- Best Amazon Bird Baths Guide - September 26, 2023

- Best Copper Bird Baths - August 30, 2023

- Best Bird Baths Available at Home Depot - August 26, 2023

This hummingbird has a fantastic name that made me excited to learn about it – I’ve never been fortunate enough to see one in person. I mean, when you hear the name ‘starthroat,’ it just has to be a stunner, right?

Unfortunately for us bird watchers, the name doesn’t quite live up to our expectations, and it doesn’t really help with species identification in this case either.

And unfortunately for us bird lovers, there is not a lot known about the biology of this species, and it’s not clear why – I would guess that it’s simply a product of location (there are more tropical than temperate species and so more birds to learn about once you move south of North America).

However, as a biologist that has spent years studying birds in several countries, I realize there is much to learn even about species in our backyard, and it can be challenging to choose which species to study – the charismatic and pretty ones tend to get more focus than duller species, and the plain-capped starthroat falls into the latter category.

Bottom Line Up Front

The plain-capped starthroat is a recent addition to the North American avifauna, first recorded as a vagrant in Arizona in 1969, and has visited that state fairly regularly since then during the non-breeding season.

Occurring in many types of forests along the Pacific slope normally in Mexico and Central America, while we know some information about its habitat use, other aspects of its basic biology are not known, making the plain-capped starthroat yet another overlooked species that we know little about.

Taxonomy

Plain-capped starthroats are classified using the following taxonomy:

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Apodiformes

- Family: Trochilidae

- Subfamily: Trochilinae

- Tribe: Lampornithini

- Genus: Heliomaster

The plain-capped starthroat is in the ‘mountain gems’ group of hummingbirds (Tribe Lampornithini), with 18 species and 7 genera. Of the four total species in the genus Heliomaster, the plain-capped starthroat is the only one found in North America; the other three species range from Mexico to South America.

The genus name, ‘Heliomaster‘, means ‘sun seeker’. This species was named by Adolphe Delattre, a French ornithologist, in 1843. There are three subspecies of plain-capped starthroat: H. c. constantii, H. c. pinicola, and H. c. leocadiae, that have slightly different colouration and ranges, but intermix at contact zones.

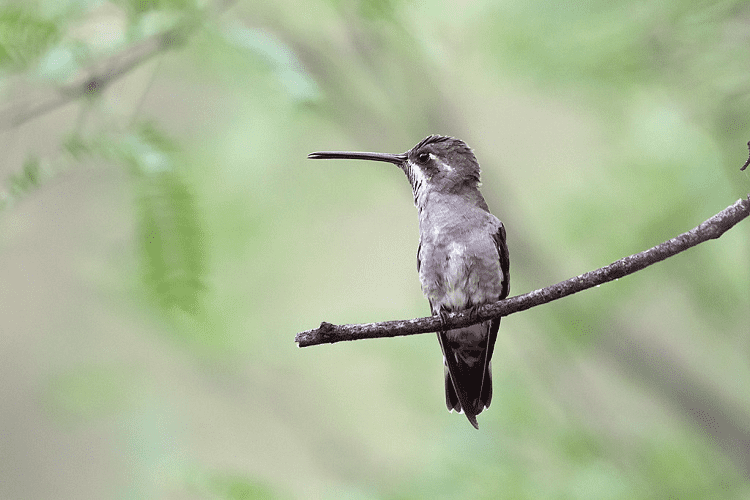

How to Identify Plain-capped Starthroat

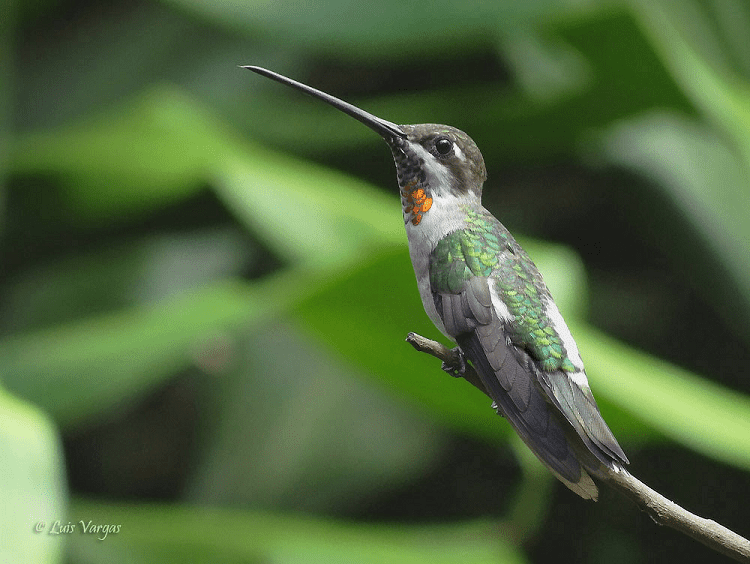

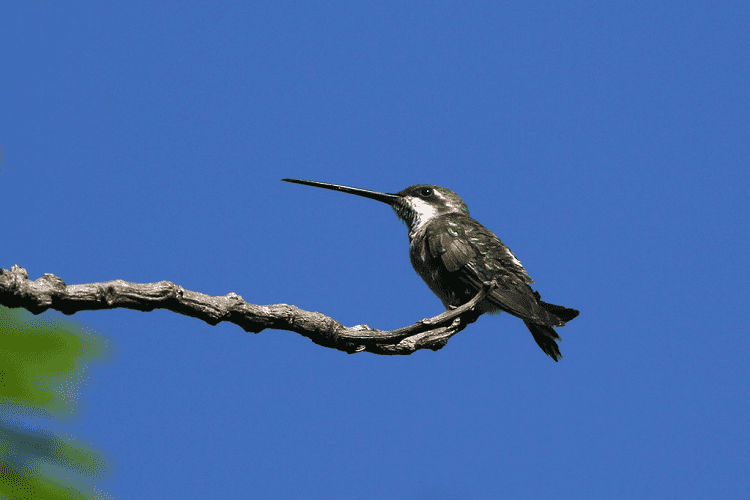

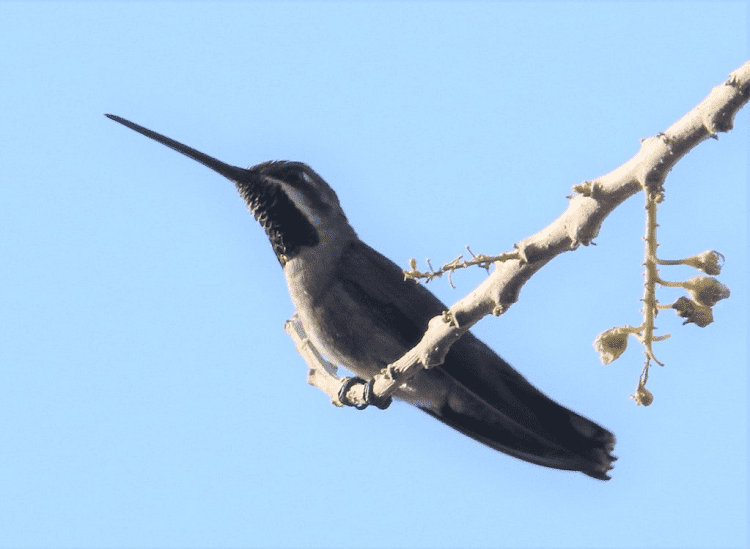

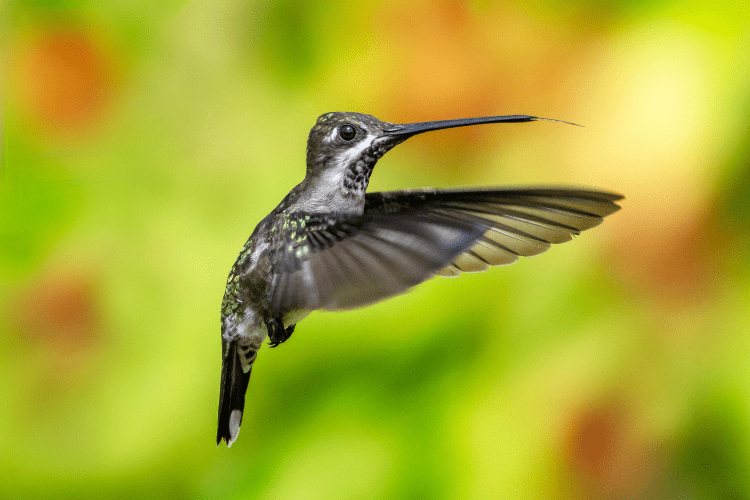

This is one of the plainer hummingbirds. It does have a metallic throat but that’s about it for flashy color. They are fairly large, measuring 11-13 cm long and weighing 7.2-7.4 g. They have a very long, straight black bill (average 3.5 cm long).

The most striking feature of plain-capped starthroats is the combination of a white streak behind their eye and a wide white malar stripe (moustache) that frames a dusky patch extending down from the eye. Overall, they have a metallic bronze-green head, wings, and back, with gray underparts.

They have two other white streaks – a wide irregularly-shaped white streak on the lower back/rump, and a white line down the middle of their belly. Their chin is gray and their throat (gorget) is metallic red in sunlight – like all hummingbirds, the throat feathers are reflective and so appear dark without direct light.

The upper half of the tail is bronze-green, the lower half is dark, and there is a white spot on the tip of each feather except for the center two feathers. Juveniles are overall duller and have gray throats.

The sexes are either identical in adults or very close to being so, as often female hummingbirds are slightly duller in color than the males, and this may be the case for plain-capped starthroats as well.

The above description refers to the subspecies H. c. constantii. The subspecies H. c. leocadiae has paler underparts and its throat patch is more pink than red. H. c. pinicola has the palest underparts and a smaller red throat patch, and as the northernmost subspecies it is the one that can occur in North America.

Where Does the Plain-capped Starthroat Live: Habitat

Plain-capped starthroats like forests, but use open areas as well as long as there are trees for perching and flowers for food. The many types of semiarid forests they live in include the edges and interior of mature forests, thorn forest, gallery forest, scrublands, human-disturbed and secondary forest, and open areas with scattered trees.

This species generally occurs below 1,000 m in Costa Rica but has been recorded as high as 1,696 m, and it is unclear whether this represents seasonal migration, vagrants, or land-use changes – yet another example of how little we know about this species.

Plain-capped Starthroat Diet and Feeding

Like all hummingbirds, plain-capped starthroats primarily drink nectar. They are a generalist, utilizing the flowers of several plant species, which is also reflected in their generalist forest habitat use.

They have even been recorded feeding on fruit (specifically, Cephalocereus maxonii and Stenocereus eichlamii). Like many hummingbirds they will also catch small insects while flying, a behavior termed ‘hawking’, and by gleaning insects off of plants.

Plain-capped Starthroat Breeding

These birds are polygynous, meaning males mate with multiple females. There is no specific information on courting or mate choice in plain-capped starthroats, but based on other hummingbirds, it is likely that the male is only involved in mating.

In other species, the males have a courtship flight that includes vocalizations to attract females, but the specific sequence and pattern has not been reported for this species. It is probable that the female is solely responsible for nest site selection, nest building, incubation, and feeding the nestlings, as is the case for most hummingbirds.

Plain-capped Starthroat Nesting

There is almost no information on nesting, with only a single description published. It describes a nest that is similar to what most hummingbird nests looks like, with bark and lichen on the outside and softer plant material on the inside.

The single description of nest placement said it was located near the end of a branch, high up in a tree, and was exposed.

An exposed nest is unusual in hummingbirds and, in fact, is unusual in most small birds, as nestlings are very vulnerable to predators and harsh weather, especially when the female is off foraging (hummingbirds, with fast metabolism, have to forage often).

Thus the description of nest site placement should be viewed with caution as it is likely not accurate for most nests of this species.

Plain-capped Starthroat Eggs

There is no information on eggs, incubation, or nestlings, so we’ll make some inferences based on what other hummingbirds do. Most hummingbirds lay two white eggs, and there is no reason to think plain-capped starthroats are any different.

Incubation for hummingbirds ranges from 11-21 days, and since plain-capped starthroats are on the larger side for hummingbirds, they likely have an incubation period on the slightly longer side – perhaps in the range of 16-18 days.

The nestling period is typically about two weeks, so we’ll assume plain-capped starthroats incubate for around that length of time until the young are independent.

Plain-capped Starthroat Population

Plain-capped starthroats commonly occur along the Pacific slope from northwestern Mexico to Costa Rica. H. c. pinicola, the northernmost subspecies, also strays to Arizona, mainly along the Sierra Madre Occidental range, where it was first recorded in 1969 and is now being seen almost annually during the summer (May-October).

However, there are no breeding records in North America, and so they are classified as a vagrant, not a breeder. Whether they strayed into the United States prior to 1969 and just weren’t noticed, or it was harder to get documentation (such as photos) in the early half of that century, or this is truly a recent range extension, is unknown.

H. c. pinicola is normally found in northwestern Mexico from Sonora to Jalisco. They may be more common during the summer in Sonora, with some individuals moving to other areas in the winter, but generally, they are not considered a migratory species.

They are vagrants in Oaxaca, with the first record occurring in 2001. Again, information on migration and which sightings are rare vagrants or true movement is up for debate due to the lack of substantive data.

H. c. leocadiae is found in southwestern Mexico and western Guatemala. H. c. constantii is found from El Salvador through Honduras and Nicaragua into northwestern Costa Rica.

These are general ranges for each subspecies, as they mix where they meet, and the subtle color differences among the subspecies means that only those that are very familiar with each subspecies would be able to tell them apart.

Is the Plain-capped Starthroat Endangered?

No, they are not listed as endangered. They have a large range, and though it is unclear whether their population is declining, they are listed as Least Concern. There are no obvious human-caused disturbances to this species.

Plain-capped Starthroat Habits

Most hummingbirds are very territorial around food resources. However, plain-capped starthroats are less territorial than most species – except perhaps males during breeding, during which time they may defend a more defined territory – as they will follow a route between low-density flowering patches (termed ‘traplining’) instead of defending a single patch.

Plain-capped starthroats make a few different calls. The most frequent is a soft and melodious but high-pitched slurred tseep or cheek or a sharp, fairly loud peek, in addition to giving a high-pitched twitter during chases. Their song is described as a series of sharp and varied chips.

Plain-capped Starthroat Predators

There are no documented predators. Hummingbirds are fast and hard to catch; their chicks are susceptible in the nest, as is true of most birds, but there are few animals capable of catching an adult.

Plain-capped Starthroat Lifespan

There is no information on how long individuals of this species live. Most banding stations don’t band hummingbirds (they are delicate to handle), and band recaptures are the best way to learn about longevity in the wild.

An average estimate, based on other species, would be around 3-5 years, but a similarly-sized hummingbird lived in the wild to an age of 12 years, and so plain-capped starthroats could conceivably live up to a dozen years.

FAQs

Answer: This refers to the gorget (throat) pattern of some species in this genus. However, to me, their throat feathers don’t look any more star-like than other hummingbird species.

In particular, for this species, the metallic red of their throat can be hard to see without perfect lighting, making them a relatively dull-looking hummingbird most of the time.

Answer: Yes, the plain-capped starthroat is also known as ‘Constant’s starthroat’ and ‘pine starthroat,’ though it’s unclear where the latter common name came from.

Answer: The reasons are unclear. They likely followed the Sierra Madre Occidental range into Arizona, as that is where the sightings cluster, but why they have moved north recently is not known.

Conclusion

Plain-capped starthroats are a relatively understudied species, with no information on many aspects of their basic biology.

They are not a secretive bird and are found in many types of forest habitat along a fairly large range in Mexico and Central America, so it’s a little surprising that so little is known about breeding, nesting, foraging ecology, life span, movement, or population threats.

As a biologist with over a decade of experience in different biological systems, I want to go out right now and study them. I hope others take on this task so we can learn about species like this before it’s too late.

Research Citations:

- Arizmendi, M. d. C., C. I. Rodríguez-Flores, C. A. Soberanes-González, and T. S. Schulenberg (2020). Plain-capped Starthroat (Heliomaster constantii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.plcsta.01

- Brinkley, E. S. 2005. Madrean Summer. North American Birds. 59:552-558.

- Brooks, P., & Gillen, J. M. (2006). Sugar concentrations, hummingbird aggressiveness, and community composition in Monteverde, Costa Rica. Tropical Ecology Collection (Monteverde Institute). 522.

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/tropical_ecology/522 - Bustamante-Castillo, M., Hernández-Baños, B. E., & Arizmendi, M. D. C. (2020). Hummingbird-plant visitation networks in agricultural and forested areas in a tropical dry forest region of Guatemala. Journal of Ornithology, 161(1), 189-201.

- Flesch, A. D., Warshall, P., & Hadley, D. (2009). Breeding, migratory, and wintering birds of the Northern Jaguar Reserve east-central Sonora, Mexico. Report to Northern Jaguar Project and Naturalia AC.

- Forcey, J. M. (2002). Notes on the birds of central Oaxaca, Part II: Columbidae to Vireonidae. Huitzil. Revista Mexicana de Ornitología, 3(1), 14-27.

- Sandoval, Luis, Daniel Martínez, Diego Ocampo, Mauricio Vásquez Pizarro, David Araya-H, Ernesto Carman, Mauricio Sáenz, and Adrián García-Rodríguez. “Range expansion and noteworthy records of Costa Rican birds (Aves).” Check List 14 (2018): 141.

- Stiles, F. G., & Skutch, A. F. (1989). Guide to the birds of Costa Rica. Comistock.

- Wendelken, P. W., & Martin, R. F. (1988). Avian consumption of the fruit of the cacti Stenocereus eichlamii and Pilosocereus maxonii in Guatemala. American Midland Naturalist, 235-243.

- Williamson, S. (2001). A field guide to hummingbirds of North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Wolf, L. L. (1970). The impact of seasonal flowering on the biology of some tropical hummingbirds. The Condor, 72(1), 1-14.

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: