- Best Amazon Bird Baths Guide - September 26, 2023

- Best Copper Bird Baths - August 30, 2023

- Best Bird Baths Available at Home Depot - August 26, 2023

Introduction

Tap-tap-tap…tap-tap-tap…if you’re anything like me, the unmistakable sound of a woodpecker instantly draws your attention. I’ll fully admit I’m a visual birder, not an auditory one: I’m much better at identifying birds by their appearance instead of their sound.

That means I’ll never be able to tell some species apart (the dreaded flycatchers come to mind), but I’m very cued into an individual’s colors and behaviors instead.

Woodpeckers come in many shapes and sizes and have a diversity of feeding strategies and habitats, but there’s one thing that they all do: drill into wood to make cavities.

Various other species subsequently use these nesting cavities, so woodpeckers are essential in providing homes for other wildlife. It also means that you can find woodpeckers by listening for the repeated taps that show they are excavating cavities or drilling for food.

All woodpeckers are within the Family Picidae, but this includes two other groups of birds (wrynecks and piculets). To get to true woodpeckers, we need to go one taxonomic unit lower to Subfamily Picinae.

There are about 240 species of woodpeckers in this subfamily. Luckily for birdwatchers, within North America, only some of those are black and white, and only a handful of the black and white ones fall into the category of ‘lookalike’ that requires a bit of extra attention to tell apart.

Especially during North America’s winter, you are likely to see one or two species of black and white woodpeckers on your backyard feeder. The hairy and downy woodpeckers are so common that sometimes birdwatchers can be forgiven for forgetting that woodpeckers come in other colors!

Bottom line up front

Black and white woodpeckers have similarities in coloration but little else. They are not clumped into one genus, so their similar colors are not from a shared evolutionary history.

They are different sizes, with different migratory patterns, and occupy different habitats. There’s nothing linking them except that they all have evolved some variation of using black and white in their feathers – and they don’t even do that the same way!

Taxonomy

Woodpeckers are classified as follows:

- Kingdom Animalia

- Phylum Chordata

- Class Aves

- Order Piciformes

- Infraorder Picides

- Family Picidae

- Subfamily Picinae

All true woodpeckers are in the Subfamily Picinae. Within that, there are five tribes of woodpeckers. The four genera that contain North American black and white woodpeckers are all found in Tribe Melanerpini, along with the one genus (Sphyrapicus) of black and white sapsuckers, with one exception – the Ivory-billed woodpecker – located in the Tribe Campephilini.

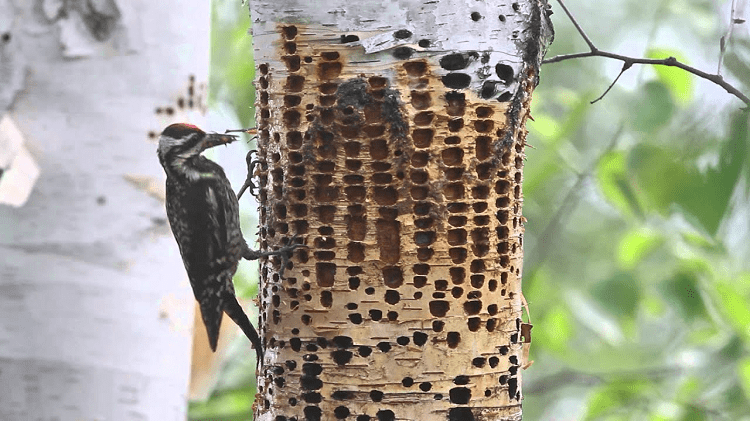

All the sapsuckers have dashes of yellow on their breast or belly, and all are migratory to some extent because they rely on sap (as their name suggests). They tend to drill a series of holes in a line, feeding on the sap and the insects attracted to it.

Genus Picoides

- Downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) – most of the US and the southern half of Canada up to Alaska

- American three-toed woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis) – midwest US, the southern half of Canada up to Alaska

- Black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) – southern Canada, scattered in western states

- Nuttall’s woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii) – California

- White-headed woodpecker (Picoides albolarvatus) – Mountain pine forests of western US states

Genus Leuconotopicus

- Hairy woodpecker (Leuconotopicus villosus) – most of the US and the southern half of Canada up to Alaska

- Red-cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis) – the southern part of SE states

Genus Melanerpes

- Red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) – the eastern half of the US and southernmost parts of Canada

- Golden-fronted woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons) – Texas, SW Oklahoma, and eastern Mexico

- Red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) – eastern half of the US, very southern Ontario

- Acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus) – west coast of the US and Arizona/New Mexico down to Mexico

- Gila woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis) – Arizona, extreme SE California, and Baja California and western Mexico

Genus Dryobates

- Ladder-backed woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris) – southern portion of west and central US, Mexico

- Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) – all of the southeast US, southern Ontario, northwestern corner of the US

Genus Campephilus

- Ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) – southeast US, Cuba

Genus Sphyrapicus

- Yellow-bellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius) – middle Canada in the west through to southern Canada in the east, central and southern US, and Mexico (winter)

- Red-naped sapsucker (Sphyrapicus nuchalis) – west-central states of the US, SE British Columbia, Mexico (winter)

- Red-breasted sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber) – western coast of the US

- Williamson’s sapsucker (Sphyrapicus thyroideus) – coniferous forests scattered throughout western US states, Mexico (winter)

Let’s delve into each species of woodpecker. Instead of talking about them according to taxonomy – they’re not always closely related! – I’ve grouped lookalike species because we’re bird watchers, and I’ve identified what colors or patterns are unique to each one.

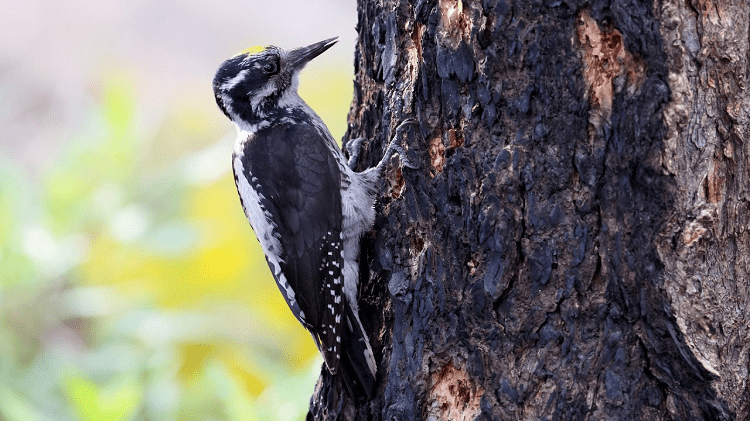

The lookalike Woodpeckers: Downy woodpecker (Picoides pubescens) and Hairy woodpecker (Leuconotopicus villosus)

If you do any birding in North America, you will likely encounter one or both of these species. These two tend to be the most confusing of the black and white woodpeckers, and even experts need to take a moment to get them right. Their ranges overlap entirely, so you’ll have to rely on visual cues to tell them apart. Both have a:

- black crown

- black eye stripe and mustache

- white stripe down their back bordered by black

- white-spotted wings

- white throat and belly

- tail with black central feathers and white outer ones.

Their differences are:

- body size – hairy woodpeckers are larger than downy woodpeckers

- bill size – the bill of a hairy is as long as its head, while the bill of a downy is 1/3 the length of its head

- tail feathers – hairy woodpeckers have pure white outer tail feathers, while downy woodpecker tail feathers have black spots

The combination of spotted wings, white back, and white belly will distinguish these two species from any other black and white woodpecker.

These two are the most northern-ranging woodpeckers in Canada, which may be partially due to their generalist habitat requirements, occupying many types of forests and woodlots. They also readily come to backyard feeders. The downy woodpecker is the smallest in North America.

The woodpeckers with only Three Toes: American three-toed woodpecker (Picoides dorsalis) and Black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus)

Most woodpeckers have four toes, but these two species only have three. That’s not likely to help you identify them, as the inner toe is missing and so not very obvious.

This adaptation allows both species to lean farther back and impart a more powerful blow while drilling into trees. These two species also have nearly identical ranges, preferring the boreal forests of much of Canada and portions of the western US. These are also the only two black and white species to have a splash of yellow on the crown in males (and juveniles) – there is no color on adult females.

These two lookalikes are not backyard birds, but anyone adventuring into a coniferous forest may encounter them. To tell them apart from other black and white woodpeckers, look for finely barred flanks and minimally spotted wings. To tell these two species apart from each other, look at their:

- head – three-toed woodpeckers have two stripes, while black-backed woodpeckers have one

- back – three-toed woodpeckers have a striped back, while black-backed woodpeckers have a solid black back (the species name will help you here!)

Both species prefer burned trees, though they will also use trees killed by bark beetle outbreaks or storms, often spending long periods in one location drilling for insects. Three-toed woodpeckers forage rather shallowly on bark by flaking it off, while black-backed woodpeckers go deep for larger larvae.

Another confusing pair of lookalikes: Ladder-backed woodpecker (Dryobates scalaris) and Nuttall’s woodpecker (Picoides nuttallii)

Ok, here we go again with another confusing species pair! Here, geography will be your friend: Nuttall’s woodpecker is restricted to western California, while you will find the ladder-backed woodpecker in SE California, southern Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, western Texas, the Oklahoma/Arkansas/Mississippi intersection, and down into Mexico.

But, since you’re a keen birder, you’ll want to know how to tell these species apart – and you can sometimes find individuals outside their range! Plus, these two species are known to hybridize.

These are the most zebra-like of all the black and white species, and both have barred backs, barred flanks, and spotted wings. Only one other species – the red-cockaded woodpecker – also has these three traits. Red-cockaded woodpeckers have a black head with a large white cheek patch, while the ladder-backed and Nuttall’s have the more common pattern of two white facial stripes.

To distinguish these two species, the most straightforward overall feature to use is the amount of black (or white, depending on your point of view) – Nuttall’s have thinner white stripes (thicker black stripes) on their face and back compared to ladder-backed woodpeckers. If the back looks more black than white, it’s a Nuttall’s; if it looks more white than black, it’s a ladder-backed.

Nuttall’s inhabit California’s oak woodlands, whereas the wider-ranging ladder-backed prefers arid areas with cactus and mesquite. Both species will sometimes come to suet feeders, though ladder-backed prefer mealworms.

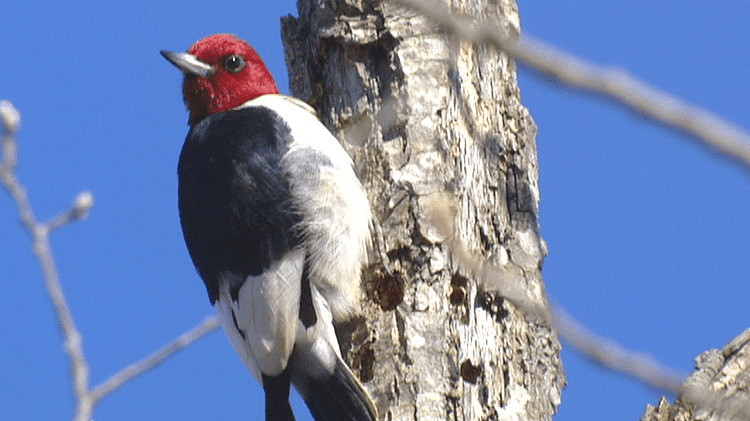

The woodpeckers with the most obvious name: Red-headed woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) and White-headed woodpecker (Picoides albolarvatus)

You got it – the red-headed woodpecker has a red head, and the white-headed woodpecker has a white head, making it hard to confuse either species with any other. The only other woodpecker with a completely red head is the red-breasted sapsucker, but their ranges barely overlap so geography will get you the correct species most of the time.

The red-breasted sapsucker is also a streaky bird, while the red-headed woodpecker is a solid black-and-white bird, so they are relatively easy to distinguish.

Besides their obvious names, the red-headed and white-headed woodpeckers don’t have much in common, so we’ll discuss them separately.

You can find the red-headed woodpecker in various human-modified habitats, from farms to orchards to trees in town. With its solid red head, solid white belly, black back and wings with a large white wing patch, and white upper tail coverts contrasting with a black tail, this is a striking bird.

Juveniles share the white wing patch and black tail but are generally brown elsewhere. Some northern populations move farther south in the winter, but central populations stay year-round, a pattern termed partial migration. This migration pattern may be due to their habitat of eating flying insects, fruits and seeds, which can be harder to find in northern areas during the winter.

The white-headed woodpecker has a small range restricted to mountain pine forests in Washington, Oregon, and California, where they feed mainly on pine seeds or superficially under bark or in needle clusters. It’s the most uniformly pattered of all the black and white woodpeckers, entirely black with a white head and throat and white bases of their primary feathers.

A triplet of woodpeckers that look alike but lack helpful names: Golden-fronted woodpecker (Melanerpes aurifrons), Red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus), and Gila woodpecker (Melanerpes uropygialis)

I wouldn’t use any of these species’ names to help me identify these birds! The golden-fronted woodpecker does have a bit of yellow near its bill, and the red-bellied woodpecker has a red wash over its lower belly. Yet neither of these traits is particularly obvious field marks to use when telling these species apart – and the name ‘Gila’ is not helpful at all.

All three species look similar but have essentially non-overlapping ranges, so check out what species you’re supposed to find in the area that you’re in, and that’s likely the one you’ve seen.

They all have a grey/brown head, throat, and belly, with black and white striping confined to their wings and back; this differentiates them from other woodpeckers. In all three species, the males have a red cap which the females lack. The differences among these species are in their tail and head:

-

Golden-fronted woodpeckers:

- white rump

- black central tail feathers

-

yellow above the beak, and a yellow/orange nape

-

Red-bellied woodpeckers:

- white rump

- barred central tail feathers

- red nape of the neck

-

Gila woodpeckers:

- barred rump

- barred central tail feathers

All three woodpeckers are more surface feeders than drillers and are omnivorous, eating whatever they encounter.

The Gila woodpecker is a desert scrub species of southern Arizona, Baja California, and western Mexico that nests in saguaro cacti where available. Its range includes the extreme southeast of California, where it is classified as Endangered due to habitat loss.

They use pecking, gleaning, and probing to find insects in cacti and trees, plus they will also eat berries and fruits (and sometimes even nestling birds), and will come to backyard feeders. They hybridize with golden-fronted woodpeckers.

Golden-fronted woodpeckers are found in brushlands and dry woodlands and will utilize urban areas and parks if enough trees are available. They also peck, glean, or probe to locate insects and spiders, consume fruit, and come to backyard feeders to feast on nuts, fruits, and seeds.

Red-bellied woodpeckers range the farthest east and are fairly generalist in their habitats, occupying woodlands, groves, orchards, and urban areas, and will come to backyard feeders. They’ll eat almost anything given a chance – seeds, fruits, acorns, nuts, and even lizards and minnows.

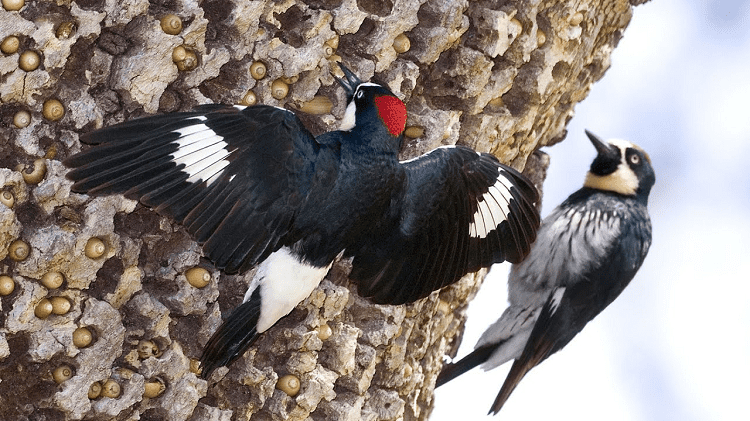

The Social Woodpecker: Acorn woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus)

This bird looks perpetually surprised because, unlike the other woodpeckers, it has a white iris. It also has a unique facial pattern, vaguely clown-like, with a black throat, a white ring that runs from the forehead down the sides of the head and joins at the chest, and a red cap. The female’s red cap is smaller than the male’s, with black at the front.

For the rest of their body, note the solid black back, black wings with white upper primaries, white rump and black tail, and a breast with a black patch that turns into streaked flanks. Once you see one, there’s no mistaking it for anything else.

The name of this species is one of the few that reflects behavior, not color. Since they rely on acorns as food during the winter, they require oaks in their habitat. However, they are also relatively tolerant of people and will continue to coexist in human-occupied habitats as long as acorns and a place to put them still exist.

This coexistence has occasionally put them in conflict with humans, as the birds sometimes use wood-sided buildings and utility poles to store their acorns instead of their typical dry bark on trees.

And they can store a lot of nuts – granaries can hold up to 50,000 acorns! Surprisingly, for such extensive and unique behaviors associated with acorn storage, their preferred food is insects, usually caught in flight, and they will eat sap, fruit, and nectar as well.

These are truly social birds, with pairs or polygynandrous (both sexes having multiple mates) groups laying eggs in the same nest. They also have helpers at the nest, usually the offspring of previous years, which both brood and feed nestlings. This system of helpers and cooperative polygynandry is unusual in birds, and it is unclear why it has evolved in this species.

The woodpecker in decline: Red-cockaded woodpecker (Leuconotopicus borealis)

This woodpecker looks fairly typical: barred back and wings, lightly barred sides and a mainly black head with a large white cheek patch; you won’t see any other woodpecker with a white cheek patch like that. Its name refers to a small patch of red beside its black cap – a ‘cockade’ is an ornament on a hat – but that red is rarely visible.

This is the only black and white woodpecker restricted to the southeast states. Historically, its range was more extensive, but it has been extirpated from several locations, which is probably why it currently has a disjunct and fragmented range. The range contraction is due to its specific habitat requirements: open pine woodland with trees that have heartwood disease.

It is the only woodpecker to use live pines, instead of dead trees, for nesting, and it can take 2-3 years to excavate one cavity. It also lives in groups, with sons helping their parents raise a new brood. It is believed that this cooperative group breeding behavior evolved because territories were limited, as happens when a species has a specific habitat requirement.

This species is listed as Near Threatened by IUCN, as its population is down to 1% of its former abundance. It is one of the best-studied woodpeckers; once its demise was noted in the 1960s, researchers started intensive study due to intense conflicts with the forestry industry.

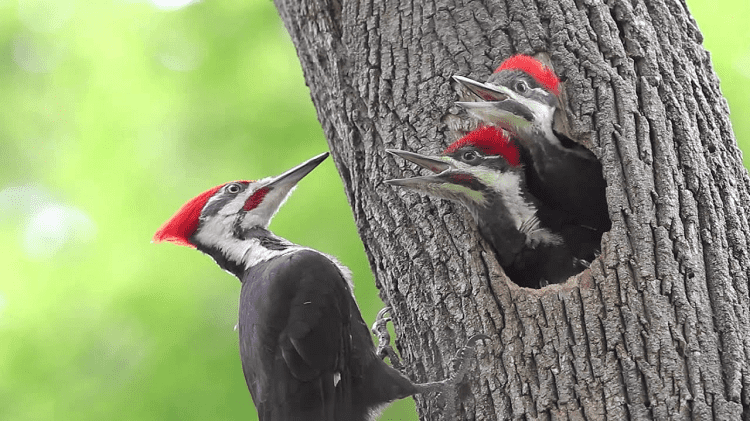

The Largest Woodpecker: Pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus)

The size of a pileated woodpecker makes it stand out not just among the black and white woodpeckers but among all the woodpeckers. Almost as big as a crow, this is the largest woodpecker in North America (assuming the ivory-billed woodpecker is extinct).

The pileated woodpecker is mainly black, with a white line above the eye, a white stripe from the beak to the back of the head that angles down along the side of the neck, and a white throat. It also has a red crest, and since the head feathers are usually erect, this is an unmistakable feature. Females have a black forehead, while males have a red forehead and a red mustache.

These birds defend territories in pairs year-round and require dead trees that are large enough to contain their nesting and roosting cavities. Thus the loss of older forests with larger trees likely limits their population size.

Since these large birds make large cavities, they are essential for providing nesting sites for cavity users with larger body sizes, including mammals, ducks, and owls.

They drill rectangular-shaped holes to get their insect prey, which is often small ants, somewhat surprising considering the large size of this bird. They use conifer, deciduous, and mixed forests across the middle of Canada and the southeastern US.

The (likely) extinct woodpecker: Ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis)

This is (was) the largest woodpecker in North America and the second largest in the world. There is still the tantalizing hope that it exists somewhere in the deep swamplands, but the last accepted sighting was in 1944. It also used to have a population in Cuba, but the last individual there was seen in 1987.

Thus this iconic species, sometimes called the “Good Lord” bird because that’s what people exclaimed when they saw it, has disappeared in our lifetime due to habitat destruction and hunting. Though not yet declared officially extinct, it is currently under review to change its designation.

Though superficially resembling the pileated woodpecker in North America, the ivory-billed has, as its name suggests, an ivory bill – a pileated has a black bill. The other noticeable difference is that the lower half of the wing on an ivory-billed woodpecker is pure white.

The Imperial woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis) also looks very similar, but their ranges don’t overlap – the Imperial is confined to Mexico. Combined with their large size, an ivory-billed woodpecker is hard to confuse with any other species – and you’d be famous if you ever documented one still alive!

The trio of confusing sapsuckers: Yellow-bellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius), Red-naped sapsucker (Sphyrapicus nuchalis), and Red-breasted sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber)

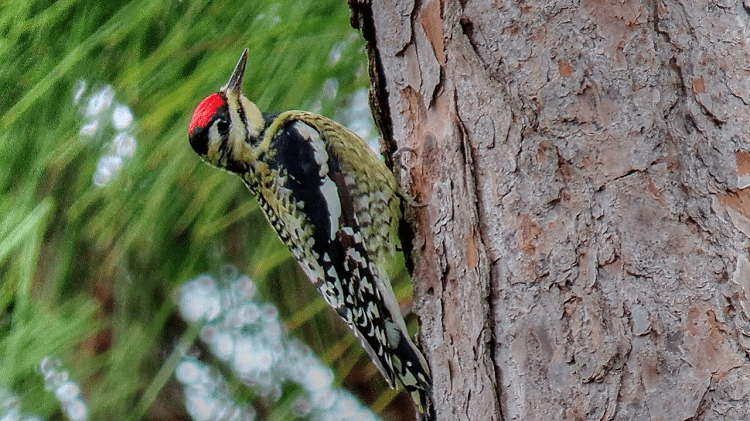

Sapsuckers are true woodpeckers, and all four North American species are in the same genus (Sphyrapicus). These three species look similar but have almost non-overlapping ranges. All three were considered the same species until 1983 and likely diverged only 0.8-0.4 mya – which is recent in evolutionary terms.

It’s still important to know which species is which if you’re in the small overlap zone, and hybrids (at least between red-breasted and red-naped sapsuckers) are known to occur regularly. All three species utilize the same types of habitat, mainly coniferous, mixed, or deciduous woodlands, and are all the same size (about 8.5 inches long).

All three have broad barring on their back, lightly barred flanks, and partially spotted wings with a solid white wing patch. They also have identical tails: white rumps, barred inner feathers, and black outer feathers. They differ in their head and throat patterns.

The red-breasted sapsucker is the easiest to identify, as it has a solid red head and breast. The red-naped and yellow-bellied sapsuckers are very similar in appearance. Look at these key features to distinguish them:

Red-Naped Sapsucker

- narrower white head stripes

- red patch on the nape of the neck

- black missing along the sides of the red throat patch

Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker

- broader white head stripes

- black nape of the neck

- black completely surrounds red throat patch

Sapsuckers behave differently from other woodpeckers. As their name suggests, they feed on the sap that exudes from a series of shallow wells drilled in a tree, and they defend this resource from other birds.

Their tongues are shorter and have stiffer hairs than other woodpeckers to help the sap adhere. They also eat insects, including ones that become trapped in the sap.

The red-breasted sapsucker is the most western species. Perhaps surprising for a bird with a limited range – it’s confirmed to the western edge of Canada and the United States – it exhibits partial migration, with inland breeding birds moving to coastal areas for the winter where they overlap with residents.

The red-naped sapsucker occupies the midwestern range of the United States and into Canada. The northern part of the population migrates south as far as Mexico, while some populations in the central range are non-migratory.

They are often associated with willow trees for sap but are found in deciduous and mixed forests and other diverse habitats across their range.

The yellow-bellied sapsucker has the widest range, breeding across the center of Canada and wintering across the southeastern United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

The cold winters of Canada may be why it cannot overwinter there, as sap does not flow in the winter. It has been recorded using over 1,000 species of perennial plants to obtain sap, perhaps explaining why this species has the widest distribution.

The Sexually Dimorphic Woodpecker: Williamson’s sapsucker (Sphyrapicus thyroideus)

Most male and female woodpeckers differ only by splashes of red, or yellow in a couple of cases, on their head or throat. Some species, like the red-headed woodpecker, have no differences between sexes.

Williamson’s sapsucker is at the other end of the spectrum – the males and females look very different. Upon seeing them, one would be forgiven if they thought they were different species (as early naturalists did). Williamson’s sapsucker diverged from the other three sapsuckers 2.8-5.2 mya.

A male Williamson’s sapsucker looks very distinct, with two long white facial stripes on a black head, a black back and throat, a large white patch in a mainly solid black wing, and a white rump above a black tail. Like the other sapsuckers, they have yellow on their body – though here, it’s on the belly.

A female is a brown, barred bird. They have a brown head with a finely barred throat, back, wings, flank, and tail. They share the yellow belly and white rump with the male, but those are the only two places where colors match.

This species prefers coniferous forests at mid-high elevations. They have a very fragmented range, and most northern populations migrate south in the winter. They have the highest dependence on ants of any woodpecker, gleaning these insects from the bark’s surface.

FAQs

Answer: In most black and white woodpeckers, males have red on their crowns while females do not, but this is not universally true. In the sapsuckers, males have more yellow on their heads than females, except for Williamson’s sapsucker, where the sexes look entirely different.

Answer: In some locations, extremely colorful! Especially if you’re in North America, it can be easy to forget that other woodpeckers sport more colors than ours typically do.

Take a look at species such as the crimson-mantled woodpecker, yellow-throated woodpecker, cream-colored woodpecker, or yellow-fronted woodpecker of South America; the chestnut-colored woodpecker of Central America; or the yellow-faced flameback of the Philippines.

Answer: In North America, the biggest and smallest come in the black and white variety – the smallest is the downy woodpecker at 5.5-7.1 inches long and 20-33g, while the largest that still exists is the pileated woodpecker at 16-19 inches long and 225-400g.

The likely extinct ivory-billed woodpecker was 19-21 inches long, and the Critically Endangered Imperial woodpecker, which only occurs in Mexico, is a whopping 22-23.5 inches long.

Conclusion

Black and white woodpeckers are a broad category based on superficially similar color patterns, and so doesn’t capture the subtleties of these birds. As you fine-tune your naturalist skills and work on identifying these species, ask yourself: is the black and white more like barring, spotting, or stripes? Is white or black predominant?

In some species, you have to pay attention to the back, wings, and tail, which means you also have to see enough of the bird to notice what is striped and what is solid colored.

As you pay more attention to the diversity this monochromatic palette can generate, you may better appreciate these feathered drillers that flit through the trees, carving out their habitat and, by doing so, creating habitat for other species.

References:

- Birds of the World

- Wikipedia

- All About Birds

- Peterson, R. T. (2020). Peterson field guide to birds of Western North America. Peterson Field Guides.

- Peterson, R. T. (1999). A field guide to the birds: eastern and central North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out:

- Red-bellied Woodpecker Guide

- Yellow-Bellied Woodpecker Guide: All You Need to Know about the Migratory Woodpecker with a Sweet Tooth

- Lewis’s Woodpecker Guide (Melanerpes Lewis)

- Nuttall’s Woodpecker Guide (Dryobates nuttallii)

- Downy Woodpecker Guide (Dryobates Pubescens)

- Red-naped Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus nuchalis)