- Amethyst-throated Mountain-Gem Guide (Lampornis amethystinus) - November 24, 2022

- Best Martin Bird House Guide - November 14, 2022

- Best Millet Bird Seed Guide - November 9, 2022

We often hear the term “a murder of crows,” but do you know what any other groups of birds are called? It seems unfair that crows get all the attention for having a unique group name. In the case of hummingbirds, these vivacious and quick gems are referred to using very endearing terms when gathered in groups, such as:

- A bouquet of hummingbirds

- A glittering of hummingbirds.

- A tune of hummingbirds

- A shimmer of hummingbirds.

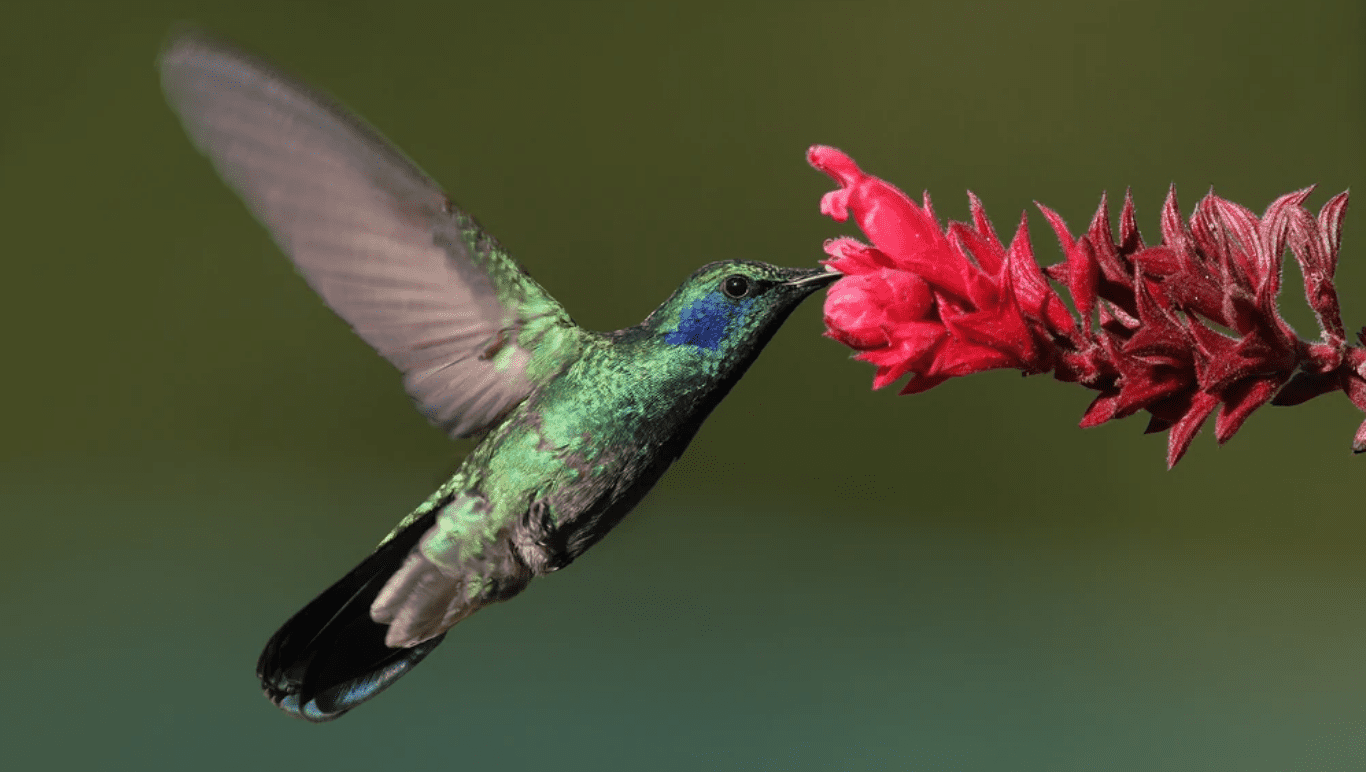

That last one is definitely my favorite. When the sun dances across the iridescent feathers of multiple hummingbirds, it’s hard to feel anything other than joy. When looking at a Mexican Violetear, you’ll immediately understand why such beautiful words are used (sorry, crows).

Hummingbirds are absolutely fascinating for so many reasons. They are some of the smallest birds, yet they still have some significant and impressive characteristics and advantages. Did you know hummingbirds have the largest brain, heart, breast, and flight muscles in proportion to their body size than any other birds? These muscles and organs make up 30% of their total body mass. Additionally, they can rotate their wings in a complete circle. This adaptation allows hummingbirds to fly forward, backward, up, down, sideways, or simply hover, effortlessly suspended in mid-air.

It is commonly shared that hummingbirds do not have a sense of smell, but recent studies at the University of California show that they actually do have a sense of smell, which aids them in many ways.

We have so much to learn and marvel at when it comes to hummingbirds, and the Mexican Violetear is just as remarkable for all these reasons and more.

Taxonomy

Like all other hummingbirds, swifts, and treeswifts, this vibrant and beautiful hummingbird belongs to the order Apodiformes. The name Apodiformes originates from the words “a pous,” meaning “footless” in Greek. These birds’ tiny and almost invisible feet are only spotted when they are perching. This is the primary purpose of their feet, rendering them dangling ornaments the rest of the time. Luckily, their feet are very small and do not impede the bird’s ability to hover, dive, and whirl around at fast speeds.

The Mexican Violetear, a member of the family Trochilidae with nearly 400 other species of hummingbirds, is further classified into the genus Colibri. This genus is home to five different species of violetears. The Mexican Violetear was formerly known as the Green Violetear. In 2016, the Green Violetear was separated into two species: the Mexican Violetear and the Lesser Violetear. A few of the species below appear very similar to the Mexican Violetear, so take note of their distribution range to confirm any sightings you might be lucky enough to log!

- Brown Violetear (Colibri delphinae) – Found in Mexico to northern and western South America.

- Lesser Violetear (Colibri cyanotus) – Found in Costa Rica, Panama, and the Andes north of Bolivia.

- Sparkling Violetear (Colibri coruscans) – Found in the Andes north of Argentina.

- White-vented Violetear (Colibri serrirostris) – Found in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay.

How to Identify a Mexican Violetear

Anytime I see a gorgeous hummingbird, I reflect on how lucky we are to exist in the same world with stunning little creatures like these busy birds.

Mexican Violetears, while extremely vibrant and jewel-like, can blend easily with their surroundings when in subtropical areas. In other habitats, this bird is easy to single out.

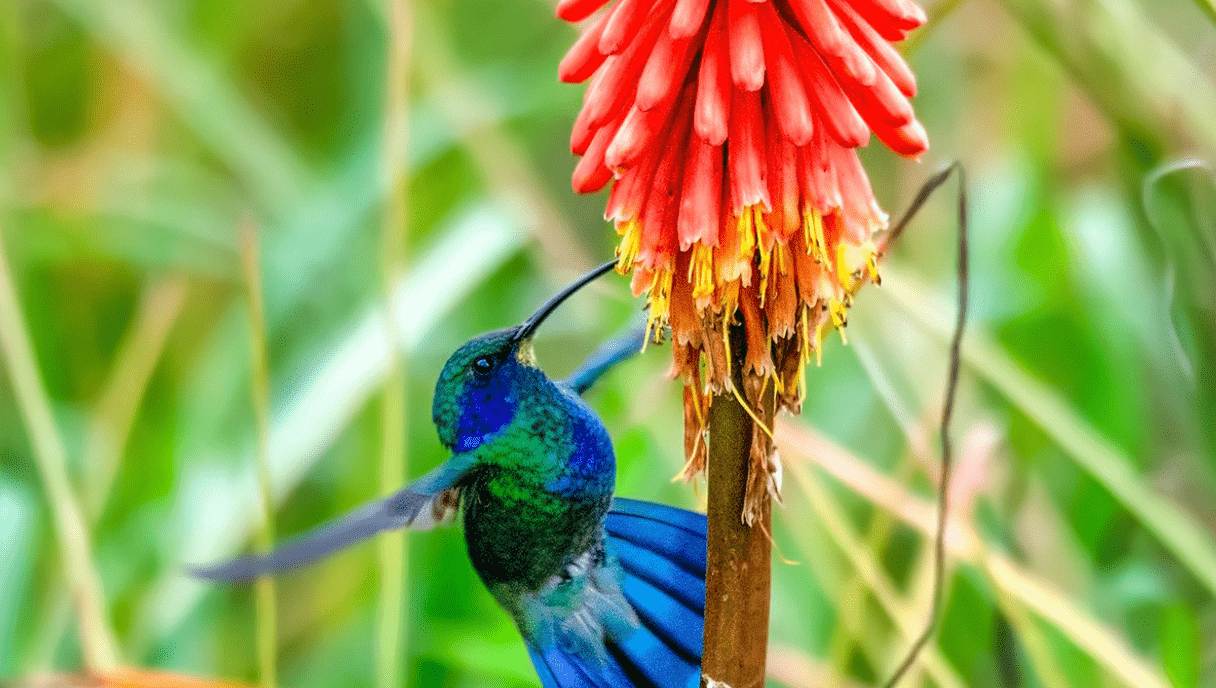

Nothing short of captivating, with a dark glimmering emerald body, dark blue-violet ears, and breast patches, the Mexican Violetear’s throat feathers look like turquoise sequins as this bird hovers effortlessly in the air.

The Mexican Violetear received its name from a sizable violet spot on the upper breast and a Violet-blue band across its chin that typically connects with the violet-blue patches on the ear.

Their small black eyes stand out against their vibrant violet ear patch and perfectly complement their long, slender, and slightly decurved bill. Tails are square, blue-green, and feature a black band. On average, they are 4.25 to 4.5 inches in length, which makes them medium-sized for a hummingbird.

Males and females have a similar appearance. The male will be larger in size and have more vibrant coloration.

Juveniles are easily distinguished from adults due to their buff crown, nape, and underpart. Rufous edging along the feathers is common.

Calls and Vocalization

Hummingbirds are no joke to spot, especially in a misty forest. Listen for the Mexican Violetear’s jerky song. It’s a very robust “tsu-tzeek.” Their dry call is a quick “chut” sound.

Where Does a Mexican Violetear Live: Range and Habitat

The Mexican Violetear is a species that occurs from southern Mexico to Nicaragua. While rare, sightings have been recorded in the southern, central, and eastern regions of the United States, primarily in Texas. In Canada, sightings in Alberta and Ontario have been reported.

The Mexican Violetear is a bird of variety, enjoying semi-open areas, trees with scrub, highlands, and mountains. In South America, their chosen habitat is subtropical forests. It is most frequently recorded at altitudes of 3,900 to 7,500 feet but has been seen as low as 1,600 feet.

This small bird thrives in tropical montane cloud forests, which are moist evergreen forests, either tropical or subtropical, located in a mountainous region with low-level cloud coverage. If you read that and thought, “yes, take me there,” you’re my kind of human. It sounds simply magical, but with a name like “cloud forest,” it’s hard not to. The Sparkling Violetear also lives in cloud forests; you may see these two birds together.

The Mexican Violetear may also move about various mountain ranges, taking up residence in clearings and along the edges of forests.

Mexican Violetear Diet and Feeding

Like other hummingbirds, the Mexican Violetear enjoys many insects, usually fruit flies, mosquitoes, and gnats. They are also nectar fanatics. Flowers attract these birds with their fragrance and vibrant colors. Flowers may be on trees, shrubs, or epiphytes, such as orchids, tillandsias, and other common plants found in humid tropical forests.

Hummingbirds seek out nectar with a sugar content of 10% or higher. Their rapid metabolisms demand that they consume twice their body weight in nectar each day which typically requires feedings every ten to 15 minutes. They can visit around one thousand flowers or more in a day. Something has to sustain that high heart rate!

Red tubular flowers are a crowd favorite with their easy-to-access shape and high sugar content. The visit is short, with 13 licks per second, and nectar is consumed instantly. With such a demand for calories, Mexican Violetears will stay close to this popular food source to protect the flowers from other hungry hummingbirds.

While sucrose is important to keep the birds moving at high speeds, it has very little nutritional benefit. Other food sources like insects give hummingbirds the vital nourishment needed to survive. While hovering or in flight, insects are plucked from leaves, branches, the ground, or even stolen from spider webs.

Male hummingbirds locate beneficial feeding areas with plenty of insects and use their aggressive habits to ward off larger insects who also wish to feed on nearby insects. They must also defend this feeding territory against other male hummingbirds.

When nesting, a female aims to collect around two thousand insects in a single day which she will regurgitate directly into the bellies of her babies.

The Coevolution Of Flowers and Hummingbirds

Hummingbirds are efficient pollinators that highly benefit flowers in return for taking a drink of the flower’s sweet nectar. When a hummingbird stops by for nectar, it gets the pollen from the male parts of a flower on its body and bill. As the bird makes its way to the next flower, it rubs the pollen on the female parts of that flower. This advantageous relationship led to an evolutionary change in both flowers and hummingbirds.

When we see hummingbirds with different shaped bills, long and straight, wider and curved, etc., these are perfect examples of the co-evolution that occurred. Their bills are shaped differently to accommodate feeding from specific flowers. Thus, these flowers make nectar custom for hummingbirds. This nectar has a high sugar content that is the perfect fuel for busy hummingbirds. The flower’s tubular shape makes it hard for bees and other animals to access the nectar.

Mexican Violetear Breeding

Hummingbirds aren’t romantics. They prefer their solidarity for most of their lives. The only time they associate together meaningfully is during the breeding process.

Male hummingbirds will climb 60 feet or more and dive in a swooping formation to attract a female. This performance is repeated three or four times. Once the female has chosen a male to copulate with, it’s au revoir. The males will often mate with several females, and the females may also mate with other males.

The female is entirely responsible for selecting the nesting location, building the nest, and raising the young. No big deal, piece of cake! She may choose to nest within the male’s territory, which offers some protection since he will continue to defend it aggressively.

Some biologists suggest that female hummingbirds forbid the males from coming near nesting sites because the male’s vibrant coloration may lure predators to the nest. Nesting within a male’s territory means that the female must only worry about one male in the area. So while you may view the male hummingbird as a deadbeat dad, the females seem to hold most of the power and do all the decision-making.

Mexican Violetear Nesting

The female constructs a nest that is a delicate and small cup located on a horizontal branch, drooping twig, or rootlet. Ideal nesting locations are along the edge of the forest or streamside. She may also choose to build her nest in a shrub or bush.

Nesting materials such as down, grass, moss, spiderwebs, and lichen are collected to build a finely formed and deep cup that is durable, soft, and elastic. The nest will be able to expand as the nestlings grow and demand more room. The nest is covered in lichen, moss, or bark to camouflage the nest from predators.

Mexican Violetear Eggs

A standard clutch of two small white eggs is laid, and the female begins the incubation process, lasting 14 to 18 days. Again, this is the sole responsibility of the female, and the male is only purposeful for mating and defending the surrounding area.

Once hatched, the female collects a variety of insects that she regurgitates into the mouths of the chicks several times a day. She uses her bill to deliver the food directly to the stomaches of the young birds.

The brooding period for hummingbirds is extremely short compared to other species of birds. The mother will begin to leave the chicks alone after one to two weeks. The chicks must fend for themselves, which leads them to leave the nest at just ten days old.

Mexican Violetear Population and Lifespan

According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, there is insufficient research on the Mexican Violetear, and the global population and average lifespan are unknown, but biologists believe that populations are healthy and the average lifespan is about twelve years.

Is The Mexican Violetear Endangered?

It is believed that the overall population of the Mexican Violetear is large, and there are no signs of population decline. This hummingbird is rated as a species of Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.

Mexican Violetear Predators

Hummingbirds, while fast, still fall prey to a variety of predators. Those among their worst enemies include:

- Cats, both domestic and feral.

- Praying mantises

- Orb weaver spiders

- Birds of prey (hawks, kestrels, merlins)

- Owls

Predators that raid nests and eat young and eggs include:

- Squirrels, rats, and chipmunks

- Jays, crows, and ravens

- Snakes and lizards

The process of camouflaging the nest helps deter predators, but it does not always prove successful.

FAQ

Answer: Violetear hummingbirds live in Central and South America. You’re likely to see one of these birds along mountain ranges from Mexico to Nicaragua.

Answer: Just like most hummingbirds, the Mexican Violetear hunts down nectar from flowers, trees, and shrubs. A main source of nectar is the coffee-shade Inga. They also consume a variety of small insects to get nutrients that nectar does not provide.

Answer: Hummingbirds have been known to represent the end of challenging times in your life. If a hummingbird appears during a particularly stressful time, they are believed to signify that things will get better soon.

Answer: Hummingbirds spend most of their time looking for nectar and insects. They need to eat or drink every 10 to 15 minutes to maintain their high metabolism. They will visit nearly one thousand flowers daily and may consume up to two thousand insects.

Conclusion

If you’re having trouble discovering information on the Mexican Violetear hummingbird, try looking for resources on the Green Violetear. Many old sources have not been updated to reflect the species split.

As you wander through a cloud forest in South America, I hope you find yourself in a clearing of Mexican Violetears. It sounds pretty idyllic, but the good news is that it exists in our world!

Research Citations

- What Bird: Mexican Violetear Guide

- Audubon: Mexican Violetear Guide

- Biodiversity Heritage Library: Green Violetear

- A guide to the birds of Mexico and northern Central America by Steven Howell

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: