- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

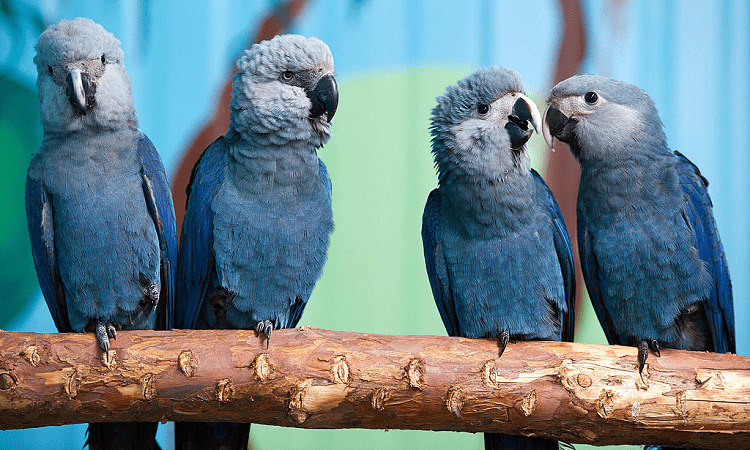

The Spix’s Macaw is currently the rarest parrot in the world – but hopefully, that will change in the coming years! This unusual species, known for its petite size and vibrant two-toned blue plumage, is so alluring that it was nearly driven to extinction first by specimen collectors and later by habitat destruction and poaching for the pet trade.

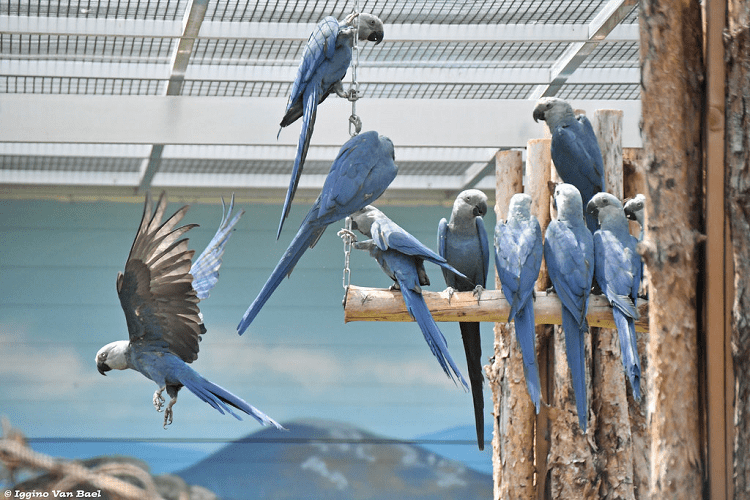

Today, it is considered extinct in the wild, but several ambitious conservation groups are attempting to resurrect the species as we speak. Wild-caught and pet birds alike are involved in a captive breeding program whose goal is to bring the species’ numbers and genetic diversity up as fast as possible.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because you may have seen it on the big screen – the 2011 movie “Rio” and its 2014 sequel “Rio 2” were, in fact, inspired by the Spix’s Macaw’s plight.

As of today, there are around 160 living Spix’s Macaws left in the world – but the good news is their numbers are increasing! In this guide, I’ll explain what makes the Spix’s Macaw so unique, give you a breakdown of its behavior, and provide an overview of the heroic conservation efforts that will hopefully bring this beautiful and unusual species back to the wild.

Taxonomy

The Spix’s Macaw is a member of the order Psittaciformes, which includes all 398 species of the world’s parrots in its 92 genera. Within the order, the Spix’s Macaw is further classified in the family Psittacidae, which contains around 360 species in its 80 genera.

The family Psittacidae, also known as “true parrots,” are forest birds of the world’s warmer regions and are rarely found in the temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere.

Parrots are known for their colorful plumage, hooked bills, short necks, large heads, and muscular tongues. They also have zygodactyl feet, in which two toes point forward and two point backward, which allow them to climb around in trees searching for fruit, nuts, and seeds.

Owing to its large size, the family Psittacidae is further broken down into two subfamilies: Psittacinae and Arinae. The Spix’s Macaw falls within the subfamily Arinae, which contains 150 species in its 32 genera.

Members of the subfamily Arinae – also called the “neotropical parrots” or “New World Parrots” – can be found in South America, Central America, Mexico, and on many Caribbean Islands. It includes the macaws, Amazon parrots, and the types of parakeets commonly called conures in the pet industry.

The subfamily Arinae is further divided into two tribes: Androglossini and Arini. The Spix’s Macaw is included in the tribe Arini, along with the larger macaws and smaller parakeets, also called conures.

The tribe contains 78 species in its 17 living genera, with five of these species being extinct, one possibly extinct, and one, the Spix’s Macaw, considered extinct in the wild.

Parrots of the tribe Arini have slender builds, long tails, and are excellent fliers. They are native to various habitats in Central America and South America. Six of the tribe Arini’s 17 genera are macaws.

The Spix’s Macaw is the only member of its genus, Cyanopsitta, which means “blue parrot” in Ancient Greek. The species was named for Johann Baptist Ritter von Spix – a German biologist who shot and collected a specimen in 1819 – but was actually first described by the German naturalist Georg Marcgrave in 1638.

It is also known as the Little Blue Macaw and the Ararinha Azul in its native Brazil.

The Spix’s Macaw is known – along with its South American cousins the Lear’s Macaw, Glaucous Macaw, and Hyacinth Macaw – as one of the “four blues.”

Taxonomy at a Glance

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Psittaciformes

- Family: Psittacidae

- Subfamily: Arinae

- Tribe: Arini

- Genus: Cyanopsitta

- Species: Cyanopsitta spixii

How to Identify the Spix’s Macaw

As the only small blue macaw in the world, Spix’s Macaws are distinctive and fairly unmistakable if you’re lucky enough to get a good look at one.

Adults

The Spix’s Macaw is a slender, elegant, medium-sized parrot. It is considered small for a macaw and big for a conure, instead falling somewhere in between. Including its tail, it has a length of about 22 inches when perched, with its tail alone being 10 to 15 inches long. In flight, it has a wingspan of 9.7 to 11.8 inches. It weighs about 11 ounces.

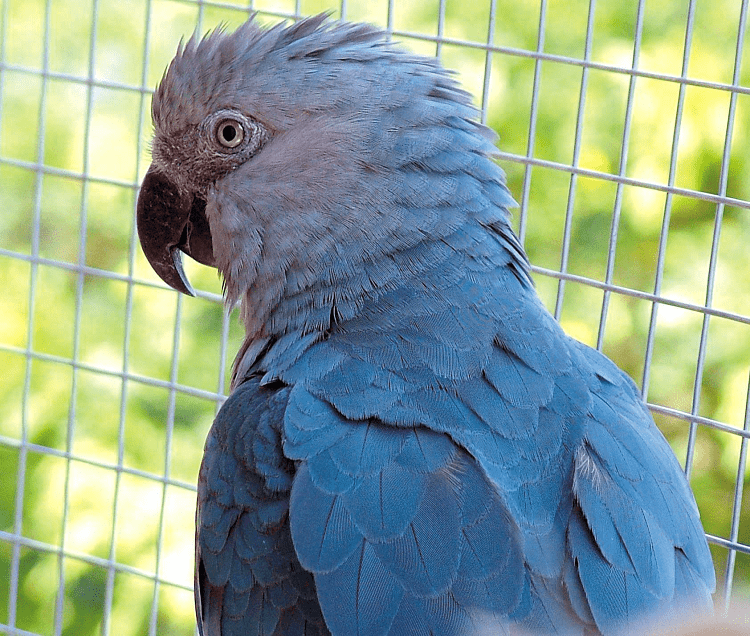

But what really makes this bird distinctive is its beautiful two-tone blue plumage. Its wings, tail, and back are a brilliant deep iridescent cerulean blue, while its belly and underparts are a lighter, more aquamarine blue. Its head, meanwhile, is a dusky gray with a slight blue tint.

Like all parrots, it has a hooked bill, which is dark gray in color. The naked skin around its nostrils, called a cere, is gray. Its lores – that is, the skin between the eyes and bill – are featherless and gray in color. Its legs and feet are gray with a brownish hue.

Adult Spix’s Macaws have yellow irises with dark black pupils. Males and females are nearly identical, with the females being slightly smaller.

Immature Birds

Juvenile Spix’s Macaws look similar to adults, but their plumage is a slightly darker shade of blue throughout. They also have dark eyes with brown irises. The skin around their nostrils and eyes is a paler whitish-gray compared to the darker gray of adults. They also have a vertical white stripe down the center, or culmen, of their otherwise dark bills.

Similar Species

Being the only small blue macaw, the Spix’s Macaw is fairly easy to identify. The other three species of blue macaw, in addition to being larger, also feature different markings and live in different habitats.

The Lear’s Macaw is a deeper more uniform shade of blue and has yellow skin around its eyes and near its bill. It is also five to seven inches longer from head to tail and lives near sandstone cliffs and palms.

The Hyacinth Macaw is a much deeper blue throughout and also has yellow skin around its eyes and bill. Having an impressive length of over three feet from head to tail, it is also a much larger bird. It is a species of open or sparsely wooded areas and, in theory, could overlap with the Spix’s Macaw’s range.

The critically endangered Glaucous Macaw has a gray head with turquoise body plumage like the Spix’s Macaw, but its last known range was in palm forests much farther south than the Spix’s range. It is also considered extremely rare, possibly even extinct.

On occasion, the Spix’s Macaw has been confused with the Red-bellied Macaw, especially when observed from a distance. The more common Red-bellied Macaw has a larger range and can be found in palm groves and swamp forests within sandy savannahs in Peru, Bolivia, and central Brazil.

It is a predominantly green parrot, with a large white to yellow patch of bare skin around its eyes as well as a big maroon patch on its belly.

The Blue-winged Macaw has a larger range throughout central and eastern South America but overlaps with the Spix’s Macaw’s range. As their name suggests, Blue-winged Macaws have blue wings like the Spix’s Macaw, but otherwise, they are mostly green.

They also have blue crowns and red foreheads with white to yellow patches of naked skin around their eyes.

Spix’s Macaw Vocalizations and Sounds

Like most parrots, Spix’s Macaws are known for their frequent loud vocalizations, but according to naturalist Johann Baptist Ritter von Spix, the species is “notable for its thin voice.”

Contact Call

The main vocalization of the Spix’s Macaw is a succinct grating “kra-ark,” which it issues repeatedly. When flying, a “kra-ark” call may be given every few feet. This is a contact call that the birds use to keep track of their flock mates.

Mating Call

Courting Spix’s Macaws issue a special call that starts as a low rumble and rises to a higher pitch, sounding like “witchaka!”

Listen to some captive Spix’s Macaws vocalizing in this video:

Other Vocalizations

Overall, the Spix’s Macaw has a more nasally and less shrill voice when compared with the ear-piercing shrieks of other larger macaws. They produce several different squawks and can even sound crow-like at times. Like many parrots, they can also mimic human speech and other sounds.

Where Does the Spix’s Macaw Live?

The Spix’s Macaw lives in groves of caraibeira trees along rivers in the Caatinga, or dry forest, ecological region of inland northeastern Brazil.

Range

The Spix’s Macaw has a very restricted range in northeastern Brazil. Historically, the species likely occurred along the Rio São Francisco river corridor between the cities of Juazeiro and Abaré in the state of Bahia, Brazil.

It was also found in parts of three other Brazilian states –northeastern Goias, southern Maranhao, and northeastern Piaui – and was once more common in the state of Pernambuco but has not been seen there since the 1960s.

The species’ last known population lived on the southern side of the Rio São Francisco river in northeastern Bahia.

Habitat

The Spix’s Macaw lives in stands of caraibeira trees (Tabebuia aurea), which grow along seasonal streams and rivers in the Caatinga biome, which is found only in northeastern Brazil.

Caatinga – which means “white forest” in Tupi – is made up of drought-tolerant small, thorny shrubs and cacti that take advantage of the three-month rainy season before dropping their leaves and going dormant for the majority of the year.

Small riparian groves of evenly spaced caraibeira trees, known as caraiba galleries, allow the Spix’s Macaw to live in the hottest and driest parts of the Caatinga.

The species associates closely with the caraibeira, relying on mature 200 to 300-year-old trees for foraging, nesting, and roosting. Without the caraibeira tree, the Spix’s Macaw would not be able to survive in this harsh dry biome.

Spix’s Macaw Migration

The Spix’s Macaw does not migrate, spending its whole life nesting and roosting within its preferred section of the Caatinga. However, flocks will travel great distances when foraging.

Spix’s Macaw Diet and Feeding

The Spix’s Macaw, like most parrots, has a preference for seeds, fruits, and nuts.

Seeds

The Spix’s Macaw eats the seeds of many plants native to the Caatinga biome, including those of the caraibeira (Tabebuia aurea), angico (Anadenanthera colubrina var. cebil), and many seeds of plants in the family Euphorbiaceae which dominate the Caatinga.

Seeds of the pinhão-bravo (Jatropha mollissima) and favela (Cnidoscolus quercifolius) make up the majority of the species’ diet in recent times, although these plants are newcomers to the Caatinga and were therefore not part of the Spix’s Macaw’s historical diet.

They also eat the seeds of unha-de-gató (Senegalia tenuifolia) and possibly mofumbo (Combretum leprosum).

Fruit

The Spix’s Macaw eats the fruits of many plants native to the Caatinga biome, including those of joazeiro (Ziziphus joazeiro), imburana (Commiphora leptophloes), blue torch cactus (Pilosocereus pachycladus), facheiro cactus (Facheiroa squamosa), many species of mistletoe (Phoradendron spp.), umbu (Spondias tuberosa), Maytenus rigida, and other species of cacti.

They also eat the fruit of Geoffroea spinosa trees.

Nuts

The Spix’s Macaw eats the nuts of many plants native to the Caatinga biome, including those of baraúna (Schinopsis brasiliensis). They also eat the nuts of the licuri palm (Syagrus coronata).

Other Food

In captivity, Spix’s Macaws eat a wide variety of seeds, fruits, and nuts. They also eat cactus flesh, flowers, leaves, and tree bark for supplemental minerals.

Spix’s Macaw Breeding

In the wild, the Spix’s Macaw’s breeding season starts in November and extends through March, which allows egg-laying to coincide with the Caatinga’s rainy season. In captivity, the season starts much later, usually in August.

Courtship

Historically, Spix’s Macaw males likely competed with each other for females and prime nesting sites. But, with no wild birds left to study, we can only speculate.

Captive Spix’s Macaws perform elaborate courtship rituals, including mutual feeding and coordinated flights. In other large parrot species, the courtship process can take many years. This is likely true for the Spix’s Macaw as well.

Like most parrots, Spix’s Macaws are monogamous and mate for life.

Nesting

Spix’s Macaws nest in existing cavities and hollows in large, mature caraibeira trees along rivers. To date, this is the only species of tree wild Spix’s Macaws are known to nest in. Caraibeira trees are long-lived and do not reach the preferred size for nesting until they are 200 to 300 years old.

While the Spix’s Macaws do not excavate their own cavities, they likely use their powerful hooked beaks to widen and modify existing holes like other parrots. Once an ideal nesting site is found, a pair will reuse it year after year.

Eggs

In the wild, a female Spix’s Macaw lays eggs every two days until a clutch of two to three white eggs is completed. The average clutch size is three eggs. Captive females lay a larger clutch of one to seven eggs, with four being the average.

The female performs incubation duties alone for 25 to 28 days, while the male feeds her by regurgitating.

Nestlings

In the wild, the eggs hatch in January, which is the beginning of the Caatinga’s three-month rainy season. The chicks are altricial – that is, mostly naked and helpless – when they first emerge from their shells. They are covered in a very sparse layer of white down.

Both parents diligently feed the young by regurgitation until they fledge the nest cavity at around two months old. Spix’s Macaw parents are very protective of their young and will perform distraction displays, laying on their sides on the ground to lure predators away from the nest.

The young remain with their parents for another three months after fledging, learning how to forage, avoid predators, and vocalize. They become independent at three to four months old but do not reach sexual maturity until they are two to four years old.

In captivity, they do not reach maturity until they are seven years old. This is likely due to captive life, inbreeding, or other unknown factors.

Spix’s Macaw Habits

Spix’s Macaws are social birds and likely spend most of their time foraging in noisy flocks, although they are reportedly shy compared to other large parrot species.

Foraging

Spix’s Macaws are known to travel in small flocks made up of several pairs and family members. They fly great distances each day, searching for fruits, nuts, and seeds by climbing around in trees and shrubs along seasonal waterways. They move across the Caatinga in response to food availability and rainfall.

Nest Defense

Like most parrots, Spix’s Macaws do not hold territories but will defend their nest sites from intruders.

Roosting

Spix’s Macaws roost high in the treetops at night, often in large caraibeira trees.

Spix’s Macaw Predators

By far, humans are the Spix’s Macaw’s biggest predators. Specimen collecting, hunting, habitat destruction and alteration, and trapping for the pet trade have all combined to lead to the species’ catastrophic decline.

Humans also introduced several animal species to the Caatinga that wreaked havoc on the Spix’s Macaw, including feral cats, mongooses, black rats, and marmoset monkeys, all of which feed on eggs and chicks.

The introduction of grazing animals like cows, sheep, and goats also harmed the Caatinga biome and made it impossible for new caraibeira tree seedlings to grow.

Introduced Africanized honeybees also pose a threat to Spix’s Macaws, as the bees swarm in tree hollows, attacking and killing chicks and adults alike.

Spix’s Macaw Lifespan

Like most parrots, Spix’s Macaws are relatively long-lived and have a lifespan of between 28 and 38 years. The oldest wild bird was at least 20 years old, but, as the species was poorly studied before its decline, it’s hard to say how long they typically live in the wild. The oldest captive bird lived to be 34 years old.

Spix’s Macaw Population

Until 2022, there were likely no Spix’s Macaws left in the wild. The last sightings of individual birds occurred sporadically in 1987, 2000, and 2016, and some of these could have been previously captive macaws that had been released by owners fearing prosecution.

As of June 2022, there are at least eight Spix’s Macaws living in the Caatinga of Bahia, Brazil. The birds are part of an elaborate captive breeding program whose goal is to reintroduce the species to the wild. 12 more Spix’s Macaws will be released by the end of 2022.

Currently, there are probably around 160 Spix’s Macaws living in captivity. Most are part of the conservation program, but a few others may be secretly kept as pets or are still being sold on the black market.

Is the Spix’s Macaw Extinct?

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the Spix’s Macaw as “extinct in the wild” in 2019, following the disappearance of the last known wild parrot in 2000 and years of surveys that failed to locate additional birds.

It remains to be seen if the species will be brought back from extinction following the current reintroduction efforts.

Why Did the Spix’s Macaw Go Extinct?

When Johann Baptist Ritter von Spix collected his Spix’s Macaw in 1819, the species was already considered rare. While specimen collecting and local hunting negatively impacted the species at first, habitat loss was by far the biggest blow.

The Spix’s Macaw is heavily dependent on the Caatinga biome, specifically, on mature caraibeira trees. Unfortunately, most of this rare and unique habitat was destroyed through burning, logging, and grazing as the Caatinga was colonized.

Heavy grazing by cows, sheep, and goats prevented new caraibeira tree seedlings from growing and most of the large trees were felled for firewood and to make way for agriculture. The riverside cairaba woodlands the birds relied on became scarce.

In 1957, introduced Africanized honeybees reached the Caatinga, out-competing the Spix’s Macaws for nest cavities. The aggressive bees would enter trees hollows in swarms and attack, killing the chicks and even the adult females present.

Then, in 1974, the Sobradinho Dam was installed above the city of Juazeiro on the Rio São Francisco river, flooding much of the Spix’s Macaw’s preferred habitat and making way for more agriculture along the river.

At the same time, trapping parrots for the pet trade – a practice that started in the 1960s – increased, continued throughout the 1970s, and reached a peak in 1980. Hundreds of thousands of parrots were illegally poached over several decades, with most dying during capture or transport.

And this didn’t just hurt the Spix’s Macaw. About 25% of all parrot species are threatened with extinction due to the devastating combination of habitat loss and poaching.

Reintroducing the Spix’s Macaw to the Wild

The reintroduction of the Spix’s Macaw to the wild is a joint effort of the government of Brazil, the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP), the Al Wabra Wildlife Preservation, the Lymington Foundation, Parrots International, and other conservation groups.

With no wild birds to work with, the groups focused their efforts on finding every single living Spix’s Macaw in captivity – both in zoos and private collections – starting in 1987.

Currently, all known captive parrots have been located and are now part of an effort to diversify the species’ gene pool as much as possible.

Ideal genetic matches are accomplished through artificial insemination, and young birds are hand-raised to ensure maximum survival. In 2013, there were 96 Spix’s Macaws in captivity, with only seven of wild-caught origin.

The groups planned to release their first birds once they had achieved a population of at least 150 parrots. They reached this goal in 2022 and successfully released the first eight birds alongside eight wild-caught Blue-winged Macaws, who would hopefully show the captive-bred birds how to forage and locate roost sites.

So far, all birds in the mixed flock are doing well in the wild and 12 more parrots will be released by the end of 2022.

This footage shows the newly released Spix’s Macaws exploring their wild habitat:

The reintroduction is a coordinated effort with the local communities, as key areas of the Caatinga are purchased, protected, and restored. Goats must be kept in pens to allow the biome to regrow, and older trees must be protected.

All possible nest sites are also monitored, and metal bands have been placed around the trees to deter predators.

The conservationists face many challenges, as no new caraibeira trees have been able to grow for the last 50 years and the parrots’ acceptable Caatinga habitat is still very limited.

A proposed wind energy development might also impact the conservation area, and efforts will have to be made to protect the parrots from wind turbine collisions.

In the past, other parrot reintroductions – most notably the attempted reintroduction of the extirpated Thick-billed Parrot to the mountains of southeastern Arizona in the 1980s – have failed.

Parrots are complex social creatures and the wild is very different from life in captivity. Still, as we speak there are eight Spix’s Macaws flying wild and free in the Caatinga of Brazil and that’s a pretty good start!

FAQs

Question: Is the Spix’s Macaw Extinct in 2022?

Answer: Technically, yes. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the Spix’s Macaw as “extinct in the wild” in 2019. There are, however, around 160 Spix’s Macaws currently living in captivity, and in June 2022 eight captive-bred parrots were reintroduced to the wild.

Question: Can I Keep a Spix’s Macaw as a Pet?

Answer: Technically, it is legal to own a Spix’s Macaw – but you would be hard pressed to find one that was bred in captivity and is available in the pet trade. Most of the Spix’s Macaws currently in captivity are part of a conservation program whose goal is to reintroduce the species to the wild.

It is illegal to capture a parrot from the wild. Spix’s Macaws – along with most parrot species – are included on the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) Appendix I, which is an agreement between governments that prohibits the trade of endangered species without a legitimate scientific, conservation, or educational purpose.

Question: Is the Movie “Rio” Based on a True Story?

Answer: Yes. The movie’s plot was based on the story of a Spix’s Macaw named Presley, who was illegally poached from Brazil in the 1970s and ended up in a loving home in Colorado, where he allegedly enjoyed the music of Elvis Presley.

When the owners took him to the vet in 2002, the vet explained to them how rare he was and they agreed to turn him over to the conservation groups in Brazil in the hopes that he might help save his species from extinction.

Presley died in 2014, but his testicles were cryogenically frozen in the hopes that he may continue to help his species in the future.

Question: Why Did the Spix’s Macaw Go Extinct?

Answer: The Spix’s Macaw went extinct mainly due to a combination of habitat loss and heavy poaching for the pet trade.

Most of its Caatinga habitat was cleared to make way for urban developments and agriculture and the loss of the big caraibeira trees it depended on for survival reduced populations at the same time it was being trapped in large numbers for the pet trade.

Question: Do Spix’s Macaws Mate for Life?

Answer: Yes. Like most parrots, Spix’s Macaws mate for life. They have a long courtship period of several seasons and once they have selected a mate, they are monogamous.

Research Citations:

Books

- Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Online

- American Bird Conservancy: https://abcbirds.org/bird/spixs-macaw/

- Animalia: https://animalia.bio/spixs-macaw#:~:text=The%20Spix’s%20macaw%20%2D%20also%20called,of%20dark%20grey%20featherless%20skin.

- Birdlife.org: http://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/spixs-macaw-cyanopsitta-spixii

- Lafeber Company: https://lafeber.com/pet-birds/presley-spixs-macaw-legacy/

- Science.org: https://www.science.org/content/article/two-decades-vanished-stunning-spixs-macaw-returns-forest-home

- Wikipedia.org: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spix%27s_macaw