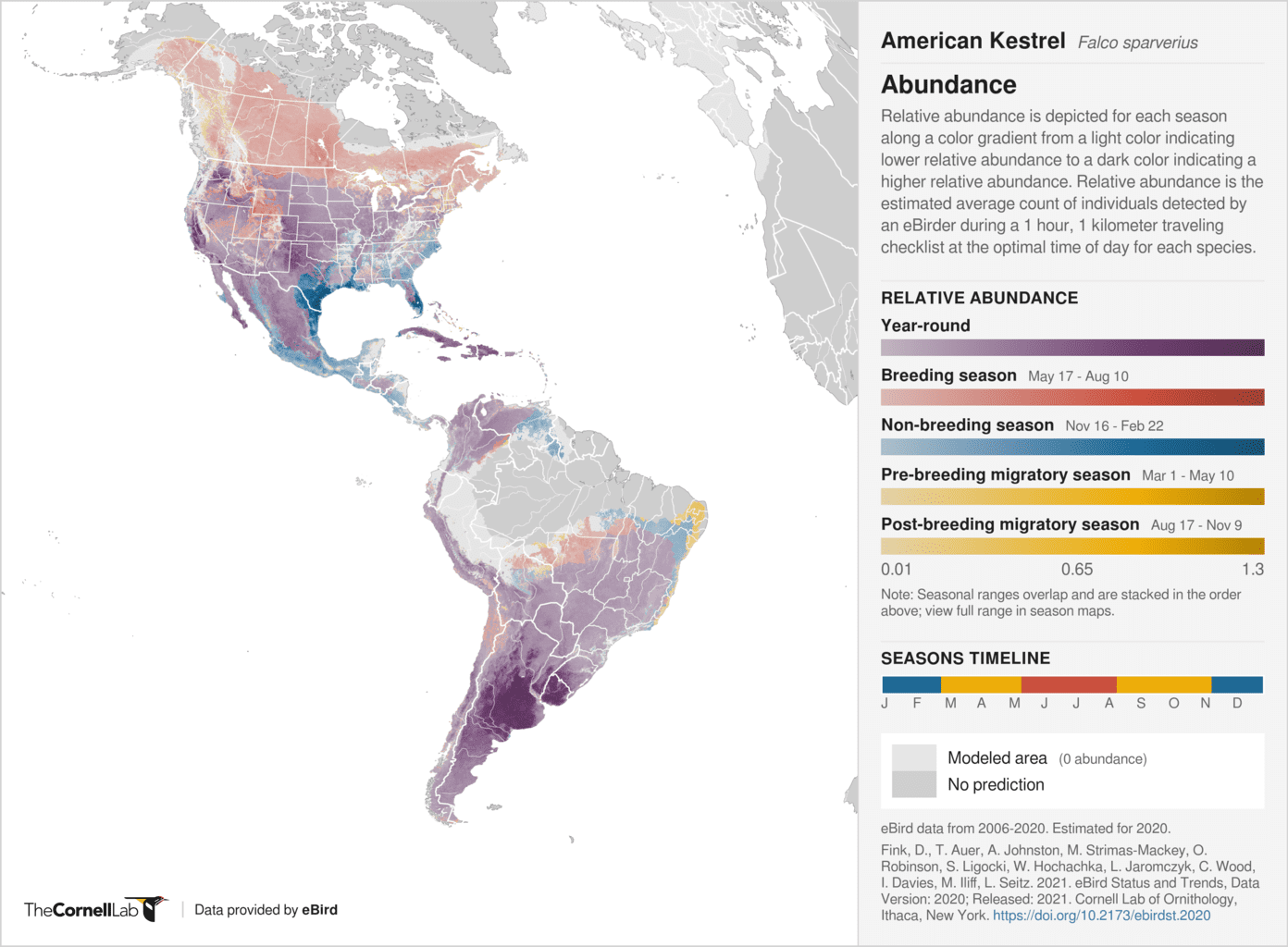

American kestrels are widespread throughout North and South America, excluding arctic regions of Canada and most of the Amazon rainforest. Over the past several decades, citizen scientists have recorded over 2.7 million sightings of American kestrels with eBird.

Several other kestrel species exist elsewhere in the world, but these species’ ranges do not overlap with the American kestrel. Rarely, Eurasian kestrels will be blown off course in a storm, leading to accidental observations along the east and west coasts of North America.

Habitat

American kestrels thrive in a variety of climates and habitat types, from alpine meadows to deserts and shrublands. Their main habitat requirement is visibility—kestrels prefer open spaces with limited or low-growing vegetation. Open space is critical since kestrels are visual hunters and rely on a wide, unobstructed view to spot prey from above. Kestrels can readily adapt to urban and agricultural areas since these are often open spaces.

Migration

Some American kestrels are non-migratory residents, but others fly long distances between their breeding and overwintering grounds. In North America, a kestrels’ tendency to migrate depends on where they breed; northern breeding populations tend to migrate farther distances, while southern populations are completely sedentary.

Population Status

American kestrel numbers are relatively stable throughout their range although some populations are declining, particularly in the northeast United States. Population decline might be related to the decreased survival of overwintering kestrels, as well as habitat loss and lack of suitable nesting spots.

The American kestrel is not federally protected by the Endangered Species Act, and its conservation priority is listed as “least concern” by the IUCN Red List. However, American kestrels are protected under the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, and certain subspecies are listed as threatened or endangered by state laws, such as in Delaware and Florida.

American Kestrel Life History

As a diurnal raptor (a bird of prey that hunts during the day), the American kestrel shares many traits and habits with falcons and hawks.

Diet

American kestrels are carnivores, but their tiny size limits them to hunting small animals. Since males are smaller than females, they usually hunt for smaller prey items. This size allocation can be helpful when prey is scarce, since males and females can hunt from different prey populations.

Beyond the size restriction, kestrels aren’t picky eaters; they eat everything from rodents and reptiles to insects and amphibians. Kestrel diet varies with the time of year, depending on which prey species are most abundant. For many populations, voles are an especially important food source.

Although American kestrels aren’t picky about the types of prey they capture, they are picky about which parts they dine on. Kestrels often pick through their meal and eat the soft juicy muscles and organs, avoiding intestines and skin (unless food is scarce and the kestrel is hungry). Like other birds of prey, kestrels can’t digest parts like bones, teeth, and fur. These elements collect in the bird’s crop, where they form a pellet that is regurgitated about a day later.

Hunting Behavior

American kestrels are “sit-and-wait” predators who hang out on a perch until they spot their prey from above. If a perch isn’t available, they may instead opt to hover and wait, maintaining their location by flying directly into the wind.

Once a potential meal has been spotted, kestrels often bob their head to help estimate distance before zooming down and attacking by surprise. Kestrels usually kill their prey by biting the head and neck, often severing the spinal column.

To find fruitful (or vole-ful) hunting grounds, kestrels have a special power: their ability to see pee. Like most other diurnal bird species, kestrels can see ultraviolet wavelengths of light. Small rodents such as voles mark their trails with urine streams that reflect ultraviolet light, so kestrels may be able to locate prey by looking for areas with bright (and therefore fresh) urine trails. Although this behavior is not confirmed, research suggests that some kestrel species favor hunting areas with fresh urine.

Individual American kestrels can become specialists for certain types of prey, perfecting the art of a particular hunting technique. Some kestrels specialize in chasing and capturing birds and bats in midflight, and others even become moth specialists, hanging out in sports stadiums to catch the bugs attracted to the stadium lights!

Breeding and Nesting

American kestrels are monogamous throughout each breeding season, and often remain in pairs across multiple breeding seasons. During courtship, a male lead a female to potential nest sites and brings her gifts of food. Pairs bond by flying in aerial displays of dives and flutters, with the male enthusiastically calling killy-killy-killy.

Kestrels rely on already existing holes for nesting, such as tree cavities, abandoned woodpecker hollows, crevices in buildings, or nest boxes. Kestrel nests are simple and messy; parents don’t add any bedding, and nestlings haphazardly defecate on the walls. Even so, breeding kestrels often return to the same nesting spot year after year.

American kestrel eggs are yellowish to light brown and mottled or speckled, and roughly the same size and shape as a small chicken egg. Kestrels lay four or five eggs at a time and incubate the eggs for about a month. Upon hatching, kestrel nestlings are feeble and helpless; they have barely any feathers and their eyes are closed, although they can beg for food within a day of hatching.

Both parents bring food to the nestlings, feeding the loudest chick first. At first, parents dismember prey into an appropriate size and gently place each bite into a chick’s beak. When the chicks are strong enough, the parents leave entire carcasses for the chicks to dismember themselves. The chicks grow quickly; after a month, the nestlings fledge and leave the nest, but stay nearby and continue begging for food. They are reliant on their parents for another two weeks before they can consistently feed themselves.

Predators

Despite their fierce persona, American kestrels often end up as meals for other predators. Larger raptors such as Cooper’s hawks, sharp-shinned hawks, and great horned owls often prey upon kestrels. Nesting birds are particularly vulnerable; many species including rat snakes, raccoons, squirrels, crows, and fire ants will attack kestrel nests and eat the eggs and chicks.

Humans also pose many threats to these tiny raptors, through trapping, hunting, roadkill, predation by dogs and cats, window collision, power line electrocution, and building entrapment.

Lifespan

Life is difficult for a young American kestrel in the wild, and many perish from starvation during their first winter. Only half of juvenile kestrels survive to adulthood, and those that survive their first winter are only expected to live up to three years. Occasional individuals will live for longer than a decade, including one banded kestrel in Utah who was recaptured after 14 years.

The average lifespan for captive American kestrels is around five years. The oldest captive kestrel, a mealworm-loving falconry bird named Horus, lived to the ripe old age of 19.

American Kestrel FAQ

Answer: An adult American kestrel is smaller than a pigeon…but much better equipped for battle! Despite their size disadvantage, kestrels have been observed attacking and eating prey items larger than themselves, including pigeons, woodpeckers, and squirrels.

However, kestrels are much more likely to pursue smaller and easier prey items, such as insects or rodents.

Answer: With a large investment of time, money, and dedication, you could consider taking up falconry. American kestrels are one of the raptor species allowed for falconry in the United States, although regulations very by state.

Falconry is more of a lifestyle than a sport. Falconers develop a tight relationship with their birds, training them to hunt and return with prey. This relationship takes years of preparation and practice, and falconers need to interact with their birds daily.

Answer: If you find a sick or injured American kestrel, you should contact your local wildlife rescue center immediately. You can visit Animal Help Now to locate an animal rescue near you.

In the meantime, attempt to transfer the kestrel to a container with a lid. You can use a towel to scoop up the bird—just make sure its head is covered and wings are tucked naturally. If the bird is too active to handle, you may need to set a box over the bird and leave it in place while contacting an animal rescue expert.

Once the kestrel is contained, keep it in a warm, dark, and quiet place. Do not attempt to give the bird food or water. Keep curious pets and children away—remember that this is a bird of prey, with sharp weapons on its feet and hands!

References

Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2019). All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/American_Kestrel

Dunn, L., J. Alderfer, P. Lehman, M. Dicknson. (2002). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America, fourth edition. National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C., USA.

Sibley, D. A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds, second edition. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, USA.

Smallwood, J. A. and D. M. Bird (2020). American Kestrel (Falco sparverius), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.amekes.01Sibley

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: