- Best Amazon Bird Baths Guide - September 26, 2023

- Best Copper Bird Baths - August 30, 2023

- Best Bird Baths Available at Home Depot - August 26, 2023

In the center of the eastern United States, Missouri lies in the Mississippi Flyway, a bird migration route for over 300 species as they move between wintering and breeding grounds.

Because of Missouri’s location, you can find some western birds at the eastern edge of their range and some southern birds at the northern edge of their range. With the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, prairie and forests, and hills and plains, diverse habitat supports a wide variety of bird species.

As an avid birder and someone who has studied avian biology for years, I always love learning about new birds. I’ve never been fortunate enough to travel to Missouri, but if I did, these would definitely be the birds I’d head out to try and find.

Bottom Line Up Front

Missouri is home to 340 species of birds. There are an additional 80 that occasionally show up and eight that no longer occur in the state. Iconic species represent the character of a place, and I whittled my list down to the ten that represent Missouri’s habitats and ecosystems and either have cool biology or a striking appearance!

I stayed away from common backyard birds with large ranges across the country. I also generally stuck with species listed as common or uncommon (the two most abundant sighting categories) so that people wishing to explore specific areas for these birds would have a good chance of sighting one.

The state bird is the Eastern bluebird, designated in 1927. It was chosen as the state bird because it was common, symbolizes happiness, is a harbinger of spring, and eats insect pests.

Bluebirds are iconic in their own way due to their food and nesting habitats. They are cavity nesters and require holes dug by other species, such as woodpeckers, to nest in. Historically, people removed dead trees, and the bluebirds lost many places where they used to nest.

Bluebirds are also aerial insectivores, and the use of pesticides decreases their food supply. In fact, insectivorous birds are declining at a greater rate than all other types of birds.

Since bluebirds need dead trees, which tend to be present in intact landscapes and need insects, which are present in healthy ecosystems, seeing breeding bluebirds is a good sign! Of course, they also readily take to nesting boxes, which has helped their population recover.

Iconic Species

Here are the ten species that I think best represent Missouri.

Greater Roadrunner (Geococcyx Californianus)

Though Missouri is not included in the range map for this species, roadrunners have been expanding their range east and north, so it is now possible to find them there.

This rare species is found in rocky areas without trees, a habitat type termed a ‘glade,’ which is similar to a desert habitat. Glades are one of the less common habitat types in Missouri, so birders will have to seek it out in the southern Ozarks.

Greater roadrunner facts:

- Size: 221-538 g

- Length: 20-21 inches

- Eggs: 3-6; can lay two clutches in a season

- Incubation: 19-20 days

- Fledging: 14-25 days

- Oldest known bird: 7 years (9 in captivity)

People may remember the Looney Tunes character by the same name. Though the cartoon version exaggerates all the traits of a real roadrunner and gets their color wrong, it still captures its essence: a leggy bird with a long tail and crest that runs along the ground.

In reality, it’s a brown and white streaky bird with a white belly and a dark brown crest. If you look closely, you’ll notice a patch of bare skin behind the eye; initially blue, it blends into a white and ends in a flare of red that is more visible when feathers are erect.

As the name suggests, roadrunners spend a lot of time on the ground; they’re not good fliers. They’ve been clocked running up to 26 mph, which is faster than most humans (except elite athletes) can run!

They eat pretty much anything they can catch, ranging from insects and spiders to hummingbirds, baby birds, mice, lizards, and snakes – including rattlesnakes and venomous scorpions.

To eat a rattlesnake, two roadrunners will often work together, one distracting it by fluttering around, the other sneaking up and grabbing the snake’s head to bash it against a rock.

Since roadrunners aren’t particularly big, they can’t swallow a long snake whole, so sometimes you’ll see a roadrunner wandering around with part of a snake sticking out of its mouth as it slowly digests.

Since desert-type environments are generally cool at night, some birds drop their temperature at night to save energy. However, it costs energy to warm up the next morning.

Roadrunners don’t have this warming cost as they use the sun to warm up passively. You can find roadrunners sunbathing in the early morning, often for 2-3 hours, and throughout the day in winter. They raise their feathers to expose black skin; black absorbs sunlight the fastest.

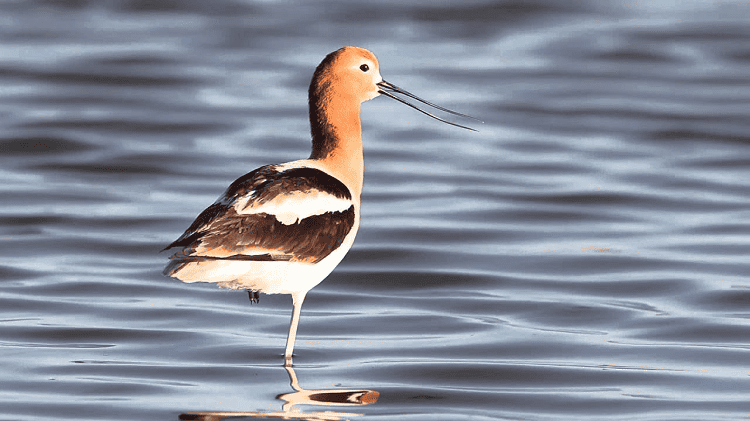

American Avocet (Recurvirostra Americana)

Avocets migrate through Missouri in the spring and fall and can usually be found singly or in small groups during this time. They prefer wetlands and wade near shore, using their bill to capture aquatic invertebrates or small flying insects.

However, they will also feed on aquatic plants and seeds. Their bill is very sensitive, and they capture invertebrates by sight and touch.

I love these birds because of their funky upturned bill. Their bold black and white wings and cinnamon head and neck (during the breeding season, light gray otherwise) are unmistakable and only add to their allure. Interestingly, females have longer bills that are more curved compared to males.

- Size: 215-476 g

- Eggs: 3-4

- Incubation: 18-25 days

- Fledging: 27 days, but young are precocial, and the family leaves the nest within 24 hours of the last chick hatching

- Oldest known bird: 15 years (21 years in captivity)

Their presence is a good sign the wetland is still functioning, as degraded wetlands don’t support enough insects to feed them. Since avocets move widely among seasons, they rely on wetlands being available on a landscape scale.

Avocets likely used to occur in the eastern states, but wide-scale wetland drainage in the 1900s, which destroyed their required habitat, combined with hunting, made these birds retreat westward.

Additionally, selenium and methylmercury contamination of wetland areas are potential issues. Efforts to halt existing wetland destruction and rehabilitate and restore degraded wetlands will help ensure this species and others that rely on intact wetlands will continue to grace our landscape.

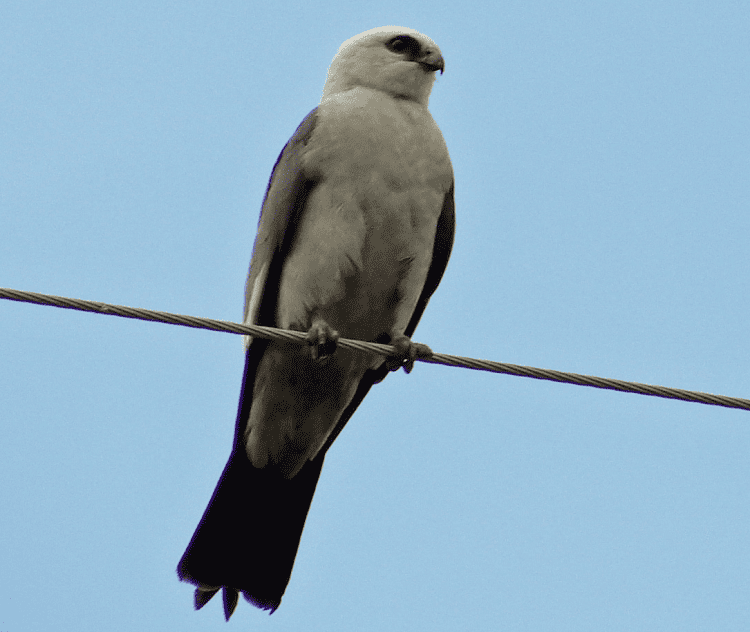

Mississippi Kite (Ictinia Mississippiensis)

These locally common summer residents are colonial breeders, present from May-August. They are a relatively small hawk, so they can subsist on insects as their main prey, though they will take small vertebrates given a chance. They are described as graceful and an agile flyer as they pursue large flying insects on the wing.

- Size: 216-341 g

- Eggs: 2 (rarely 1 or 3)

- Incubation: 29-32 days

- Fledging: 30-35 days

- Oldest known bird: 11 years

With dark grey lower wings and tail, light grey upper wings and back, and a light head and body, you may think they look drab, but if you’re lucky enough to get a close look, you’ll notice they have bright red eyes. Unlike most other kites, their tail is barely forked, and their slender wings are as long as the tail when perched.

They prefer groves and wooded streams, though they will use golf courses and urban areas with sufficiently high trees as nesting sites since they provide open spaces for foraging. However, foraging in agricultural habitats makes them susceptible to pesticide poisoning from eating contaminated insect prey.

Additionally, when the kites defend their nests near humans, they are sometimes shot, or their nests are destroyed in response, requiring better public education to manage these types of conflict.

They have been expanding their range northward for the last half-decade in Missouri as habitat changes have favored their nesting requirements. Search along the Mississippi River valley for a good chance of seeing this species.

Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus Pileatus)

This bird is unmistakable and one of my favorites to spot. A black bird with a white line extending from its beak across its head, down its neck, and onto its wing, with two additional horizontal white stripes on its face, capped with a crest of bright red feathers, there’s no mistaking it for any other.

It’s also the largest woodpecker in North America. Males and females are identical, except males have a small red mustache, and their red crown extends to the base of their bill.

- Size: 247-355 g

- Eggs: 4 (range 1-6)

- Incubation: 15-18 days

- Fledging: 24-31 days

- Oldest known bird: 10 years

They need large, mature trees, especially dead ones, for nesting and downed wood for foraging; as long as a wooded area contains that, they will use forests and wooded parks.

However, little is known about whether they successfully reproduce in these fragmented habitats. They will also come to backyard suet feeders in the winter. In the summer, they feed on insects, especially ants, plus nuts, fruits, and berries where available.

As you would expect from a large woodpecker, they excavate large holes. These are important to other cavity nesters who can’t make their own holes. At least 38 different bird species are known to use empty pileated woodpecker holes.

Historically, they were often shot for food, sport, and spiritual reasons, practices which continue in some areas to this day. Increased protection from hunting, as well as better land management practices that protect large dead trees, contributed to the population rebound.

They are a common year-round resident in the Ozarks and less common but present in woodlots elsewhere throughout the state.

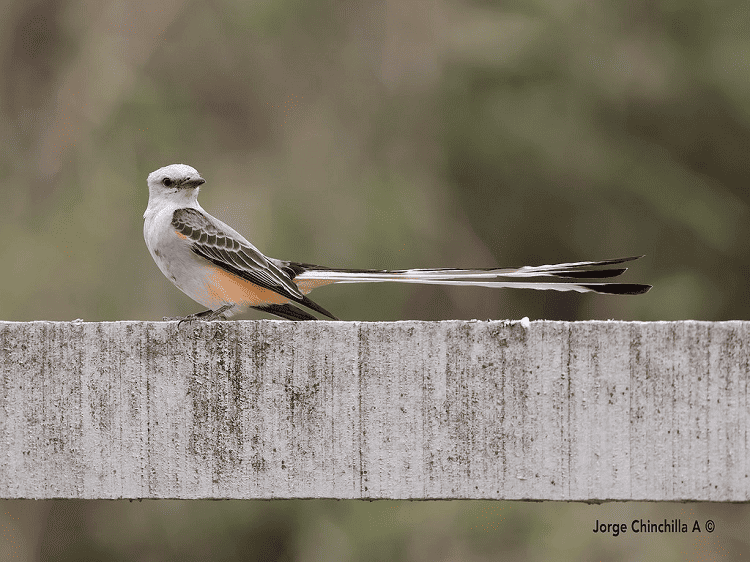

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus Forficatus)

This migratory species is fairly common in southwest Missouri, where it breeds in the summer. They are less common but usually present in other parts of the state, especially as wanderers during migration.

Their occurrence in the state is an eastward expansion of this species’ range that started in the late 1800s, possibly due to clearing forests for fields and pastures. The species is still expanding northward.

- Size: 36-56 g

- Eggs: 4-5 (seldom 3 or 6); can have a second clutch

- Incubation: 13-22 days

- Fledging: 14-17 days

- Oldest known bird: not known

There’s no way I could ignore a bird with a tail like this. Their name doesn’t really do it justice – it’s an epic pair of scissors!

Their tails, though impressive by their length alone, are even more impressive when flared out: the outer two tail feathers are white and tipped in black, and the inner feathers are black, creating a visually striking pattern.

The tail is longer in males than in females and is used by the male in aerial displays when courting a prospective mate. He flies up and down, opening and closing his tail while giving sharp calls, and may also perform backward somersaults in the air.

With a very pale gray head and body, orange-pink flanks, and dark grey wings and tail, the coloration isn’t particularly striking. However, if you see them in flight, you’ll notice a bright red patch of color under their wings.

Like other flycatchers, they perch and watch for flying insects, then fly and grab them. They are often spotted perching near roads.

They use trees or bushes for nesting and readily utilize human-made structures like power poles. After breeding, they can gather in large groups, 1,000 strong, as they prepare to migrate.

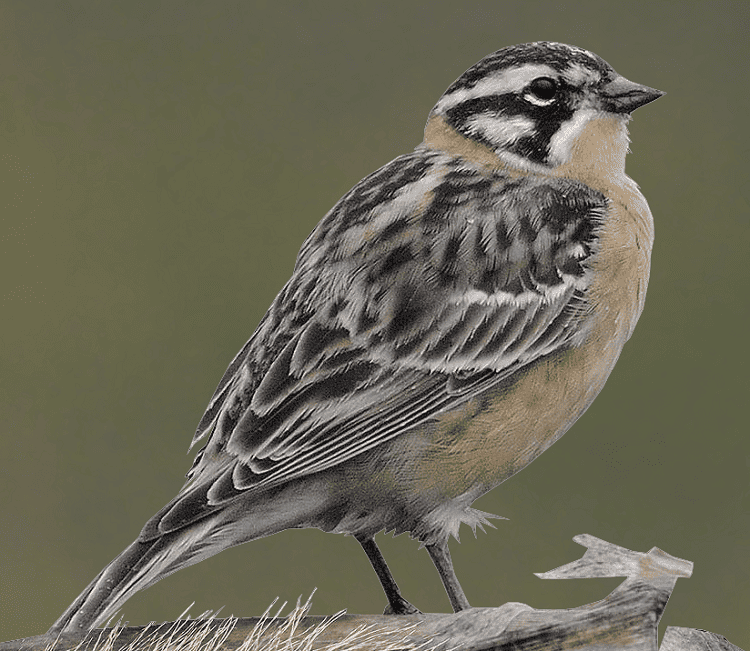

Smith’s Longspur (Calcarius Pictus)

These are migrants seen moving through the state in the spring and fall. Look on the western side to have a better chance of seeing them, as they are rarer in the eastern portion. Some may overwinter in the southwest corner of the state as well.

- Size: 19-32 g

- Eggs: 4 (though 1-6 possible)

- Incubation: 11-13 days

- Fledging: 7-9 days to leave the nest, but 12+ days to fly

- Oldest known bird: 5 years

The male has a striking pattern, even though it is not colorful. The male’s black and white patterned face is set off by being surrounded by orange that continues down his throat and chest. The mainly brown wings also have a small distinctive white patch. Females have streaked breasts and are overall browner.

They use open habitats as seed eaters that forage on the ground, though insects are consumed in the summer.

Though they don’t breed in Missouri – their breeding range is the tree line in northern Canada and Alaska – they have pretty interesting habits: they’re a colonial nester and practice polygynandry, with both males and females having 1-3 mates.

Two or three males often help raise the chicks, but sometimes a male that fathered chicks does not help at all.

They also have one of the higher copulation rates of any bird – up to 629 times for a single clutch of eggs. This is due to their mating system, as each male wants to fertilize the most eggs, so he mates to dilute or displace the previous male’s sperm.

As is normal for species breeding in the far north, they nest on the ground. They’re one of the least studied songbirds because of their restricted and remote breeding range.

Cerulean Warbler (Setophaga Cerulea)

This warbler made my list because it is the fastest-declining Neotropical migrant songbird – a sad claim to fame. It’s lost 82% of its population in only 40 years. Despite this, it is only listed as Near Threatened.

- Size: 8-11 g

- Eggs: 3-4 (1-5 possible)

- Incubation: 11-12 days

- Fledging: 10-11 days

- Oldest known bird: 8 years

Males and females look quite different. The male is a light blue and white mosaic with some black streaks on his flanks. Females have a solid green-blue back, wings, and crown, a pale line above the eye, two white wing bars, and a light throat and belly.

This bird shows up in spring to breed in the southern Ozarks and is less common elsewhere.

It’s a forest interior breeder and needs older, mature forests, but fragmentation on its breeding grounds has caused increased nest parasitism by brown-headed cowbirds, overall forest loss to agriculture has reduced breeding habitat, and the loss of wintering forest habitat by coffee plantations further contributes to declines.

It’s projected to worsen as mountaintop mining continues destroying its last strongholds of forest breeding habitat.

Still, it can be a hard bird to study, as it forages and nests high in tall trees and blends in due to its blue color to boot. It’s also one of the longer-distance Neotropical migrants, overwintering in the northern Andes of South America.

Starting in 2000, research on the species intensified and has become a model coalition among several agencies for species conservation.

Unless habitat destruction is halted, we may lose species like this in the near future. See one while you still have the chance.

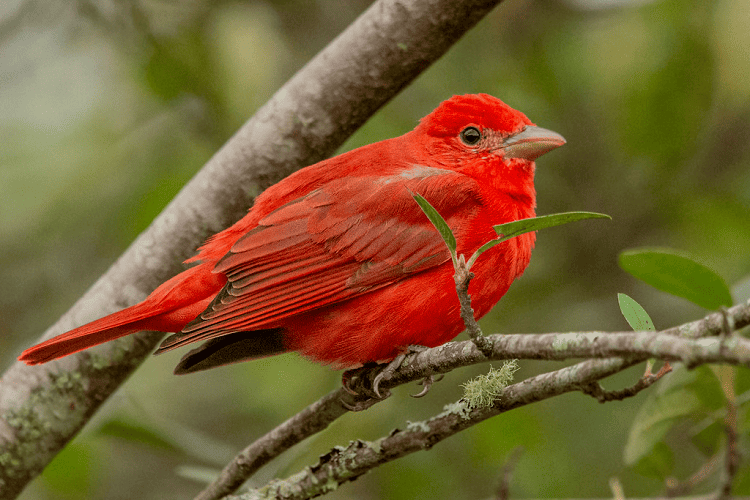

Summer Tanager (Piranga Rubra)

This bird makes the list simply because they’re a pop of color that seems almost unnatural. Males are solid red, and females are solid olive-yellow. As a summer breeder in southern Missouri, seeing one of these birds will surely make you smile.

- Size: 26-30 g

- Eggs: 3-4

- Incubation: 11-12 days

- Fledging: 9-12 days, though need several more days to fly well

- Oldest known bird: 5 years

They prefer open wooded areas along edges or gaps and prefer deciduous trees like oak in the east, and cottonwood-willow stretches along streams in the west, where they forage and nest high in the canopy. Their main food is insects, especially bees and wasps, on which they are known specialists.

They don’t have any particular adaptations for dealing with being stung, but their behavior reduces this risk: they rub a bee against a branch to remove the stinger. If they find a hive, they’ll eat the adults, then break apart the hive and eat the larvae. They’ll also eat several different types of berries.

They aren’t seed eaters, so they won’t come to those types of backyard bird feeders but can be enticed with offerings similar to those that would attract orioles: oranges, ripe bananas, and grape jelly. An offering of live mealworms would likely be snapped up in a jiffy.

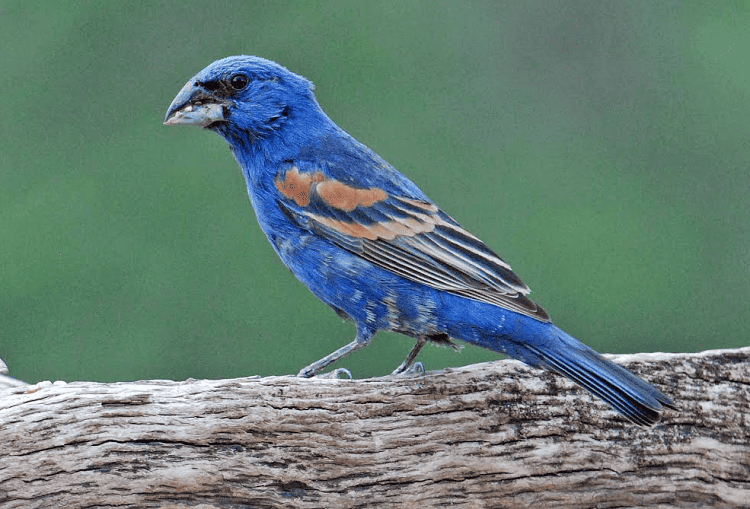

Blue Grosbeak (Passerina Caerulea)

The blue grosbeak is also a pop of color but in a different way: the male is solid blue except for two brown wing bars, while the female is all brown.

Like all birds that look blue – think indigo bunting and blue jay – this color is not achieved using pigment granules deposited in the feathers, which is how red and yellow are achieved; rather, blue is a structurally-based coloration created by the microstructure of feather barbules.

Interestingly, birds see into the ultraviolet spectrum, but humans cannot, so even though all blue grosbeaks look the same to us, other birds can detect differences in reflectance from their feathers.

Research showed the intensity of the blue color is an honest signal of male quality: the brightest males were healthiest and had the best territories.

- Size: 221-538 g

- Eggs: 3-6; often lays two clutches in a season

- Incubation: 19-20 days

- Fledging: 14-25 days

- Oldest known bird: 11 years

It used to be thought that blue grosbeaks were related to cardinals, and some older texts may still refer to them as Guiraca caerulea. DNA studies showed it was more closely related to lazuli buntings and so was moved to the genus Passerina.

Missouri is at the northern edge of its breeding range, and these grosbeaks can be seen during the summer in the state’s southern areas and less commonly in the north. Despite having a fairly wide geographic range, it has never been abundant, so locating one may require some effort.

Listen for their long, rich warble to have a better chance of locating one – only males sing. Habitat requirements are varied, as they use anything from hedgerows to open woodlands.

Despite its striking blue coloration, there hasn’t been a lot of research on this species, especially where it overwinters.

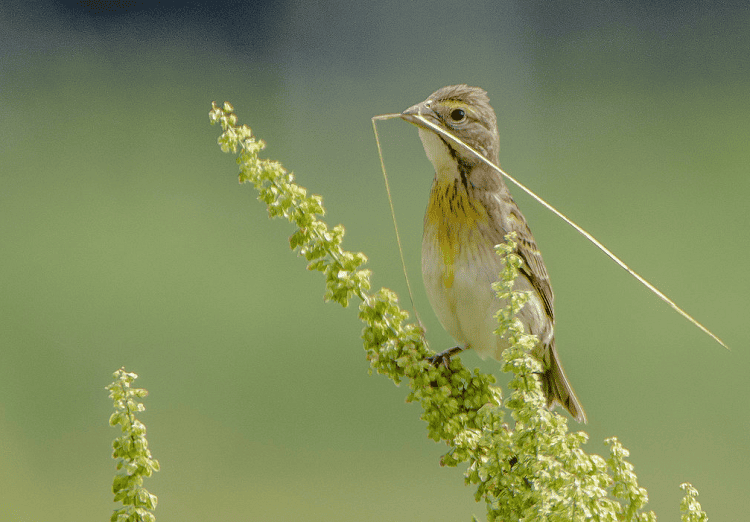

Dickcissel (Spiza Americana)

These birds are only found breeding in the eastern US but are not seen as regularly as most species. They seem to respond to local food abundance, so an area with birds breeding one year may be empty the next, but overall they are found in grasslands.

They’ve also had large range changes, with an eastward expansion in the early 1800s, but retreated back west by the end of that century. The northern breeding areas are currently decreasing in population, and they lost 1/3 of their population from 1966-1978. They are still common in Missouri.

- Size: 25-38 g

- Eggs: 4 (range 3-7)

- Incubation: 12-13 days

- Fledging: 8-10 days; requires 4-11 more days for full flight

- Oldest known bird: 8 years

These birds are sparrow-sized but have more color on their head and chest than sparrows: they sport a white line above the eye, a white throat and flanks with a yellow chest, and the males have a black bib.

They’re a late breeder, arriving in June instead of May. They are also polygynous, a rare strategy for songbirds, where each male can mate with multiple females.

The best males can have up to six mates, while many other males get none. However, unlike birds like the blue grosbeak, successful males were not more colorful than unsuccessful males.

Many grasslands have been converted into fields and pastures. If dickcissels nest in a hayfield, mowing will likely destroy their nests before fledging.

These are seed and insect eaters, hunting on the ground or in fields. This food preference, and their strategy of forming large flocks during the non-breeding season, has led to conflict as they can be pests of crops.

Because of this, they are often shot, clubbed to death while roosting at night, and run over by cars while roosting. They are also deliberately poisoned; one farmer killed over 1 million dickcissels this way.

FAQs

Question: Which Birds are no Longer Found in Missouri?

Answer: Five species are extinct on the planet (passenger pigeon, Eskimo curlew, ivory-billed woodpecker, Carolina parakeet, Bachman’s warbler), and three are extirpated from the state (red-cockaded woodpecker, common raven, brown-headed nuthatch). The reasons for this differ among species but mainly include overhunting and habitat loss.

Question: What are the Most Common Backyard Birds of Missouri?

Answer: Year-round, you’ll see robins, cardinals, blue jays, tufted titmouse, white-breasted nuthatch, house sparrows, mourning doves, black-capped chickadees, and downy and hairy woodpeckers, and in the summer you’ll also get ruby-throated hummingbirds, common grackles, eastern phoebes, and chipping sparrows.

Having a diverse, natural backyard with some additional feeders will almost guarantee you see these species and more!

Question: What’s the Rarest Bird in Missouri?

Answer: This is hard to answer, as many species of birds have individuals that occasionally wander or get blown off-course, sometimes by hundreds of miles and sometimes across oceans.

Thus, several species are represented in Missouri records as one-off occurrences, so birders would have no luck finding them today, like the golden-crowned sparrow that was found 2,000 miles from its normal range.

However, other species, like the black-bellied whistling duck, are often found outside its range and were spotted in Missouri again last month.

Conclusion

Missouri has some beautiful birds, and those living in the state are fortunate enough that healthy habitats exist for these species. However, some are still declining, whether at slow or alarming rates.

Hopefully, keen birders and conservationists will continue to advocate for habitat protection. If you enjoy the state’s iconic birds, let’s ensure they stay around for generations.

References:

- Birds of Missouri. https://mobirds.org/Birds/

- Birds of the World (2022). Edited by S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/home

- Jones, S. P. 2021. The story of the bluebird: how it came to be chosen as Missouri’s state bird and the amazing developments that followed. The Bluebird, 88(2): 97-100.

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: