- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

Petite and adorable Northern Saw-whet Owls are common but seldom seen due to their elusive, nocturnal habits and preference for living in dense forests. Spend some time in the woods during the summer, and you’ll likely hear one, though!

My experiences with Northern Saw-whet Owls relate to my times spent in the spring forests of the Pacific Northwest, hearing their nonstop, monotone whistles all night through an open window issuing from the deep woods outside.

The Northern Saw-whet Owl came to national attention in the winter of 2020 when a dehydrated, starving female owl was found trapped in the boughs of the annual Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree at its unveiling – accidentally transported 170 miles with the felled spruce. The owl, named Rocky, was successfully rehabilitated and released and will now serve as the tail décor for the Frontier Airlines fleet.

Keep reading to learn how to identify, locate, observe, and help these tiny but mighty nocturnal predators of the forest!

Taxonomy

Northern Saw-whet Owls are members of the order Strigiformes, which contains all of the world’s owls in its two families: Tytonidae and Strigidae. Northern Saw-whet Owls are members of the family Strigidae, known as the “true owls” or “typical owls,” which includes 230 species in its 24 genera.

The Northern Saw-whet Owl is one of five species in the genus Aegolius – ancient Greek for “bird of ill omen” – which are also called “forest owls” due to their preferred woodland habitats. Aegolius owls are small-bodied with short tails, large heads, and massive facial disks. They occur throughout the temperate and cold forests of Eurasia, the Alps, and the Americas.

The Northern Saw-whet Owl was first described by the Canadian missionary and naturalist John Henry Keen in 1896 during his explorations of the Canadian forests. Its common name was inspired by the species’ vocalizations, which reminded settlers of a saw being sharpened on a whetstone.

Taxonomy at a Glance

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Aves

Order: Strigiformes

Family: Strigidae

Genus: Aegolius

Species: Aegolius acadicus

How to Identify the Northern Saw-Whet Owl

If you’re in the forests of northern North America or the mountains of Mexico in summer or anywhere in the United States with dense conifer stands in winter, keep your eyes peeled for the Northern Saw-whet Owl – the smallest nocturnal owl of northern woodlands.

Adults

Northern Saw-whet Owls are small – about the size of an American Robin – with relatively large heads and short tails. They have pronounced rectangular facial disks that appear to take up half of their bodies and piercing yellow-orange eyes surrounded by black “eyeliner.” They have light, cream-colored feathering on their toes, resulting in sharp tan claws with black tips.

To distinguish them from other small woodland owls, look for the distinctive V-shaped white marking on their foreheads, the black spots between their bill and each eye, and their lack of ear tufts. Their dark bills are surrounded by dense bristles, which scientists believe are used to sense objects at close range.

Adult Northern Saw-whet Owls have cryptic plumage that allows them to camouflage well in their forest environments. They have dark, reddish-brown plumage on their backs, on the tops of their tails, and on their heads with lighter cream-colored to buffy undersides. Thick, vertical brown stripes mark their pale chests, and their foreheads and crowns are heavily streaked with white and gray lines. They also have prominent white spots on their otherwise dark “shoulders.”

For their size, Northern Saw-whet Owls have relatively long wings, giving them a wingspan of 17 inches. They stand about eight inches tall when perched. Males and females look identical, but females are slightly larger. This size difference is most pronounced during breeding season when females weigh significantly more than their male counterparts.

Subspecies

There are two subspecies of the Northern Saw-whet Owl. The Aegolius acadicus acadicus subspecies is the most common, occurring from southern Alaska to central Mexico.

The subspecies A. acadicus brooksi is only found on the Haida Gwaii archipelago off the coast of western British Columbia. This subspecies is darker overall, with a tan-colored wash over its lighter parts and with white eyebrows only rather than a full V-marking on the face. These owls are often called “Queen Charlotte Owls” after Queen Charlotte Island, part of their native archipelago.

Taxonomists have proposed designating this population as a new species called the Haida Gwaii Saw-whet Owl, but genetically they are not yet distinct from the rest of the species. There are also semi-isolated populations of Northern Saw-whet Owls on the Allegheny Plateau and in the southern Appalachian Mountains of the United States that may one day become their own species.

Immature Birds

Nestling Northern Saw-whet Owls are covered in a coat of sparse white fuzzy down when they first hatch. At two to four weeks old, they begin growing a set of fluffy feathers that is completely unlike the plumage of an adult.

Juvenile owls with their first set of plumage are most commonly encountered between May and September. They look quite different from adults. Their backs and heads are uniformly dark reddish-brown without white markings, while their chests are a light cinnamon to buffy color, lacking the characteristic vertical brown streaks of the adult. They do not yet have the fully developed white V-marking on their faces instead of having a faint X between their eyes.

Similar Species

The Northern Saw-whet Owl shares much of its range with the Northern Pygmy-Owl but can be distinguished by its shorter tail, bigger head, and more pronounced facial disk. Northern Pygmy Owls are also diurnal and therefore only active during the day. If you encounter a small sleeping owl in the woods during the day, it is most likely a Northern Saw-whet Owl.

The Boreal Owl (also called Tengmalm’s Owl) is a cousin species also of the genus Aegolius. Its range overlaps with the North Saw-whet Owl in northern Canada, Alaska, and parts of the mountain west. Boreal Owls are larger, have white-spotted heads, have a black border around their facial disks, have pale bills, and only have white eyebrows.

The Short-eared Owl has a large range that overlaps with the Northern Saw-whet Owls in many places, but they look quite different. Short-eared Owls are significantly larger, have white eyebrows only, and have small ear tufts.

The Unspotted Saw-whet Owl may occur in Mexico alongside the Northern Saw-whet Owl. As their name suggests, Unspotted Saw-whet Owls lack the white markings on the back and head that Northern Saw-whet Owls have. They also have pale, unstreaked chests.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Vocalizations and Sounds

You are far more likely to hear a Northern Saw-whet Owl than see one. In fact, the species’ common name derives from its vocalizations, which reminded settlers of a saw being sharpened on a whetstone – although no one is quite sure which exact vocalization inspired the name! Listen for their seemingly endless high-pitched hoot series in forests late at night between January and June.

Territorial Hooting

Male Northern Saw-whet Owls issue a nonstop series of high-pitched, monotonous, whistle-like hoots – that sound like “toot-toot-toot-toot” – as their song to attract mates and signal their territory to other male Saw-whet Owls.

This two-hoot-per-second series is constantly repeated on a regular rhythm at the same pitch for hours, often without breaks. This tendency of the Northern Saw-whet Owl even inspired a lyric in the Grateful Dead song “Unbroken Chain” – “song of the saw-whet owl out on the mountain, it’ll drive you insane.” It might not drive you insane, but it’s certainly noticeable! Hoots are audible up to one-half of a mile away, resonating through the dense forest.

Listen to the male Northern Saw-whet Owl’s hoot series in this video:

Rival males answer another male’s hoot series by issuing their faster, softer, and lower-pitched version. Females will also produce a series of hoots in response to a male suitor during courtship. While they are most frequently heard early in the breeding season, Northern Saw-whet Owls vocalize year-round.

Other Sounds

Northern Saw-whet Owls have at least eleven known vocalizations. In addition to their signature hoot series, they will issue an ascending whine that sounds like a crying cat, a barking “kew,” a high-pitched “tsst!” sound, an aggressive, scraping “screev,” and numerous other whistles, barks, squeaks, guttural noises, and twittering calls.

Juveniles produce a repetitive, raspy shriek, and owls of all ages will clack their bills when approached or threatened. The brooksi subspecies also have a few additional vocalizations unique to their population.

Where Does the Northern Saw-whet Owl Live?

The Northern Saw-whet Owl has a reasonably extensive range across the forests of northern North America, the mountains of the interior west and Mexico, and the temperate coastal woodlands. They are very adaptable and tolerate cold environments better than many other bird species.

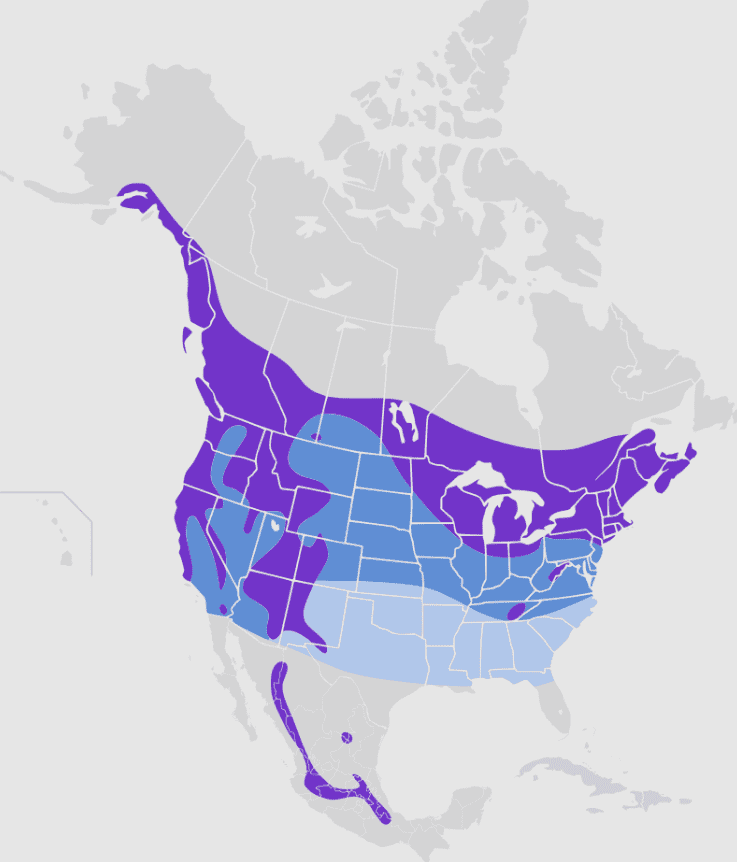

Range

Northern Saw-whet Owls can be found in southern Alaska, throughout southern Canada, and south to southwest Mexico. Their breeding range is farther north than that of most other bird species, extending across the northern forests of Canada, the Pacific Northwest, coastal California, and the northeastern-most United States to the mountains of the interior United States and central Mexico.

In winter, these owls can be found across the United States in any habitat with dense vegetation, especially stands of conifers.

Habitat

For breeding, Northern Saw-whet Owls prefer extensive mature or mixed forests with open understories near a water source and with suitable nesting sites. They are most commonly found in boreal forests, dense coniferous forests, open pine forests, spruce-fir forests, cedar swamps, spruce-poplar forests, oak woodlands, pine-oak forests, tamarack bogs, humid forest edges, and riverside or riparian forests.

If nest boxes are offered, they will also breed in less desirable habitats like coastal scrub, poplar plantations, and sand dune meadows. In fall and winter, some Northern Saw-whet Owls will move into deciduous forests, disturbed woodlands, savannahs, shrub-steppe habitats, and anywhere with a grove of conifers nearby.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Migration

Many Northern Saw-whet Owls are year-round residents in their preferred temperate forest habitats. Some migrate south from the extreme north or move downslope from higher mountain elevations to find prey during the winter. Every four winters or so, Northern Saw-whet Owls experience an irruption, in which many owls suddenly move south in search of prey.

When migrating, Northern Saw-whet Owls fly at night, following known routes across the land. They are also capable of crossing large bodies of water, like the Great Lakes, and one owl even turned up on a fishing boat 70 miles off the coast of New York.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Diet and Feeding

Northern Saw-whet Owls prefer to feed on small mammals, especially rodents, but they will take other prey when the situation arises.

Rodents

Rodents make up about 85% to 99% of the Northern Saw-whet Owl’s diet. They feed primarily on deer mice but will also take white-footed mice, harvest mice, jumping mice, house mice, and pocket mice. Voles are another favorite, with red-backed voles, montane voles, meadow voles, red tree voles, and heather voles all regularly taken.

Other Animals

Northern Saw-whet Owls will also feed on other small mammals like shrews, bats, chipmunks, shrew-moles, the young of pocket gophers, flying squirrels, and red squirrels.

Birds are taken less often, typically during migration. Small songbirds like chickadees, titmice, swallows, wrens, warblers, sparrows, juncos, kinglets, robins, and other thrushes are preferred, but birds as large as Rock Doves and other small owl species have been successfully captured.

On occasion, Northern Saw-whet Owls will feed on large insects – like moths, grasshoppers, beetles–and frogs. Coastal populations will also take intertidal crustaceans, amphipods, and isopods.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Breeding

The Northern Saw-whet Owl breeding season occurs between mid-March and mid-April, depending on location, and extends through late June.

Courtship

Migratory male Northern Saw-whet Owls arrive on the breeding grounds before females and begin proclaiming their territories and advertising to females with their hours-long hoot series as early as late January.

An interested female will answer his series with a high-pitched “tsst!” call or will respond with a whistled series of her own. The male will then perform an aerial courtship display, in which he circles a perched female up to 20 times before landing and offering her a prey item. He will continue to bring her prey items throughout the courtship, providing extra nourishment as she prepares for the nutritionally expensive task of egg-laying.

Most pairs are monogamous, at least within the breeding season, but Northern Saw-whet Owls go their separate ways and mate with different partners once the young are fledged. In years when prey is exceedingly abundant, some males may have multiple mates and families. Females typically leave once the young are of a certain age and often raise a second brood with a different partner.

Nesting

Males search for potential nest sites within their territories early in the breeding season. Woodpecker holes, typically those created by Pileated Woodpeckers and Northern Flickers in snags, are favorites. Still, other natural tree cavities and nest boxes eight to 44 feet off the ground with two to three-inch entrance holes are also used.

Once a good site is located, the male issues his hooted series nearby to draw the female’s attention to it. Ultimately, the female chooses the final nest location. Like most owls, Northern Saw-whet Owls do not construct their own nests. They use whatever wood chips, old animal bones, grass, hair, feathers, fur, or other lining is already present in the secondhand nest hole. Nest sites are seldom re-used year to year.

Eggs

Female Northern Saw-whet Owls lay between three and nine eggs, with five to six eggs being the most common clutch size. She lays the eggs at one-to-three-day intervals but begins incubating after laying the second egg, so the young are always different ages. The eggs are white, elliptical, and smooth but not glossy.

Once she lays the first egg, the female doesn’t leave the nest cavity. She incubates the eggs by herself for 26 to 34 days while the male brings her food, often storing extra prey items in the nest.

Nestlings

The young hatch several days apart, so they vary in age and size. They are altricial – mostly naked and helpless with eyes closed – and sparsely covered in white down when they first emerge from their eggs.

The female continues to brood the young for three weeks while the male hunts nonstop. She is a diligent mother, tearing the prey items into smaller pieces and offering them to the owlets while keeping the nest clean of feces, pellets, and leftover animal parts.

The owlets’ eyes open when they are eight to nine days old. As nestlings, they have brown irises. Their white baby down is replaced by fluffy feathers when they are just two to four weeks old. The oldest owlets leave the nest at 10 to 14 days of age but stay perched close by for several more weeks, receiving food from their father.

The female leaves the nest when the youngest owlet is 18 days old and beginning to get feathers. She may join the male in hunting and feeding the young or depart completely and roost elsewhere. Sometimes, she finds a new mate and raises a second family! In her absence, the nest quickly becomes soiled. This may be the reason nest holes aren’t re-used year to year.

The male continues to feed the young (often by himself) for several more weeks. Older owlets may help him by feeding prey to their younger siblings. The young owlets fledge when they are just four to five weeks old, dispersing to find their own territories.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Population

Although they are elusive and rarely seen, Northern Saw-whet Owls are widespread throughout their range and are among the most common owls of North American forests. Partners in Flight currently estimates a global breeding population of two million owls.

However, this may not always be the case. Because they prefer large wooded areas, they will likely experience population declines across their range in the coming years as forests are cleared due to logging and urbanization.

Is the Northern Saw-whet Owl Endangered?

Currently, the Northern Saw-whet Owl is not endangered. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists the species as having a status of Least Concern, meaning it is not at immediate risk for extinction. However, habitat loss has caused their numbers to decline in some areas in recent years.

North Dakota and South Carolina have designated the Northern Saw-whet Owl as a species of special concern due to the widespread removal of forests. The brooksi subspecies of British Columbia’s Haida Gwaii islands are listed as threatened.

Northern Saw-whet Owls show a strong preference for large, mature forests that can support their rodent prey populations and provide nest sites. Since development and logging practices only increase, deforestation will eventually spell doom for these small woodland owls.

Simple alterations like leaving dead trees standing after clear-cutting to provide nest sites and hanging nest boxes have helped the species in deforested areas. But the long-term effects of climate change will likely reduce their woodland habitat further in the coming decades, especially in the southern parts of their range.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Habits

Northern Saw-whet Owls are entirely nocturnal, emerging from their daytime roosts to hunt and proclaim their territories at dusk. The best way to find one is to listen for their repetitive hooting on a quiet night in a forest near you. You can also search for a roosting owl during the day, but this is more challenging!

Territorial Defense

Male Northern Saw-whet Owls are only fiercely territorial in the breeding season, extending from late January to late June. They fly to different locations within their territories, issuing their characteristic series of monotone hoots. They will also hoot when scouting for nest sites has been successful.

Hooting is most intense early in the season when males must re-define their existing territories (if residential) and establish new ones (if migratory) while also attracting a mate. Typically, hooted warnings deter rival males, but sometimes an intruder must be physically battled.

Late in the breeding season, when males are busy hunting to feed their families, things quiet down again. Outside the breeding season, males and females lead solitary lives. Northern Saw-whet Owls may call off and on in the fall and winter but far less frequently.

Hunting

Northern Saw-whet Owls are efficient nocturnal perch hunters, sitting quietly and perfectly camouflaged in a tree, scanning the forest floor for small sounds or signs of movement. They have excellent low-light vision, like most owls, and hunt by both sight and sound.

Like Barn Owls, Northern Saw-whet Owls have asymmetrical ear openings – one points up, and one points down – which allows them to hear in the vertical dimension. This superb sense of hearing enables them to hunt in total darkness and will enable them to accurately capture prey under thick leaf litter or snow.

When they have a lock on an animal below, they swoop down silently – owing to their modified fringed flight feathers – and snatch the prey with their powerful talons. They often eat half of their kill at capture and save the second half for a later meal.

Roosting

At dawn, Northern Saw-whet Owls return to a preferred roost in a thickly-vegetated location to sleep. Coniferous trees are a favorite, and they either roost very close to the trunk or at the densely foliated outer tips of branches about eleven feet off the ground.

Sleeping Northern Saw-whet Owls hold themselves very still, close their eyes, and rely on their cryptic plumage to keep them concealed. They are easily approached while roosting, and you can get very close to one before they fly away. Try to avoid flushing one, as this exposes it to predatory diurnal raptors. You will often be standing next to one barely above eye level and not even know it.

Check out this footage of a roosting Northern Saw-whet Owl:

The easiest way to find a roosting Northern Saw-whet Owl is to watch the other birds of the forest for clues that a predator is nearby. Mixed flocks of songbirds are better at seeing owls than we are and will create a ruckus of calls and flapping while mobbing a resting owl.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Predators

Due to their small body size, Northern Saw-whet Owls are prey just as often as they are predators.

Other large carnivorous birds of the forest pose the greatest threat. Northern Goshawks and Cooper’s Hawks are both accomplished woodland bird eaters, as are Broad-winged Hawks and Peregrine Falcons. Luckily, these species are diurnal, so saw-whet owls are safe so long as they remain hidden while roosting.

At night, the biggest danger comes from larger forest-dwelling owls. Great Horned Owls, Eastern Screech Owls, Long-eared Owls, Spotted Owls, and Barred Owls have all been known to kill their much smaller cousins.

Northern Saw-whet Owls also compete for limited nest sites with other cavity-nesters, like the Boreal Owl, European Starling, and various species of squirrels. Eggs and young are at risk if one of these more aggressive creatures lays claim to a nest hole. Few other predators can reach their inaccessible nests. Still, the marten, a forest mammal adept at climbing, and the insightful jays, ravens, and crows may occasionally prey on eggs and young.

Other threats include logging, in which active nest trees are felled, and the use of rodenticide poisons, which either remove their preferred prey or renders it toxic.

Note: Avoid using poisoned bait traps to kill mice and rats. Northern Saw-whet Owls feed on poisoned rodents, and the toxins accumulate in their bodies, eventually leading to paralysis and death. They also provide meat to their young, which can be lethal to them.

Northern Saw-Whet Owl Lifespan

As with all owl species, mortality is very high in a fledgling’s first year of life. Young owls must learn how to successfully hunt, migrate, stake out territories, and avoid being captured by predatory birds. If they survive to adulthood, they may live fairly long lives for a small bird – the oldest wild Northern Saw-whet Owl lived to be at least nine years and five months old. In captivity, they can live up to 16 years.

FAQs

Answer: Due to their small size and elusive nature, Northern Saw-whet Owls were once believed to be very rare. But at the time, not much was known about the species. With modern banding practices, ornithologists are learning more about bird populations and migrations each year. As a result, scientists have discovered that these birds are quite common in their preferred habitat throughout their range. They are simply extremely hard to see in the dense forest!

Answer: The Northern Saw-whet Owl’s common name comes from the species’ vocalizations, which reminded early settlers of a saw being sharpened on a whetstone. It is unclear which exact vocalization inspired this name, as they have several different calls! It is most likely the male’s repetitive series of monotone hoots that goes on for hours – much like regularly repeated drags across a whetstone – but it could also have come from the raspy, grating “screev!” call that definitely gives the impression of metal being scraped on stone.

Answer: Northern Saw-whet Owls require large forested areas to hunt their favorite rodent prey, but they are quite adaptable and will move into other habitats so long as suitable nest and roost sites are available. If you live near a shrubby or forested area within their breeding range, hang a nest box up before January. Also, ensure you have some dense vegetation on your property or nearby to provide roosting sites. You just might succeed in attracting a Northern Saw-whet Owl pair!

Answer: While they are indeed small and adorable, you cannot keep a Northern Saw-whet Owl as a pet. For one, it is illegal under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and can incur a $15,000 fine and up to six months in prison. Special permits are granted, but only for the purposes of rehabilitation, education, and falconry – all of which are highly regulated.

Additionally, owls are wild animals and simply do not make good pets. They are difficult to care for – requiring live prey, ample space, and frequent gross clean-up – and have sharp bills and talons that can inflict damage if mishandled. Unlike most birds kept as pets, which are social by nature, owls are mostly solitary animals with no interest in being touched, handled, or interacted with.

Research Citations

Books:

Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

Mikkola, H. (2014). Owls of the World: A Photographic Guide. (2nd Edition). Firefly Books.

Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Sibley, D.A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds (2nd Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Online:

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology: All About Birds:

NBC News (Rocky’s Story):

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: