- Gray Hawk Guide (Buteo plagiatus) - October 25, 2022

- Swainson’s Hawk Guide (Buteo swainsoni) - October 19, 2022

- Harris’s Hawk Guide (Parabuteo unicinctus) - September 26, 2022

Birds of prey are incredible birds, and Harris’s Hawks are no exception.

Unique in their coloring and highly sociable, Harris’s Hawks glide and soar in the sky and are usually easy birds of prey to spot. These hawks hunt in groups, giving them the nickname wolf hawks.

Diurnal by nature, Harris’s Hawks are also popular birds used for falconry because of their social nature and easy bonding with humans.

One of the most famous Harris’s Hawks is Rufus.

Rufus helps to keep pigeons away from the tennis courts during Wimbledon in the UK every summer. He is the grandson of Hamish, the first Harris’s Hawk used to help with the pigeon problem that plagues London.

Castor and Pollux are another two hawks that help clear Wimbledon of pigeons early in the mornings before the crowds come in.

And before you wonder, the pigeons are not hurt by the hawks. They only get chased away, hopefully getting the message that it is unsafe for them to roost there!

Taxonomy At a Glance

- Domain: Eukaryota

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Accipitriformes

- Family: Accipitridae

- Genus: Parabuteo

- Species: Parabuteo unicinctus

Two subspecies

- Parabuteo unicinctus harrisi (Harris’s Hawk)

- mainly found in Southwest USA

- Parabuteo unicinctus unicinctus (Bay-winged Hawk)

- mainly found in South America

| Identification | Dark, chocolate brown with chestnut-colored wing patches and linings

Long yellow legs and toes Hooked bill and naked lores between bill and eyes Long tail is dark brown, almost black, with white tip and white base |

| Habitat | Desert scrub

Grassland Wetlands Savanna Southwest USA, Central and South America |

| Diet and Feeding | Birds

Lizards Small to medium-sized mammals (like hares and rabbits) |

| Breeding | In groups |

| Nesting | Nests built or repaired between January and August

Returns to same nests |

| Eggs | First clutch in March/April

1-5 eggs, though mostly 3-4 eggs |

| Population | 55 million |

| Endangered | No |

| Habits | Cooperative hunting

Perching together as a group on power poles and lines Shoulder-standing / back-stacking |

| Predators | Human activity that results in habitat loss or persecution

Wild birds taken for falconry Great horned owls, coyotes and ravens attack nestlings |

| Lifespan | 11 – 12 years average in the wild |

How to Identify A Harris’s Hawk

Harris’s Hawks are part of the family of Hawks, Kites, and Eagles (known as Accipitridae).

Their coloring is distinctive and unique amongst hawks. Harris’s Hawks are dark, chocolate brown with chestnut-colored wing patches and linings.

Their tail is long and dark brown, almost black, with the tip and base of the tail white.

Legs are also long. The upper, feathery part of the leg is chestnut, whereas the lower leg and toes are yellow.

They have a classic bird of prey hooked bill and naked lores between the bill and eyes, which tends to make the bill look bigger than it is.

Juveniles are similar to adults but have cream-colored streaks on the breast and belly and cream-colored bars on the chestnut part of the legs.

You often find with birds of prey that females are larger than males; so it is for Harris’s Hawks. The weight of a female is 775g to 1630g, whereas that of a male is 515g to 880g.

Their length is between 46 and 59 cm, and the wingspan is 103 to 119 cm.

There are slight differences between the subspecies: the Bay-winged Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus unicinctus) has a smaller body and a longer tail than the Harris’s Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus harrisi). The Bay-winged Hawk also has whitish streaks or flecks on its belly.

Where Do Harris’s Hawks Live: Habitat

You can find populations in parts of Southwest USA: Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, and less commonly in California.

In Central and South America, scattered populations breed in countries such as Mexico and Costa Rica and the western parts of Columbia, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile. Subspecies of Harris’s Hawks have also been observed in northern Venezuela, eastern Bolivia, Paraguay, and eastern Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina.

Harris’s Hawks love a variety of habitats: desert scrub, grassland, wetlands, and savanna. However, they are moving into urban areas with not too many houses and still some open space. In these areas, there is plenty of prey, water, and hardly any threats from humans, which has helped the population grow.

Sizable trees or other structures such as power poles, dead trees, and cacti serve as places for perching, often preceding a hunt, and for nesting.

Less is known regarding the Harris’s Hawks in South America though it has been found that the hawks inhabited ravines in the mountains of Chile rather than flat open spaces. Increasingly Harris’s Hawks are moving to urban areas of Chile as well. Further study is needed as there is not enough data (particularly about the hawks in Central and South America).

Harris’s Hawks are resident birds of prey that stay in their territory all year round. They do not tend to migrate or move around though a young bird may roam further afield. It may also be a falconry hawk who escaped from captivity and is outside their usual territories.

Harris’s Hawk Diet and Feeding

Harris’s Hawks hunt in cooperative groups and feed on birds, lizards, and small to medium-sized mammals such as rabbits and hares.

They drink from, stand, and bathe in cattle tanks and ponds, particularly in hot weather. Since one of their main habitats is desert scrub or savanna, it is no surprise they will find anything to keep cool!

Interestingly, in South America, no cooperative hunting is reported to be witnessed in Harris’s Hawks. There is a call for more research and data on the South American species as there is not much known about them compared to the subspecies in the USA.

After a successful, cooperative hunt, Harris’s Hawks share their captured prey, following the hierarchy and ranking of the birds in the group.

Harris’s Hawk Breeding

Breeding is a family affair for Harris’s Hawks, especially for the hawks in Southwest USA. They live together in groups of two to seven individuals.

Studies of the hawks show that there are two types of helpers in these breeding groups (though rare in South America).

Firstly, there are adult helpers who are not related but help out with the breeding hawks.

The second type of helper is one of the youngsters. They remain close to their parents and where they were born for up to three years.

The cooperative nature of the hawks extends to raising the young. Three adults will tend to a nest, usually two males and one female. The female incubates the eggs for 31 – 36 days while the helpers hunt for food, bring it back to her, and help feed the young. The second male, a helper, may well be one of her offspring from a previous year.

Breeding together in groups and the cooperative hunting behavior of Harris’s Hawks appear to contribute to an increased survival rate of the hawks. They get more than if they hunted on their own. There is more food available more regularly. Also, they can hunt bigger prey by working together in teams.

Harris’s Hawk Nesting

Harris’s Hawks start building their nests about five weeks before the female lays her eggs. Nest-building happens between January and August, and some nests are reused and repaired. Trees are the preferred sites for nest building, such as paloverde trees and saguaro cacti in Arizona. In New Mexico, the hawks use mesquites, and in Texas, they mostly use live oaks.

Harris’s Hawks may use other trees in more urban areas, like pine trees. In some cases, they occupy manufactured structures such as weather antennae and electrical transmission towers.

Females do most of the nest building, though males contribute as well but not as much. A breeding pair may construct or fix up to four nests. Mostly dead sticks are used, with fresh sprigs or feathers for the lining.

Harris’s Hawk Eggs

The female lays her first clutch around March and April.

She may lay up to two more clutches after this time, especially if the first attempt has been unsuccessful.

There is anything from one to five eggs in a clutch, though it is usually three or four eggs.

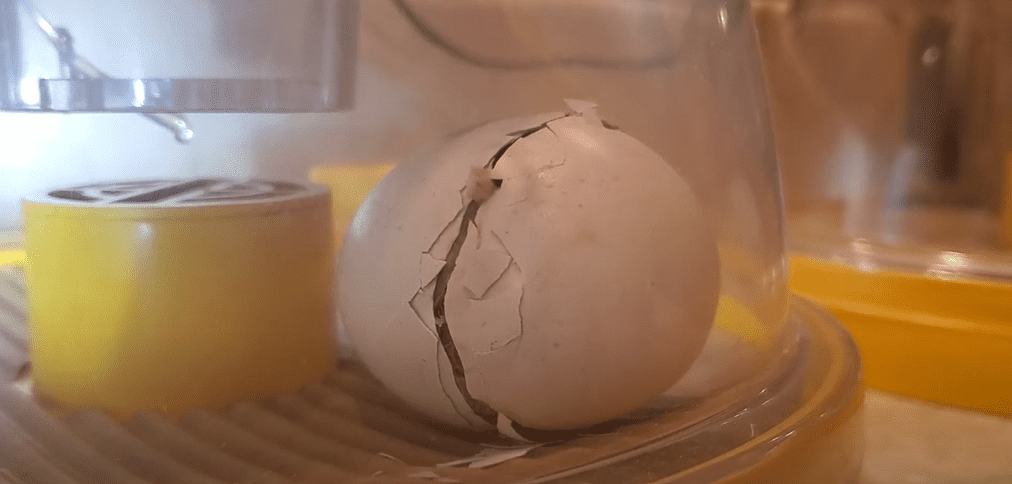

Unfortunately, eggs not hatching seems to be a recurring problem for Harris’s Hawks. It suggests perhaps disease or infertility. The eggs and nestlings are also vulnerable to storms, which sadly causes them to fall from the nests.

Harris’s Hawk Population

According to the American Bird Conservancy, Harris’s Hawk population is 55 million.

Harris’s Hawks stay in their natal territory all year round, reusing the same nests for a few years. However, there have been instances where entire groups of hawks have disappeared. It is thought they have either moved on or, worse, been killed by electrocution as they love to hang out on power poles and power lines.

Populations rely on what is available regarding prey, nesting possibilities, perches for hunting, and water access; if these are no longer accessible or suitable, a group may move on to another territory.

In Central and South America, the Harris’s Hawks may be more nomadic and migratory, moving north or south. Again, there has not been enough study into the hawks in these areas, and more is needed.

Are Harris’s Hawks Endangered?

Conservation status is rated Least Concern for Harris’s Hawks.

Habitat loss has endangered Harris’s Hawks, and populations have been affected. Drought and wildfires caused by climate change also have an impact.

There has been an impact on populations due to urbanization, though, as I mentioned before, urban areas are now attracting more Harris’s Hawks, and they are living relatively peacefully side by side with humans.

A reintroduction program was set up in 1979-1989 to release 200 Harris’s Hawks near the Colorado River between Arizona and California. It was successful for the short term.

Unfortunately, the program did not release any more hawks after that time. One of the reasons is that the habitat was not being restored accordingly. The population may decrease as a result.

Harris’s Hawk Habits

Harris’s Hawks have a habit of standing on top of the shoulders of one another to elevate themselves to hunt, called shoulder-standing or back-stacking. They also place themselves close together on perches before commencing a hunt together.

This behavior makes it easy to spot Harris’s Hawks, as no other bird of prey does this.

Harris’s Hawks hunt in groups, much like a wolf pack. When they hunt independently, they tend to perch and wait before striking.

In cooperative hunting, they employ different tactics. Two hawks or more may perch on separate poles, for example, and then dive for prey below simultaneously.

Another tactic is for one of the hawks to flush out hidden prey while the others in the group are waiting on nearby perches to catch it once it appears. During a chase, the lead hawk in pursuit of a mammal will swap with others in a relay manner.

Harris’s Hawk Predators

Mostly humans! Human activity has caused the habitat that Harris’s Hawks thrive in to decrease. Other threats include electrocution since Harris’s Hawks use power poles to perch to gain height for hunting.

Many are injured due to electrocution, not just killed, though it appears that when there is an injured hawk in the group, the others will look after it and bring it food, for example, so some survive their injuries.

Over the years, utility companies have made efforts to ensure the power poles and structures are less dangerous for birds like Harris’s Hawks.

The capture of Harris’s Hawks for falconry is another threat. There have also been cases where the birds have been killed by drowning, shooting, or colliding with a vehicle.

Great horned owls, coyotes, and ravens threaten eggs and nestlings.

Harris’s Hawk Lifespan

The oldest female captive Harris’s Hawk is Cheyenne at the Freedom Center for Wildlife in New Jersey. She celebrated her 36th birthday in March 2021.

As for the oldest wild Harris’s Hawk, there are differing reports. A banded male in New Mexico was thought to be 11 years old. In the book Birds of Prey, a table shows a banded Harris’s Hawk was 12 years and seven months old.

FAQs

Answer: The hawk is named after Edward Harris, an American ornithology friend of John James Audubon. Harris supported Audubon financially and even went on birding expeditions with him.

Answer: A Harris’s Hawk is 46 to 59 cm with a wingspan of 103 to 119 cm. Females are usually larger than males, up to 47% heavier.

Answer: Harris’s Hawks eat small to medium-sized mammals (like hares and rabbits), lizards, and birds.

Research Citations

- Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2021. The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the World: v2021.

- Dunn, J.L. and Alderfer, J. (2006) National Geographic: Field Guide to the Birds of North America. 5th ed. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

- Newton, I. (2000) Birds of Prey. Reprint. San Francisco: Fog City Press.

- Dwyer, J. F. and J. C. Bednarz (2020). Harris’s Hawk (Parabuteo unicinctus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

- https://www.businessinsider.com/rufus-hawk-wimbledon-tennis-matches-pigeon-scarer-bird-hamish-2022-6?op=1&r=US&IR=T

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Harriss_Hawk/

- https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/harriss-hawk

Looking For More Interesting Readings? Check out