- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

In North America, the Rufous Hummingbird easily wins first prize in the “tiny but mighty” category. While they are one of the smallest birds to visit the Northern Hemisphere, they also happen to be one of the most aggressive – anyone who has hung a nectar feeder quickly learns that the resident Rufous Hummingbird calls the shots.

Such tenacity may be merited, as these petite hummingbirds migrate a total of around 8,000 miles each year voyaging between their wintering and breeding grounds – quite a feat considering they are less than four inches long! When comparing distance traveled to body length, they undertake the longest journey of any bird in the world.

Still, despite all their pluck, Rufous Hummingbirds face many hardships and their numbers have declined in recent years. Luckily, there are some simple things you can do to help them out on their long journeys! In this guide, I’ll explain how to identify, enjoy, and assist these ferocious winged gems. Keep reading to learn all about the Rufous Hummingbird!

Taxonomy

Rufous Hummingbirds are one of around 361 currently described species in the family Trochilidae, which includes all of the world’s hummingbirds in its 113 genera. Ranging between two and nine inches in length, hummingbirds are the world’s smallest birds. They have long slender bills – used to access their preferred nectar food from deep within flowers – and can fly in all directions as well as hover.

Male hummingbirds typically have bright iridescent plumage that reflects sunlight to create dazzling arrays of color and often engage in dramatic courtship and territorial displays. Females are typically more drab and spend their time building nests and raising young. Due to their high metabolisms, all hummingbirds must feed frequently or enter a semi-dormant state called torpor.

Hummingbirds are found exclusively in the Americas and primarily live in more tropical climates which host the greatest diversity of the flowering plants they feed on, although there are a few notable exceptions. Some species, like the Rufous Hummingbird, make use of deserts and mountain meadows for at least part of the year.

The Rufous Hummingbird is one of nine species in the genus Selasphorus, which means “flame carrying” in Ancient Greek – likely a nod to their vibrant iridescence. Selasphorus hummingbirds – which also include the Calliope Hummingbird and Bumblebee Hummingbird – are found in Middle America and North America. German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin first described the Rufous Hummingbird in 1788. The species’ specific epithet, “rufus,” means “red” in Latin and refers to the bird’s copper-colored plumage.

Taxonomy at a Glance

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Apodiformes

- Family: Trochilidae

- Tribe: Mellisugini

- Genus: Selasphorus

- Species: Selasphorus rufus

How to Identify the Rufous Hummingbird

With their distinctive reddish coppery hue, adult male Rufous Hummingbirds are hard to miss in North America, although they may occasionally be confused with their close cousin, the Allen’s Hummingbird. As with most hummingbirds, females and juveniles are a little trickier to identify.

Adults

Adult Rufous Hummingbirds have large heads and tiny compact bodies measuring only 3.5 to 4 inches from head to tail. They have elongated bills that measure 15 to 19 millimeters long – about 18% of their total body length! When perched, their tails extend past their wingtips. But aside from these key characteristics, male and female Rufous Hummingbirds look quite different due to a phenomenon known as sexual dimorphism.

Males

Adult male Rufous Hummingbirds are truly resplendent. The plumage of their backs, wings, cheeks, and chests is predominantly a coppery red, while their lower underparts and bibs are cream to white. They also have white small white patches behind their eyes. Some birds – around 5% of the population – have greener backs with only a few red feathers but the majority have mostly red backs. In all cases, some back feathers have a little iridescence to them.

Their crowns, or the top of their heads, are bright green while their gorgets, or throats, are iridescent and contain hues of orange, scarlet, and gold. Hummingbirds rely on structural rather than pigment coloration to give them their shine, so their throat color can change significantly depending on light conditions and angles.

Check out this video of a male Rufous Hummingbird:

When perched, their rufous breasts give the impression that they are wearing red vests and create a white patch between their chests and gorgets and their long tails fold to a neatly tapered black-tipped point that extends past their wingtips. If you happen to get a good enough look, you’ll notice the fourth tail feather from the outside has a notched tip.

Because males usually guard a single food source and don’t have to fly as far while foraging, they have shorter wings than females. This allows them to beat their wings faster and, combined with their tiny bodies, makes them faster and more agile fliers – both strong assets for chasing off rivals and performing display flights. But, as a trade-off, they must expend more energy hovering. Male Rufous Hummingbirds are also slightly smaller than females and have longer bills.

Females

Because female Rufous Hummingbirds must rely on camouflage while incubating eggs, their plumage is more Earth-toned and cryptic. Their back and wing feathers are bright green, while their underparts are white. However, their flanks, sides, faces, and tails do show hints of rusty rufous coloring.

Female Rufous Hummingbirds have mostly ivory gorgets with green and bronze sides. In the center of their throats, they have a small reddish-orange iridescent patch that varies from a few shiny feathers to a well-defined diamond. As they age, they develop more iridescent gorget feathers.

Unlike their male counterparts, female Rufous Hummingbirds have rounded tails. Females are larger than males and have slightly shorter bills. They also have longer wings, which allows them to hover efficiently and travel greater distances to forage at various sites.

Immature Birds

Juvenile Rufous Hummingbirds of both sexes closely resemble adult females. Young males will often have a more defined gorget with larger individual iridescent feathers, while young females typically have less of a gorget and may lack one altogether, instead having a white throat. Still, immature hummingbird plumage is highly variable, and some juvenile females have quite defined gorget markings. Be on the lookout for youngsters in transitional plumage from June to November.

Subspecies

There are currently no subspecies of the Rufous Hummingbird.

Hybrids

Closely related hummingbirds may hybridize with the Rufous Hummingbird on occasion. Such birds show a mix of their parent species’ traits and behaviors and are an endless source of confusion for even the most advanced birders. Rufous x Calliope hybrids are the most common, but Rufous x Allen’s also occur.

Some birders claim to have encountered Rufous x Anna’s hybrids, but most of these are likely Allen’s x Anna’s. With Anna’s Hummingbirds expanding their range each year, such hybrids may become more common.

Similar Species

Hummingbirds – especially juveniles and females – can be challenging to distinguish from one another. Pay close attention to their markings and behavior and take note of where you are when you observe them. Do your best and know that even experts are often stumped by some hummingbirds! Below are the species most often confused with Rufous Hummingbirds across their range.

Allen’s Hummingbirds are so closely related to Rufous Hummingbirds that some ornithologists have considered merging the two into a single species. While very similar in appearance, adult male Allen’s Hummingbirds have narrower tail feathers, greener backs, and perform a U-shaped dive display. However, some male Rufous Hummingbirds feature more green on their backs, making identification a challenge – especially on the California and Oregon border where the two species’ ranges overlap.

Female and juvenile birds of the two species are nearly impossible to distinguish, and identifying green-backed males often requires a close examination of the spread-out tail feathers, which is rarely possible. For these reasons, many birders simply describe unverified sightings as Rufous/Allen’s Hummingbirds.

Broad-tailed Hummingbirds have grayer faces, larger and longer bills, less red on their tails, paler underparts, and are greener overall. Less colorful female Rufous Hummingbirds are easily mistaken for Broad-tailed Hummingbirds.

Calliope Hummingbirds have shorter tails, shorter bills, less red on their tails, and immature males have more wine-colored gorgets with longer and narrower edges. Less colorful female Rufous Hummingbirds are easily mistaken for Calliope Hummingbirds.

Bumblebee Hummingbirds have much shorter bills, shorter tails, less red on their tails, and immature males have more wine-colored gorgets.

Lucifer Hummingbirds are more slender, have longer gorget edges, have a slightly decurved bill, and have a long forked tail.

Bahama Woodstars have a very long forked tail, and females have unmarked throats.

Rufous Hummingbird Vocalizations and Sounds

Rufous Hummingbirds do not sing but produce a variety of calls and wing sounds unique to the species. Males also issue a distinctive vocal series as part of their dive display.

Calls

The Rufous Hummingbird’s most common call is a metallic “tik” or “chip” given singly, doubly, or triply.

Combat Call

Aggravated males defending a food source will issue a strong buzz before launching into a frantic series that sounds like “zee zikiti zikiti” or “zee zee-kik,” usually issued in flight as they chase off an intruder.

Alarm Call

Alarmed Rufous Hummingbirds will issue a squeaky buzzy “tsirr!” and a rapid series of chitters.

Wing Sounds

Due to their pointed outer flight feathers, the wings of adult male Rufous Hummingbirds create a shrill metallic-sounding whine as they fly, which is thought to act as the species’ song. Females and immature males do not produce this sound.

Rufous Hummingbirds of all ages create a deep buzzing sound with their wings while in flight. Like all Selasphorus hummingbirds, the Rufous Hummingbird’s wings buzz only while actively flying forward or backward and not while hovering. This can be very useful for identification.

Male Dive Calls

Near the end of their aerial dive display, adult male Rufous Hummingbirds issue a unique and unusually deep vocal series that sounds like a stuttering “je-je-je-deer.” As the series progresses, it drops in pitch before concluding with several popping sounds produced by the male’s tail feathers.

Where Does the Rufous Hummingbird Live?

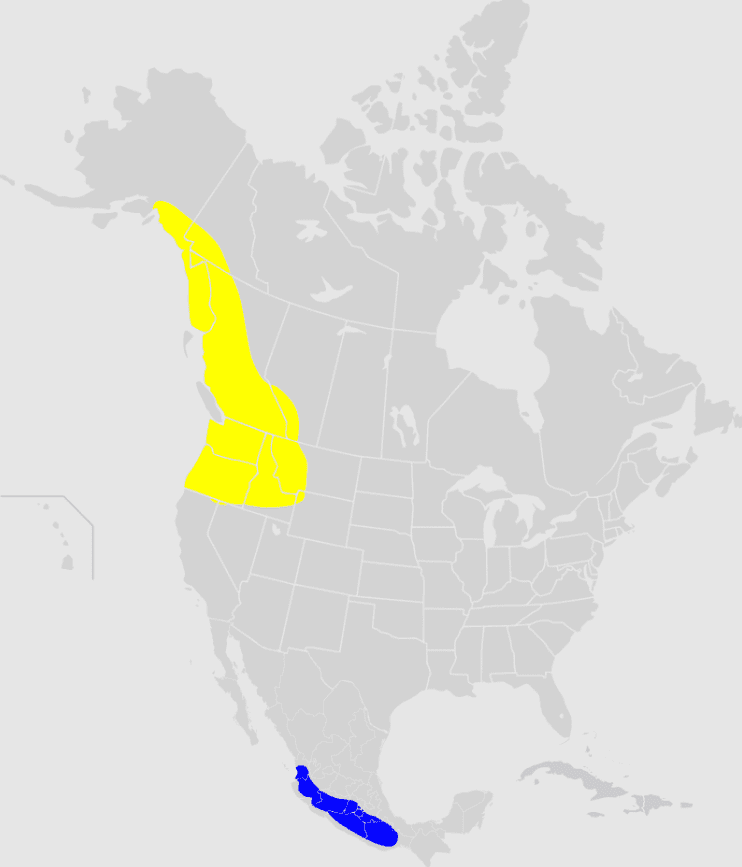

Rufous Hummingbirds are well-traveled birds. They are mostly found in western North America in late spring and summer and in southwestern Mexico during the winter. In the spring and fall, migrating birds may turn up incidentally across the United States.

Breeding Range

Of all hummingbirds, Rufous Hummingbirds breed the farthest north. In late spring and summer, these tiny birds can be found from coastal southeastern Alaska south through most of British Columbia and in Washington, Oregon, and extreme northern California. They also occur inland in southwestern Alberta, northwestern and central Idaho, and western Montana.

Migration Range

Migrating Rufous Hummingbirds can turn up just about anywhere in the United States but are mainly found in the western states of the U.S. and Mexico. They are most common in the Eastern United States between October and March but are more likely to be found in fall than spring.

Winter Range

Rufous Hummingbirds primarily winter in southwestern Mexico and are common in the Mexican states of Jalisco, Michoacán, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. Some birds also winter in coastal southern California and along the Gulf Coast in the U.S. states of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas, while northernmost populations may move to coastal regions or travel south and inland, seeking out yards with feeders and winter-blooming flowers.

On occasion, Rufous Hummingbirds will winter in gardens with feeders on the East Coast of the United States.

Breeding Habitat

Breeding Rufous Hummingbirds prefer some dense vegetation and can be found at forest edges, in forest clearings, in riparian woods along streamsides, in brushy second-growth coniferous forests, in mixed conifer and hardwood forests, in coastal temperate rainforests, in open woodlands, on brushy chaparral hillsides, in swamp thickets, in mountain meadows, and even in well-planted yards and parks.

Migration Habitat

During migration, Rufous Hummingbirds seek out lowlands and open mountain meadows with blooming flowers up to 12,600 feet elevation as well as gardens and yards with hummingbird feeders across the Western and occasionally the Eastern United States.

Winter Habitat

Wintering Rufous Hummingbirds can be found in a wider variety of habitats, including coastal scrub, scrubby second-growth thorn forests, pine-oak woodlands, and juniper forests up to 10,000 feet elevation in Mexico. Birds that winter in the north or the eastern United States require gardens with dense vegetation and winter-blooming flowers or feeders to survive.

Rufous Hummingbird Migration

Rufous Hummingbirds undergo one of the most impressive migrations in the bird world, traveling about 4,000 miles north to their breeding range in the spring and repeating the journey via a slightly different route in the fall – a phenomenon people first noticed when they began recognizing the same individual birds at feeders year to year. They spend most of their days on the move, completing an 8,000-mile clockwise circuit of North America each year.

Spring Migration

Rufous Hummingbirds leave their winter grounds and begin their journeys north in late February through early May. They travel northwest through lowlands along the Pacific Flyway – a common north-south bird migration zone that extends through western Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington, and western Canada – stopping at flowers and feeders along the way.

Migrating hummingbirds follow the flowers, making their way slowly north in short sections rather than one long flight. They often stay for one to two weeks at each stop.

Adult males leave first to ensure that they get first dibs on the best breeding territories, arriving in Washington state between late February and early March and the northernmost portion of their range in southeastern Alaska in early May. Adult females leave one to two weeks after the males, and juveniles follow later, often a full month behind the females.

Fall Migration

After the breeding season ends, Rufous Hummingbirds begin making their way south from late June through September. They take a slightly different route than they do in the spring, with some birds following the Pacific Flyway and others traveling southeast through the Rocky Mountains, feeding on late-blooming summer flowers in mountain meadows.

As in the spring migration, adult males begin the southward journey first, with females and juveniles following several weeks behind. Adult males first pass through western Colorado in late June and, as early as late July, they arrive in Arizona. Fall migrants are more likely to wander and may be found in gardens and at feeders across Canada and the Eastern United States.

Rufous Hummingbird Diet and Feeding

Like all hummingbirds, Rufous Hummingbirds feed primarily on flower nectar but supplement their sugary diet with insects for protein.

Nectar

Rufous Hummingbirds have a strong preference for short to medium-length red tubular flowers, including red penstemons (Penstemon spp.), skyrocket (Ipomopsis aggregata), Indian paintbrushes (Castilleja spp.), and scarlet sage (Salvia splendens).

They also feed on the flowers of red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), gilias (Gilia spp.), mints (Mentha spp.), lilies, bee balm (Monarda spp.), larkspurs (Delphinium spp.), heaths, fireweed (Chamaenerion angustifolium), honeysuckles, salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis), Rocky Mountain beeplant (Cleome serrulata), and red currant (Ribes spp.).

Sugar Water

Like most hummingbirds, Rufous Hummingbirds enjoy the sugar water solution offered in hummingbird feeders.

Note: If you choose to feed hummingbirds, always use a mixture of white table sugar and water in a ratio of 1-part sugar to 4-parts water. This concentration most closely mimics the nectar naturally found in flowers. Never use honey, other sugars, or red dye. If you store the mixture, boil the water first.

Be sure to change the sugar water and clean the feeder frequently to avoid the growth of bacteria and fungi than can be deadly to hummingbirds. Sugar water ferments to alcohol quickly in high temperatures and should be changed daily in hot weather.

Insects and Spiders

Rufous Hummingbirds frequently supplement their nectar-rich diet with small insects like gnats, flies, aphids, and midges for protein and fat. They also eat small spiders. Insects are an especially important food source for birds arriving on the breeding grounds in early spring before the flowers bloom as well as in winter.

Other Food

On occasion, Rufous Hummingbirds drink tree sap from wells created by sapsuckers.

Rufous Hummingbird Breeding

The Rufous Hummingbird breeding season starts in March and extends through July. Male and female Rufous Hummingbirds have very different roles when it comes to breeding. Males spend most of their energy viciously defending a food source and displaying, while females build the nest, incubate the eggs, and raise the young solo. They raise one brood each year.

Dive Display

Male Rufous Hummingbirds arrive on the breeding grounds first in the spring and immediately begin defending the best nectar source, whether it be a flower patch or feeder. Courtship begins when a female enters a male’s territory. To impress her, a male Rufous Hummingbird will climb high into the air and then perform a steep oval or J-shaped dive, issuing a deep, stuttery “je-je-je-deer” call and a series of pops and whines using his tail feathers at the bottom.

Males often repeat their performance multiple times. Dive displays are performed year-round, even during migration. Immature males will also practice diving, although they often lack the vocalization and tail popping sounds at first.

Shuttle Display

Should a perched female appear interested, the male will often zoom back and forth in front of her in a series of horizontal figure eights in what is known as a shuttle display. Such displays are also used to intimidate rivals. Compared to other hummingbird species, Rufous Hummingbirds perform a more three-dimensional shuttle display.

The female may respond to the male’s advances with a shuttle display of her own – this often precedes mating. After mating, the two go their separate ways. A single male Rufous Hummingbird typically mates with many females over the course of a breeding season.

Nesting

Nesting occurs from mid-April to mid-July. The tasks of selecting a nest site and building the nest fall solely on the female Rufous Hummingbird. Within three days of arriving on the breeding grounds, a female will begin scouting possible nest sites. Preferred locations are between three and 30 feet off the ground in the lower branches of dense coniferous trees, in deciduous shrubs, or in vines.

Rufous Hummingbirds have been known to nest in Western hemlock, Sitka spruce, Douglas fir, Western redcedar, birch, and maple trees as well as thimbleberry bushes, creeper vines, and ferns.

Nests are typically built on drooping or horizontal twigs or in branch forks. Because of their specific preferences, female Rufous Hummingbirds often end up nesting near one another and up to 20 nests were once discovered in the same tree in Washington. Most nests are found less than 15 feet above the ground, but nests built later in the season are higher up.

The female then constructs a small, thick-walled cup nest about two inches in diameter and one and a half inches deep. She first fashions the cup out of soft materials like plant down and feathers then conceals the lighter materials with lichen and moss to camouflage it. The nest is glued together with spider silk. In some instances, a female will spruce up and reuse a previous season’s nest, though not always one she built herself.

Eggs

Once the nest is complete, the female Rufous Hummingbird lays her eggs. Two is the most common clutch size, but rarely only one egg or up to four are laid. The tiny eggs are white, elliptical, smooth but not glossy, and are about half an inch long. The female incubates the eggs by herself for 15 to 17 days, taking breaks only to feed.

Nestlings

Young Rufous Hummingbirds are altricial, meaning they hatch completely helpless. The chicks have dark skin and are mostly naked save for two lines of gray down on their backs. The female feeds her young by herself, probing her long bill into their mouths and regurgitating a rich mixture of nectar and insects. She aggressively defends her nest, even chasing away larger animals like chipmunks.

At six days old, the young open their eyes. Their baby down gradually lengthens before giving way to pinfeathers when they are about one week old. They grow rapidly and are able to fly at just 21 days old, fledging around May.

Rufous Hummingbird Habits

Due to their high metabolisms, Rufous Hummingbirds spend most of their lives searching for nectar sources and feeding. Once they locate a reliable source, they devote a great deal of energy to defending it.

Foraging

Rufous Hummingbirds must feed often during the day. Because of this extreme need to feed, they have excellent memories and can remember the exact locations of choice flower patches and feeders. They can even remember feeders from years prior and will return to check on a location where a feeder once was even if it has since been removed.

Rufous Hummingbirds hover before their food source, extracting the sugary liquid with their tongues. They fly from flower to flower in fast straight lines all day long, often repeating the same sequence over and over in a behavior known as trap-lining. Sapsucker wells are also visited regularly.

They also capture insect prey in a variety of ways, snatching flying insects right out of the air, plucking them from beneath leaves or from spider webs, picking eggs from surfaces, or engaging in a behavior called leaf-rolling, in which they use their wings to blast air onto leaf litter to locate hidden prey.

Territorial Defense

All Rufous Hummingbirds – including juveniles and females – are extremely aggressive and territorial at all times of the year. In fact, they are considered the most aggressive species of hummingbird in North America. Migrating Rufous Hummingbirds have even been known to chase off larger species like Black-chinned Hummingbirds, Broad-billed Hummingbirds, Violet-eared Hummingbirds, and Broad-tailed Hummingbirds – even on their own turf!

Male Rufous Hummingbirds are the most territorial, staking out a flower patch or nectar source, monitoring it from a nearby perch, and ruthlessly defending it. Should an intruder venture near, the male Rufous will flash his gorget, fan his tail, and chip agitatedly. If the interloper does not take the hint, he will perform an intimidating shuttle display or give chase. Male Rufous Hummingbirds will even chase females away from food sources during the breeding season.

Torpor

Like most hummingbirds, Rufous Hummingbirds enter a partial hibernation state during the night to conserve energy. During this dormancy, known as torpor, hummingbirds lower their body temperatures significantly, relying on fat reserves to heat them just enough to stay alive. It takes them about an hour to emerge from a state of torpor and during this time they are most vulnerable to predators.

Rufous Hummingbird Predators

When they aren’t in torpor, Rufous Hummingbirds are quite difficult to catch. Still, skilled avian hunters like American Kestrels, Merlins, Loggerhead Shrikes, Greater Roadrunners, and Sharp-shinned Hawks have been known to prey on them. Brown-crested Flycatchers and other insect-eating birds have also occasionally captured a Rufous Hummingbird and owls can ambush them at night while they are in torpor.

Other predators include cats, snakes, lizards, and fish. Large mantids and orb weaver spiders have also managed to successfully kill hummingbirds. Nesting females are vulnerable to squirrels, rats, chipmunks, and snakes, and corvids, orioles, grackles, and tanagers will feast on nestlings and eggs if given the chance. Other threats to Rufous Hummingbirds include window collisions, pesticides, and exposure to pathogens in bad feeder water.

Rufous Hummingbird Lifespan

The oldest Rufous Hummingbird was at least eight years and 11 months old when captured in British Columbia. The bird was a female, which is not surprising considering females live longer on average. Males often exhaust themselves in aggressive altercations and fail to feed themselves adequately, shortening their lifespans.

Rufous Hummingbird Population

Rufous Hummingbirds are still considered widespread and abundant throughout their range, but significant declines have been observed in recent years. According to the North American Breeding Bird Survey, their numbers have decreased 67% between 1966 and 2019 – a steady decline of about 2% per year. Still, Partners in Flight estimates a global breeding population of 22 million birds.

Is the Rufous Hummingbird Endangered?

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) listed the Rufous Hummingbird as Near Threatened in 2018 due to its declining population, meaning it is a species at risk of extinction without some intervention. In addition, Partners of Flight added the Rufous Hummingbird to its Yellow Watch List, which includes birds most at risk of extinction without significant conservation efforts.

Experts aren’t sure exactly what is causing the declines, but they suspect habitat destruction, climate change, and pesticide use play significant roles. Logging throughout the Rufous Hummingbird’s breeding and winter ranges has removed the dense vegetation they require to nest and shelter in. Meanwhile, warming temperatures cause flowers to bloom two weeks earlier in some areas, meaning the birds have no food source when they arrive on their breeding grounds.

Rufous Hummingbirds also rely on insect prey during the winter months and so face the detrimental effects of pesticides. And feeders bring the birds into our yards, where they face increased risks of window collisions and predation by cats. To make matters worse, because the species has a long dangerous migration and a short breeding season, it is not able to respond quickly to population declines. These fierce little birds need our help!

FAQs

Answer: You can help Rufous Hummingbirds by making your yard a bird-friendly oasis. If you live within the species’ range, cultivate a hummingbird garden full of their favorite flowers such as red penstemon and scarlet sage. Also provide some dense vegetation for nest and roost sites. If you choose to hang a feeder, make sure you are preparing the sugar water correctly and changing the mixture often.

Add decals or Acopian BirdSavers to your windows to prevent collisions and always make sure you keep your cats indoors. You can help Rufous Hummingbirds on a larger scale by passing legislation that protects their habitats, restricts irresponsible pesticide use, and promotes Earth-friendly initiatives.

Answer: No. Rufous Hummingbirds focus most of their aggression on other hummingbirds and pose no risk to humans. In fact, if you are the one regularly changing the hummingbird feeder your resident Rufous Hummingbird likely recognizes you. Rufous Hummingbirds are fearless at times and may perform display dives, hover, or perch close to people.

Answer: Rufous Hummingbirds are smaller than Anna’s Hummingbirds. Adult male Rufous Hummingbirds have red bodies while adult male Anna’s Hummingbirds are mostly green. Juvenile and female Rufous Hummingbirds have rusty flanks while Anna’s Hummingbirds’ flanks are grayish green.

Their vocalizations are also quite different. An Anna’s Hummingbird often sings a long buzzy series while Rufous Hummingbirds mainly issue short series of “tick” and “chip” calls. Anna’s Hummingbirds make a single loud whistle while diving while Rufous Hummingbirds issue a deep “je-je-je-deer” call along with popping sounds.

Their combat calls, often heard at feeders, are also different. Anna’s Hummingbirds produce an emphatic “zeega zeega zeega!” while Rufous Hummingbirds issue a series that sounds like “zee zikiti zikiti” or “zee zee-kik.”

Research Citations

Books

- Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

- Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

- Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Sibley, D.A. (2000). The Sibley Guide to Birds (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Williamson, S.L. (2001). Hummingbirds of North America (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Online

- The Cornell Lab of Ornithology All About Birds

- Hummingbird Hybrid Zone

- Hummingbird Predators

- International Ornithologists’ Union (IOC) World Bird List

- Wikipedia

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: