- Common Woodpeckers in Missouri Guide - September 13, 2023

- Iconic Birds of New Mexico Guide - September 13, 2023

- Red-breasted Sapsucker Guide (Sphyrapicus ruber) - February 27, 2023

Few North American birds inspire the mix of hope, sadness, and awe quite like the magnificent Ivory-billed Woodpecker, which once inspired people to yell out “Lord God, what a bird!” when it flew overhead – a sight that most of us will never get the chance to see. To talk about the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is to confront tragedy and regret – there is a lesson to be learned from this bird that we most likely lost to extinction long ago.

A few do hold out hope that the Ivory-billed Woodpecker – the largest woodpecker in North America and the third largest in the world – is still out there. On the off chance that it is, this guide will help you locate and observe this extremely rare bird and will show you how to distinguish it from the similar but more common Pileated Woodpecker.

Should you be the one to find an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, in addition to being the luckiest person on Earth, there is a hefty reward! Keep reading to learn more. Otherwise, let this guide tell the story of a beautiful and unique species whose extinction we were tragically too late to prevent – and let us use it to help keep the birds we still have safe from the same fate.

Taxonomy

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is a member of the order Piciformes, which includes the tree-dwelling woodpeckers, toucans, honeyguides, and barbets in its nine families. It is further classified into the order’s largest family, Picidae, which includes woodpeckers, sapsuckers, piculets, and wrynecks. Within the Picidae, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker falls under the subfamily Picinae, which includes the true woodpeckers.

There are 204 species of true woodpecker in the subfamily Picinae divided into 33 genera. They occur worldwide, mainly in forested environments, but are not found in Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, on most islands, or in the polar regions.

All woodpeckers are adapted for life in the trees, with zygodactyl feet – in which two toes point forward and two backward – and large claws that allow them to cling to tree bark while foraging. They also have stiff tail feathers, which they use to brace themselves against trees for stability.

As their common name suggests, woodpeckers are expert carpenters. They have large, powerful specialized bills that allow them to chisel into wood when foraging for their preferred insect prey. They also have many special modifications in their skulls, brains, and muscles that allow them to absorb the shock of repeatedly pounding their heads into hard wood. Another adaptation that comes in handy is their long extendable barb-tipped tongue, which they insert into openings to capture prey.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is one of 11 species in the genus Campephilus, which means “grub lover” in Latin. Woodpeckers of the genus Campephilus are found exclusively in the Americas, with all but the Ivory-billed Woodpecker occurring in Mexico, Central America, and South America.

In addition to feeding on grubs, Campephilus woodpeckers are large crow-sized birds that produce a characteristic double knock sound by drumming on trees which serves as their song. Of the 11 species, two are likely extinct – the Ivory-billed Woodpecker and its Mexican cousin, the even larger Imperial Woodpecker.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker was first described by the English naturalist Mark Catesby in 1731. Owing to its large size and distinctive appearance, it is a bird of many common names, including log cock, Indian hen, log god, Poule de Bois, kent, Tit-ka, wood hen, Lord God Bird, kate, and the Holy Grail Bird. In fact, Woody Woodpecker was modeled after an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, frequently giving his name as Campephilus principalis in the cartoon.

Taxonomy at a Glance

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Aves

- Order: Piciformes

- Family: Picidae

- Subfamily: Picinae

- Tribe: Campephilini

- Genus: Campephilus

- Species: Campephilus principalis

How to Identify the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

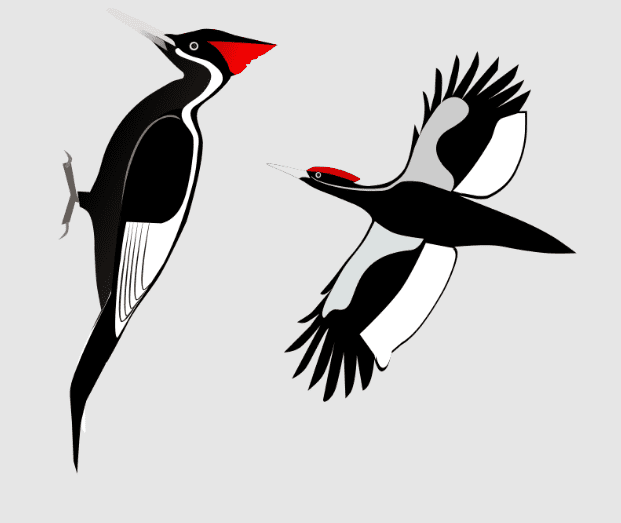

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are the biggest woodpeckers in North America. They are fairly unmistakable – but only if you get a good look, which few of us do. They are often confused for the smaller and more common Pileated Woodpecker.

Adults

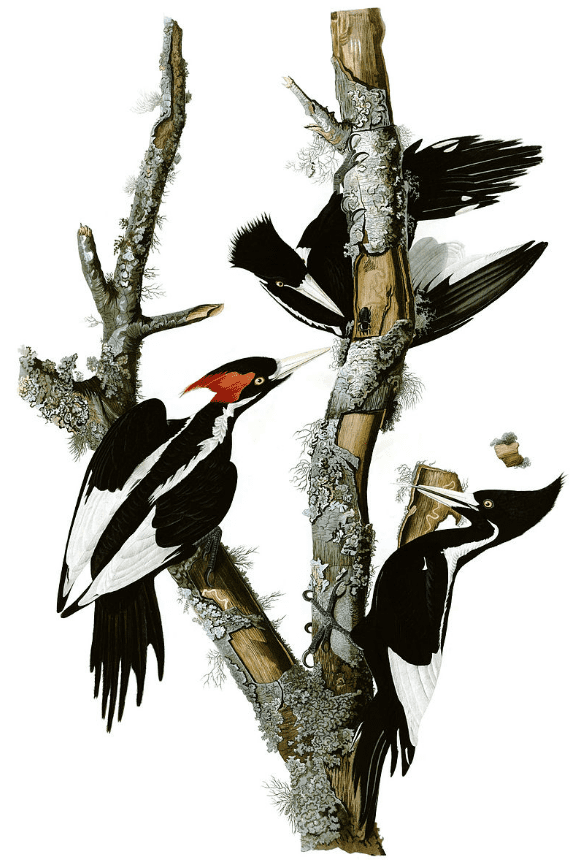

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are large crow-sized birds with trim bodies, relatively long necks, and long tails. They measure about 18 to 20 inches from head to tail with an over two-foot wingspan. Alive, they likely weigh around one to one and a half pounds.

They are predominantly black, and their plumage is shiny with a blue or purple iridescence. They have two white stripes that extend from the sides of their necks down their backs. When perched, they have large white patches on their wings that form a triangle shape on their lower backs.

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers have black faces and chins marked by bright yellow eyes, which make their dark pupils easily visible. As their name suggests, they have large, straight, creamy white to yellowish-ivory bills that measure almost three inches in length. Their bills are flattened side to side when viewed from above or below, and are quite similar in shape to a chisel. Their legs and feet are light gray, each toe ending in a large claw necessary for gripping trees.

Like many woodpeckers, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are sexually dimorphic, that is, males and females look different. Male Ivory-billed Woodpeckers have a large red crest that curves backward, while females have a black crest that curves forward.

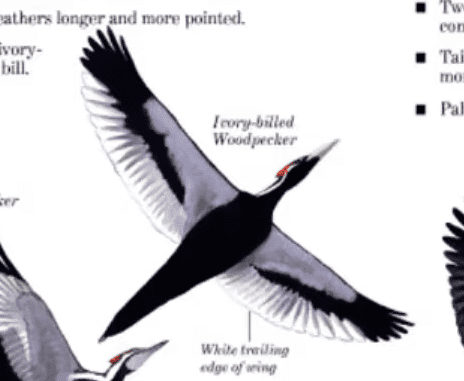

In flight, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers appear to have a black stripe extending through the middle of each wing when viewed from below, with both the shoulders and wingtips appearing bright white. The trailing edge of the wings is white when viewed from above or below. Ivory-billed Woodpeckers fly in a straight line with quick, shallow wingbeats when traveling a long distance, looking similar to a flying duck. When moving from tree to tree, they perform a graceful swoop.

Immature Birds

Unlike most baby birds, young woodpeckers are not covered in down and instead begin growing feathers at just a few days old. Nestlings, therefore, look similar to adults but have shorter tails and less-defined features.

Juvenile Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are browner than adults and all, even the males, have short, scruffy black crests. Their eyes are brown and their bills are brighter white rather than the yellow-tinged ivory color of adults.

Subspecies

There are two subspecies of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Campephilus principalis principalis occurs in the southeastern bottomland forests of the United States. It is larger in size, with a larger bill. The two white stripes do not extend very far up its neck, ending in the cheek region.

Campephilus principalis bairdii occurs in the mountain pine forests of Cuba. It is smaller than C. p. principalis and has a slightly smaller bill. The white stripes extend well onto its face, almost reaching the bill. Some consider this to be a separate species and genetic studies are currently in progress.

Similar Species

The only bird that could be confused with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in its natural range is the much more common Pileated Woodpecker. Pileated Woodpeckers are also large red-crested woodpeckers of the forest, and even experienced ornithologists have confused them for Ivory-billed Woodpeckers when only afforded a brief or partial glimpse.

While it may be hard to tell without a direct comparison, Pileated Woodpeckers are smaller by 10 to 20%. But the best way to tell the birds apart is to look at their plumage and bills. Pileated Woodpeckers have gray to silver bills. Their plumage is brownish black and lacks the colorful blue and purple tints of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

They also have pure black backs that lack the two white stripes and white wing patch triangle. Pileated Woodpeckers have white chins, while the Ivory-billed Woodpeckers have an all-black face. In flight, Pileated Woodpeckers have white shoulders and armpits when viewed from below, but the trailing edge of the wings is black when viewed from above and below.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Vocalizations and Sounds

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers have four distinct vocalizations that we know of. Most of this knowledge comes from the recordings and observations of Dr. James T. Tanner, who studied some of the last known Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Louisiana from 1935 to 1939.

Calls

The main vocalization of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is a short nasally “kent,” “yank,” or “hant” call that has been described as having the tinny qualities of a toy trumpet or clarinet. This call is often given singly or as a two-note “kent-kent” call and is mainly issued while the bird is foraging. This call is not very loud, especially compared to the vocalizations of other woodpeckers, and can only be heard about a quarter of a mile away.

Agitated Call

The standard “kent” calls accelerate, become higher pitched, and are sometimes doubled in a repeated series as “kent- kent, kent-kent” when the birds are agitated.

Conversational Call

When communicating within a pair or with young at the nest, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers issue a three-note “kent-kent-kent” call.

Drumming

Like most woodpeckers, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers create loud drumming sounds that resonate through the forest by striking trees with their bills. Woodpecker drums are unique to the species and serve the same function as songs in other birds – to attract mates and announce territories.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker, like other members of the genus Campephilus, performs a two-note “double knock” drum “song” in which the first note is loud and the second note is slightly softer. They also occasionally issue a single-note drum.

Where Does the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Live?

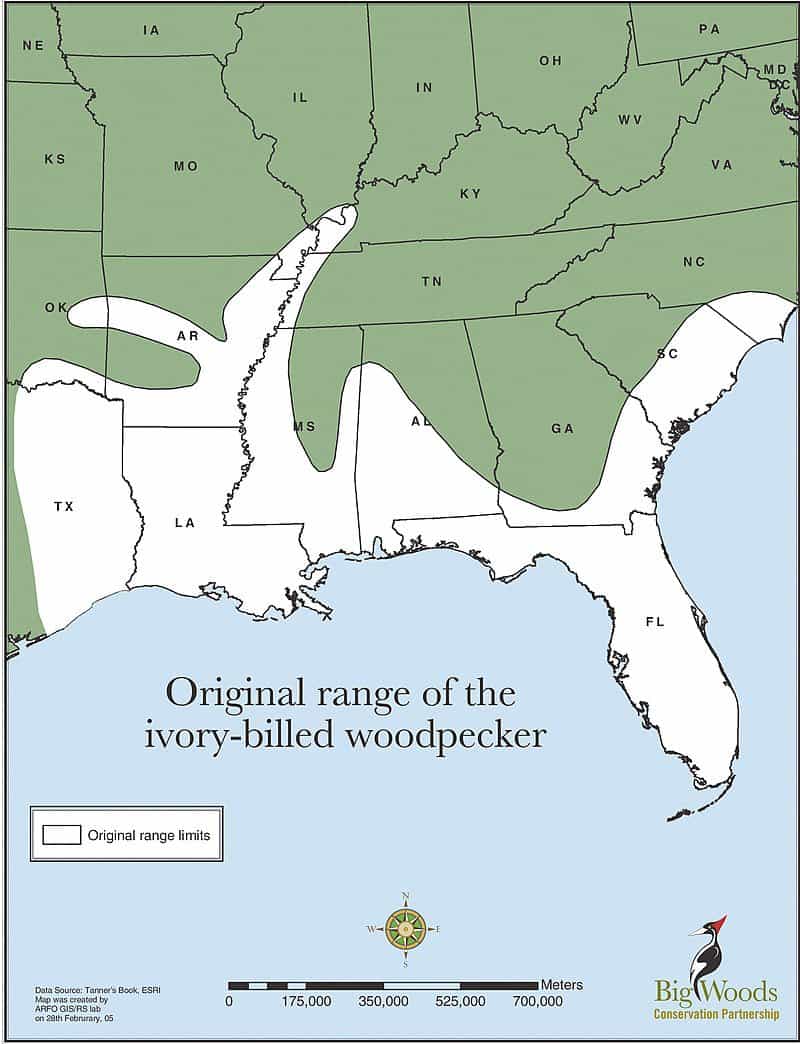

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers live in swampy bottomland forests of the southeastern United States.

Range

Before the deforestation of most of the East Coast and Southeast, it is estimated that the Ivory-billed Woodpecker could be found across much of the southeastern United States from eastern Texas to North Carolina and from southern Illinois to Florida. The northernmost account of the species was in southern Kentucky. This historical range is a best guess based on specimens, remains, habitat types, and compelling eyewitness accounts, as studies of the species began after it was already declining.

Currently, it can be found along the Gulf Coast and southern Mississippi River Valley in isolated patches in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.

It can also be found in Cuba, although it is now confined to the mountain pine forests.

Habitat

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker lives in extensive undisturbed bottomland hardwood swamp forests, showing a preference for mature and old-growth forests. Based on past sightings and studies, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker often occurs in forests containing bald cypress, American elm, sweetgum, Nuttall’s oak, sugarberry, water oak, green ash, and willow oak.

Historically, they could be found in upland longleaf pine forests but by 1891 they were confined to the lower elevations from sea level to 100 feet elevation. More recently, they occur anywhere there are large sections of open forest with big trees in lowland pine forests, cypress forests, swampy forests along rivers, and, in Cuba, in temperate pine forests.

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers require a mixed habitat that features a combination of wet and dry areas, as they forage for beetle larvae in areas with sections of standing dead trees killed by fire, flooding, or other causes but nest and roost in large trees.

In the past, they would often travel from the swamps to the pine forests to forage or would feed in recently burned or flooded areas before returning to their roosts in the evening. It is estimated that a single pair of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers requires at least 17 square miles of uninterrupted forest to find enough prey.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Migration

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is not migratory, and nests in the same general area year to year. They are, however, nomadic, and travel to find good foraging areas with many stands of recently killed trees.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Diet and Feeding

Like most woodpeckers, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker feeds almost exclusively on insects but does supplement its diet with fruits and nuts.

Beetle Larvae

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker’s preferred prey is the large wood-boring larva of the longhorn beetle family. They will also eat larvae of the click beetle family, the jewel beetle family, and smaller bark beetles, including the southern pine beetle.

Such beetle larvae prefer dead wood, as the water within living tree tissues drowns them. Therefore, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker seeks out stands of dead trees to hunt for them. Because these insects occur deep in the wood of trees with tightly wound bark, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is the only bird able to rip through the bark and excavate to reach them.

Fruit and Nuts

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker also eats nuts – including pecans, hickory, and possibly acorns – as well as fruits like grapes, magnolia, poison ivy berries, hackberries, and persimmons.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Breeding

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker’s breeding season starts between January and March and ends in May. They only raise one brood per year but will start a new clutch if the first one is lost.

Courtship

Unfortunately, not too much is known about the courtship behavior of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers as few have been lucky enough to observe them. Pairs appear to be monogamous, travel together, and most likely mate for life.

On one occasion, a pair was observed preening one another, stopping to briefly hold each other’s bills.

Nesting

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers select nest sites on trees 15 to 70 feet off the ground, with the most common nest height falling in the range of 25 to 60 feet up. Ivory-billed Woodpecker nest trees have included: red maple, bald cypress, pine, tupelo, Nuttall’s oak, bay, overcup oak, elm, hackberry, sweetgum, and possibly cabbage palm.

They prefer large living trees or trees with dead sections, usually choosing a future nest hole location right below a broken branch. This likely provides protection from the rain, shade, and extra camouflage – but the wood is usually also rotten and softer here, making it easier to work with.

Pairs then excavate the nest cavity together, creating an oval to rectangular entrance hole five to six inches tall by four to four and a half inches wide. They then tunnel up to two feet into the tree, hollowing out an elliptical cavity six to ten inches across and two to three inches tall. They do not add any lining to the nest, using whatever wood chips and sawdust is present from the excavation.

Watch a pair interacting near their nest hole in one of the only videos ever captured of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers:

Pairs do not reuse nests, instead creating a new nest cavity each year in the same area.

Eggs

Egg-laying occurs in April or May. Ivory-billed Woodpeckers lay only two to three eggs – the smallest clutch size of all woodpeckers. Clutches laid earlier in the season are smaller, while later clutches are slightly larger. Rarely clutches of up to six eggs have been observed.

The eggs are white, like those of all woodpeckers, as there is little need for camouflaged coloration in the dark tree cavity. Scientists also believe the white color helps the parents see the eggs in the dark nest. They are oval-shaped, smooth-textured, and glossy.

Incubation is thought to take about 20 days. Both parents share in incubation duties, typically trading off every two hours during the day to allow each other to forage. The male does most of the incubation at night.

Nestlings

Young Ivory-billed Woodpeckers hatch around the same time, so they are all about the same age. They are altricial, emerging from their shells naked and helpless. Both parents feed the young, and the male broods them at night and on cold days in the beginning.

As the chicks age, they start growing feathers. Unlike most birds, young woodpeckers do not have down – instead, growing true feathers right away. They fledge at five weeks old but do not fly well until they are at least seven weeks old.

The young stay with their parents for two months or more after leaving the nest and do not disperse until winter.

The most well-known Ivory-billed Woodpecker nestling was a young male named Sonny Boy, who James Tanner banded in 1938. While climbing back down from the nest hole after banding him, Sonny Boy spooked and fell from the nest tree – luckily landing in soft vegetation. Tanner got several photos with the young woodpecker before returning him to his nest hole. He grew into an adult male, and his baby pictures are now the only photos of a young Ivory-billed Woodpecker in existence.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Habits

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker likely spends much of its time on the wing, gliding from treetop to treetop, foraging over large areas.

Foraging

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers emerge from their roost holes at dawn and begin searching for food, likely traveling great distances to find just the right patch of dead trees. Mated pairs often travel together.

They are fast and agile, climbing quickly up and around trees in a series of seemingly erratic movements. They search fallen logs and tall snags for their favorite food – wood-boring grubs.

They forage by pounding and hammering recently dead trees with their powerful bills, wedging, excavating, and peeling the bark to extract their prey.

In areas with abundant prey, the birds gather in groups – some accounts describe 11 birds feeding together, with four on the same tree! They have also been observed sharing space with Pileated Woodpeckers. Since there is no evidence that they are territorial, they may be somewhat social birds.

By opening holes in dead and dying trees, the Ivory-billed Woodpecker accelerates their demise. It serves as a keystone species, opening up small patches of sunlight and keeping the forest healthy.

Roosting

In the late afternoon, Ivory-billed Woodpeckers return to their roost areas, where they sleep in their preferred roost hole night after night.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Predators

The main predator of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers is us. Humans pose the biggest threat to the birds, as we remove vital habitats and shoot them for meat and collections.

Ivory-billed Woodpeckers likely have other predators, but since they are not well studied, we can only speculate what they might be. They allegedly give a predator response to Red-shouldered Hawks and Cooper’s Hawks, so it’s likely these raptors prey on young and possibly adults, too.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Lifespan

No one knows how long an Ivory-billed Woodpecker lives. Only one was ever banded, and he likely perished when the Singer Tract was logged.

Biologists believe, based on the lifespans of other Campephilus woodpeckers, that they likely live up to 15 years – if they live at all.

Ivory-billed Woodpecker Population

The current population of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers is unknown and could well be zero. However, according to Tanner’s research, even if the population of the species was healthy, they would always be considered fairly rare due to their need for large foraging areas. Several woodpeckers may concentrate where food resources are ideal but would be scarce everywhere else within the range.

Still, there is no doubt that the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is in big trouble. The species has been declining since the late 1800s and was already considered extremely rare by the early 1900s. By the 1930s, most of its habitat had been destroyed. In 1935, Tanner and his team estimated there were only 22 to 24 birds left in the United States.

The last reliable account of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the United States was in 1944. A small number of Cuban Ivory-billed Woodpeckers were discovered in 1986, but by 1987 the birds could no longer be located.

Between 2006 and 2010, researchers from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology surveyed 523,000 acres of the southeastern United States but found nothing: no nest holes, wood chips on the ground, feathers, or trees with peeled bark. Sightings have been reported and investigated since then, but no definitive sign of the birds has as of yet been found.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology actually offers a $50,000 reward for any compelling photo or video evidence of a living Ivory-billed Woodpecker. You must also be able to lead a project researcher to the area you encountered the bird. More recently, Mission Ivory, an agency committed to finding the species, offers to pay $12,000 to anyone with information on a living Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Is the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Extinct?

Whether or not the Ivory-billed Woodpecker is extinct is somewhat of a loaded question. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the species as endangered on March 11, 1967. Even then, no birds were known to exist.

Currently, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the species as critically endangered, meaning it is at high risk for immediate extinction. The American Birding Association considers it probably extinct or extinct. Indeed, a great many ornithologists believe it is already extinct – but the formal declaration has not come just yet.

Following a five-year review in 2019, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the Ivory-billed Woodpecker should be removed from the Endangered Species List because it was likely extinct. In September 2021, the agency proposed that the species be listed as officially extinct, but offered a five-month period for comments and held a public hearing in January 2022.

In July 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced that they were extending their review period – granting the Ivory-billed Woodpecker a six-month reprieve from official extinction. While it seems like good news, the fact remains that there has not been a single confirmed Ivory-billed Woodpecker sighting in the United States for 78 years.

Why Did the Ivory-billed Woodpecker Disappear?

Several factors caused the Ivory-billed Woodpecker’s numbers to decline to possibly zero. Historically, Native Americans hunted the Ivory-billed Woodpecker for their bills and crests, which they used as decorations and to make Wawa pipes. There was even a lucrative bill trade, and Ivory-billed Woodpecker remains have been discovered far outside their natural range. While this could have lowered the birds’ numbers, the forests were intact in those times, and the population was likely stable enough to handle it.

Later, as Ivory-billed Woodpeckers became increasingly rare, taxidermists and collectors over-harvested the remaining birds, helping to put the nail in the species’ coffin. One pair was killed days after their rediscovery in Florida in the 1920s. Other collectors harvested eggs from the same pair twice in one season.

But by far, the main cause of this iconic species’ decline was habitat loss and fragmentation. Much of the southeast was logged following the Civil War, and the lumber industry only grew more lucrative as there was a push to supply materials for World War I and II. Much of the fertile swampland was also converted to agriculture.

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker survived then only in isolated patches of rare, undisturbed forest, with Tanner estimating that only 22 to 24 were left in 1935. Six to eight of those birds lived in an 82,000-acre section of old-growth forest in Louisiana known as the Singer Tract.

The most tragic chapter in the Ivory-billed Woodpecker’s history occurred in the early 1940s. Following his study, Tanner pushed for the protection of the remaining woodpeckers, specifically those on the Singer Tract, as they were the most numerous. He had also spent years observing them, and much of what we know about the species’ behavior – as well as the only videos and audio recordings of the species – comes from Tanner’s research on that small population.

But, despite efforts by Tanner, The National Audubon Society (which offered to buy the land), the governor of Tennessee, President Franklin Roosevelt, and Richard Pough (who would later help found The Nature Conservancy), the Singer Tract was logged to the ground by the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company. The last Ivory-billed Woodpecker, a lone female, was observed in a small patch of trees on what remained of the Singer Tract in 1944 when logging was almost complete.

FAQs

Question: How Many Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are Left?

Answer: It is highly likely that no Ivory-billed Woodpeckers are left. If the species is not extinct, there are probably only a few scattered birds in the wild.

Answer: The Ivory-billed Woodpecker is not officially declared extinct yet, but is most likely extinct. It experienced catastrophic population declines due to habitat loss as most of the old forests of the South were logged. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker requires huge areas of continuous forests to find enough of its beetle larvae prey to survive. Without the forests and beetles, the species cannot survive.

Answer: While both species are in the same family, look similar, and occur in the same area, there are several key differences. First, Pileated Woodpeckers are smaller. Second, they have gray to silver bills rather than the bright white bills of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Third, Pileated Woodpeckers have white chins and solid black backs, while Ivory-billed Woodpeckers have black chins, two white stripes down their backs, and white patches on their wings. In flight, the trailing edge of a Pileated Woodpecker’s wings are black rather than white as they are on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Answer: Yes, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology offers a $50,000 reward for any compelling evidence – such as a photo or video – of a living Ivory-billed Woodpecker. You must also be able to lead a project researcher to the bird’s territory. More recently, Mission Ivory, an agency committed to finding the bird, offers a reward of $12,000 to anyone with information on a living Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Research Citations

Books

- Alderfer, J., et al. (2006). Complete Birds of North America (2nd Edition). National Geographic Society.

- Baicich, P.J. & Harrison, C.J.O. (2005). Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds (2nd Edition). Princeton University Press.

- Ehrlich, Paul R. & Dobkin, David S., Wheye, Darryle. (1988). The Birder’s Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds. (1st Edition). Simon and Schuster, Fireside

- Kaufman, K. (1996). Lives of North American Birds (1st Edition). Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Sibley, D.A. (2014). The Sibley Guide to Birds (2nd Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Sibley, D.A. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior (1st Edition). Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- Tanner, James T. (2012). The Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Dover Publications, Inc.

Documentary

- Crocker, Scott. (2009). Ghost Bird. Small Change Productions, Inc.

Online:

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: