- Best Amazon Bird Baths Guide - September 26, 2023

- Best Copper Bird Baths - August 30, 2023

- Best Bird Baths Available at Home Depot - August 26, 2023

Black-backed woodpeckers are northern birds and are specialists of burned forests. When trees are dead or dying (because of fire or infestation by mountain bark beetles), several other species of beetles (especially in the families Buprestidae and Cerambycidae) lay their eggs on these trees.

The larvae burrow under the bark and are the primary food source excavated by black-backed woodpeckers for several years thereafter. I’ve been lucky enough to see them in unburned forest, foraging on dead trees, and their sleek black plumage seems to be made for blending in with dead trees.

Taxonomy

This species was first described in 1832 by William John Swainson. The specific name ‘arcticus‘ refers to ‘northern’ or ‘arctic,’ and the genus name ‘Picoides’ comes from the Latin ‘picus’ for ‘woodpecker’ and the Greek ‘oides’ for ‘resembling.’

Confusingly, this species used to be referred to as the black-backed three-toed woodpecker, and is sometimes referred to as the Arctic three-toed woodpecker.

In 2015, a new molecular phylogeny reassigned many woodpecker species to different genera, and only the American and Eurasian three-toed woodpeckers remained in the Picoides genus with the black-backed woodpecker.

The black-backed woodpecker has three subpopulations that are genetically differentiated: the largest population that extends from the Rocky Mountains to Quebec; one in the west (Oregon); and a disjunct population in South Dakota. However, they are not currently listed as subspecies.

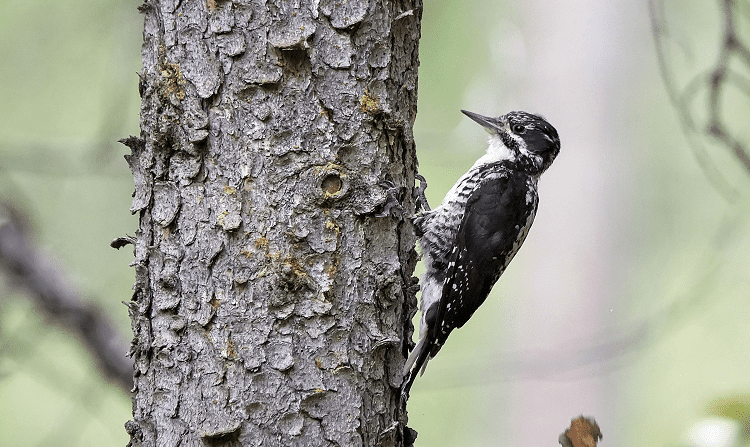

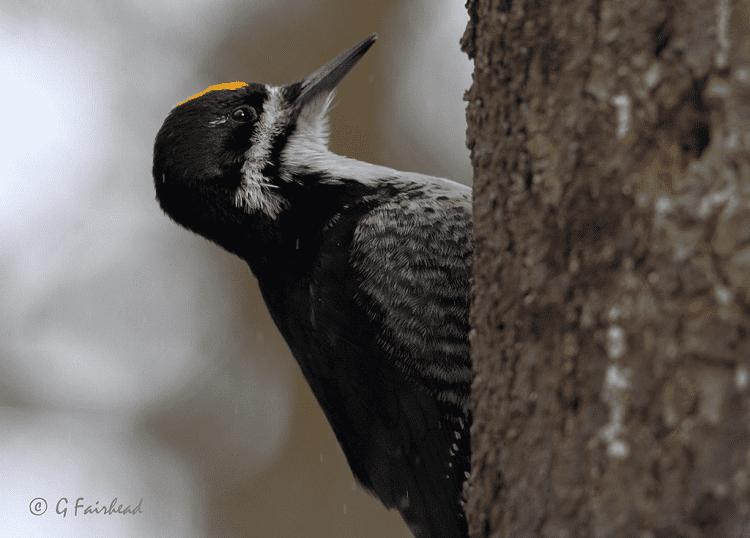

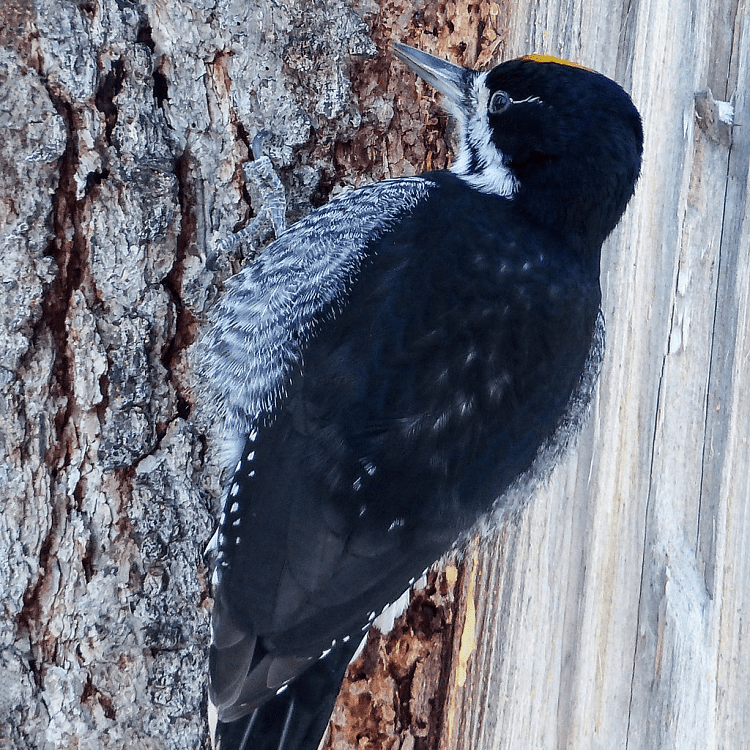

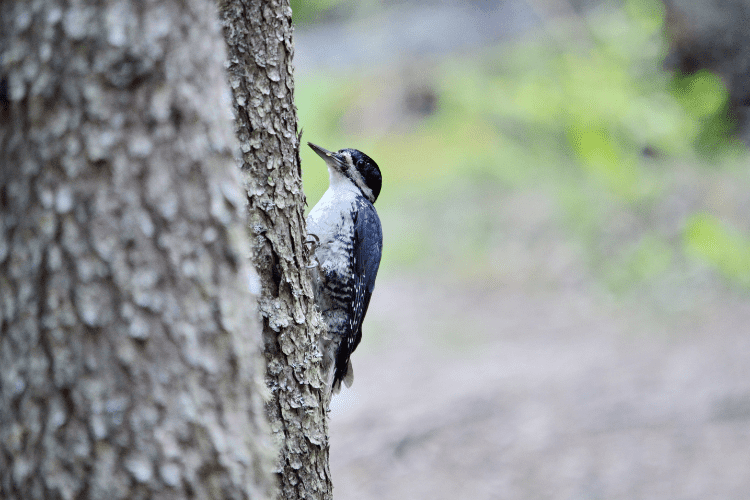

How to Identify a Black-backed Woodpecker

Size

These are medium-sized woodpeckers, about 9.1 inches long, and weighing 61-88 g.

Color

As the name suggests, black-backed woodpeckers do, in fact, have a black back. Their belly is white as is their throat, and their flanks are finely barred. While mainly black, their wings have some white spotting on their primary and secondary feathers.

Their head, while mainly black, has a white stripe that runs from the top of the beak diagonally to the side of the neck and a small white spot or thin short stripe behind the eye. Adult males and juveniles of both sexes have a yellow crown, while adult females do not.

Toes

If you’re patient and can get close to a woodpecker, you can also look at how many toes it has. Most birds have four – three facing forward and one backwards. Most woodpeckers also have four toes, except two face forward and two face backward.

However, black-backed woodpeckers are one of only three species of woodpeckers that have three toes (the other two species are American three-toed and Eurasian three-toed woodpeckers). It is thought that three toes allows these woodpeckers to lean farther back and therefore impart a more powerful blow at the tree bark.

Other Similar Species

The other woodpeckers most easily confused with a black-backed woodpecker are hairy, downy, and three-toed. Don’t worry if this seems overwhelming; as a birder with many years experience, I know that black-and-white woodpeckers can be very confusing at first glance.

If you can see the back, note the back color pattern; if you can see the head, note the number of white stripes (but don’t get confused by the white throat, which they all have).

| Back pattern | Flank pattern | Wing pattern | Head | |

| Hairy woodpecker | White stripe | White | Partially spotted | Two white stripes |

| Black-backed Woodpecker | White stripe | White | Partially spotted | Two white stripes |

| Three-toed woodpecker | Barred | Barred | Minimally spotted | Two white stripes |

| Black-backed woodpecker | Black | Barred | Minimally spotted |

One white stripe |

Where Does a Black-backed Woodpecker Live: Habitat

These birds are non-migratory, occurring over much of Canada, southern Alaska, and parts of western North America, largely following the coniferous forest range, in the boreal and montane regions.

In California, it lives from 1,200-2,800m on the inland mountains in the Cascades, Sierra Nevada, and Warner Mountains, which is the southernmost limit of their range. They were first reported nesting in Nevada in 2002.

Black-backed woodpeckers forage on dead trees. They prefer burned areas when available and will use these areas up to 8 years post-fire.

They will also live in bogs where burned areas are limited. Even though forest stands killed by mountain bark beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae) outbreaks also create dead trees, black-backed woodpeckers prefer areas killed by fire. They will move into and occupy burned areas at high densities.

Home range size of individual black-backed woodpeckers was best explained by variation in snag density, with home ranges from 24.1-304.1 ha. Home range sizes varied from 150.4-766.1 ha after chicks had fledged in areas 6-8 years postfire, and in an unburned area, they were 100.4-256.4 ha.

Black-Backed Woodpecker Diet and Feeding

Black-backed woodpeckers tend to stay in one place longer than other woodpeckers while foraging, as they concentrate their efforts on digging deeper into the wood to get larger wood-boring beetle larvae, their primary food source.

In unburned areas, they rely on dead snags for foraging, which requires enough habitat that there is a continuous supply of dead trees. Summer forest fires resulted in more food (beetle larvae) available than fall-prescribed forest fires or areas killed by mountain bark beetles.

High-quality snags (larger snags less deteriorated by fire) contained more beetle larvae, and woodpeckers foraged there more often.

Though wood-boring beetle larvae are their primary food source, they will also eat the larvae of bark beetles, other insects, fruits, nuts, and cambium (the growing part of the tree trunk).

Black-backed Woodpecker Breeding

Woodpeckers drum (repeated rapid strikes, not associated with feeding) during social interactions. A black-backed woodpecker’s drum contains about 30 beats at a rate of 16 beats/second. This likely signals to other woodpeckers which species it is, but whether this encodes information about individual identity or quality is unknown.

Within species, differences in coloration between the sexes is usually attributed to sexual selection. In the case of black-backed woodpeckers, the males have a yellow head; otherwise, the sexes are identical, though males can be a little larger than females.

However, I could find no information on whether this trait is used by females for selecting males or by males in establishing territories, though the males will raise their crest towards a female. There is also no information on duration of pair-bonds beyond a single breeding season.

Reproductive success, however, is linked to habitat quality. Black-backed woodpecker reproductive success declined after three years post-fire, likely due to declining beetle larvae. Reproductive success was higher in mature than young burned forest, indicating that removal of older forests may reduce suitable habitat.

Reproductive success was also higher in areas burned by summer fires compared to prescribed fall burns or mountain bark beetle outbreaks. Whether higher-quality individuals occupy higher-quality habitat, however, is not known.

Black-Backed Woodpecker Nesting

They prefer large snags (>20cm diameter at breast height) in burned mature stands. In California, average size of nesting tree was 33-36cm. They nest in April-June when both sexes contribute to the excavation of a hole in a dead tree, and they do not reuse cavities.

Black-Backed Woodpecker Eggs

Usually 2-3, but up to 6 eggs are laid. Both sexes incubate the eggs (approximately 13 days) and brood the young.

Both sexes contribute equally to feeding nestlings, though some studies found females provisioned more often though may have brought fewer prey each visit.

Adults bring larger prey as the nestlings get older. Males removed almost all the fecal sacs. Fledging occurs around 25 days.

Black-Backed Woodpecker Population

The black-backed woodpecker is prone to irruptions when individuals travel outside their normal range in response to food availability. For example, Dutch elm disease killed off elms in the 1950-60s, and black-backed woodpeckers appeared in several areas that is not normally part of their range.

Salvage logging occurs in burned areas, often targeting the same trees that black-backed woodpeckers require, which could affect reproductive success.

Restricting summer wildlife, which creates the best quality habitat for black-backed woodpeckers, could also result in population declines.

Managers also remove beetle-killed trees via salvage logging, which removes important food resources and could negatively affect breeding success. However, unburned habitat may provide more stable breeding conditions.

A nematode of the genus Procyrnea was first noted to result in a lethal infection in 2012, and this nematode has resulted in substantial die-offs in other species. Whether this is a new cause for concern in black-backed woodpeckers is unknown.

Is the Black-backed Woodpecker Endangered?

No, it is listed as Least Concern. Their main threat is habitat loss, as fires and insect outbreaks are suppressed by humans, reducing the amount of food and dead trees needed for nesting.

In California, in particular, there is a scarcity of good quality habitat for these woodpeckers, as burned areas are ephemeral, patchy, and often logged by people. Additionally, much of the woodpecker population there exists at low density in unburned forest. Thus there is a Conservation Strategy for this species in California.

Black-backed Woodpecker Habits

Their usual call is a single sharp pik or kuk. They can also emit a ‘scream-rattle-snarl’ vocalization, thought to be used in territory defense. They will also flare their wings and crest in response to territorial intrusions. Otherwise, they’re a pretty chill birds, concentrating on eating most of the time, not interacting with other species.

Black-backed Woodpecker Predators

Northern goshawks will predate adult black-backed woodpeckers, and they are likely vulnerable to other avian predators as well, like Cooper’s hawks. Chicks in the nest are vulnerable to any carnivore that can find them, including black bears and opportunistic mammals like squirrels, martens, and weasels.

Black-backed Woodpecker Lifespan

The oldest known individual was four years 11 months old when it was recaptured, and so maximum lifespan is at least five years.

FAQs

Answer: No, but the reason why is still being researched. Initially, it was thought their skull served as a shock absorber to protect the brain, but recent research suggests that this is not the case and that their small brain size is the critical factor.

Answer: Yes! Black-backed woodpeckers make cavities for nesting but don’t use the cavities again. Other tree-nesting species that can’t make their own holes then have access to nesting spaces, including mammals and seed-dispersing birds.

Answer: Though we don’t know for sure, one hypothesis is that it provides camouflage against a burned tree, so they’re less likely to be seen and captured by predators.

Conclusion

As a biologist, I always find animals that are specialists very interesting. What were the evolutionary pressures that led to specialization? How many millennia did it take? Will humans’ continued management of the landscape led to the demise of this species?

Specialists are more at risk of extinction than generalists, and for the sake of future generations seeing all the diversity of life, I hope we can preserve all habitats.

This woodpecker was even selected as the symbol for the Society of Canadian Ornithologists, partly because it can help us understand the issues our Canadian habitats face in this rapidly changing world.

References:

- Biewener, A. A. (2022). Physiology: Woodpecker skulls are not shock absorbers. Current Biology, 32(14), R767-R769.

- Bonnot, T. W., Millspaugh, J. J., & Rumble, M. A. (2009). Multi-scale nest-site selection by black-backed woodpeckers in outbreaks of mountain pine beetles. Forest Ecology and Management, 259(2), 220-228.

- Craig, D. L. (2012). A conservation strategy for the black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) in California–Version 1.0. The Institute for Bird Populations and California Partners in Flight, Point Reyes Station, CA, USA.

- Davies, K. F., Margules, C. R., & Lawrence, J. F. (2004). A synergistic effect puts rare, specialized species at greater risk of extinction. Ecology, 85(1), 265-271.

- Dudley, J. G., & Saab, V. A. (2007). Home range size of black-backed woodpeckers in burned forests of southwestern Idaho. Western North American Naturalist, 67(4), 593-600.

- Dudley, J. G., Saab, V. A., & Hollenbeck, J. P. (2012). Foraging-habitat selection of Black-backed Woodpeckers in forest burns of southwestern Idaho. The Condor, 114(2), 348-357.

- Fuchs, J., & Pons, J. M. (2015). A new classification of the Pied Woodpeckers assemblage (Dendropicini, Picidae) based on a comprehensive multi-locus phylogeny. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 88, 28-37.

- Kilham, L. 1966. Nesting activities of Black-backed Woodpeckers. Condor 68: 308–310.

- Loverin, J. K., Stillman, A. N., Siegel, R. B., Wilkerson, R. L., Johnson, M., & Tingley, M. W. (2021). Nestling provisioning behavior of Black‐backed Woodpeckers in post‐fire forest. Journal of Field Ornithology, 92(3), 273-283.

- Miles, M. C., Schuppe, E. R., Ligon IV, R. M., & Fuxjager, M. J. (2018). Macroevolutionary patterning of woodpecker drums reveals how sexual selection elaborates signals under constraint. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1873), 20172628.

- Nappi, A., & Drapeau, P. (2009). Reproductive success of the black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) in burned boreal forests: are burns source habitats?. Biological Conservation, 142(7), 1381-1391.

- Nappi, A., Drapeau, P., Giroux, J. F., & Savard, J. P. L. (2003). Snag use by foraging black-backed woodpeckers (Picoides arcticus) in a recently burned eastern boreal forest. The Auk, 120(2), 505-511.

- Nappi, A., & Drapeau, P. (2011). Pre-fire forest conditions and fire severity as determinants of the quality of burned forests for deadwood-dependent species: the case of the black-backed woodpecker. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 41(5), 994-1003.

- Pausas, J. G., & Parr, C. L. (2018). Towards an understanding of the evolutionary role of fire in animals. Evolutionary Ecology, 32(2), 113-125.

- Pierson, J. C., Allendorf, F. W., Saab, V., Drapeau, P., & Schwartz, M. K. (2010). Do male and female black‐backed woodpeckers respond differently to gaps in habitat?. Evolutionary Applications, 3(3), 263-278.

- RICHARDSON, T. W. (2003). First records of Black-backed Woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) nesting in Nevada. Great Basin Birds, 6(1), 2003.

- Rota CT (2013) Not all forests are disturbed equally: Population dynamics and resource selection of Black-backed Woodpeckers in the Black Hills, South Dakota. PhD dissertation. Columbia: University of Missouri. 146 p.

- Rota, C. T., Millspaugh, J. J., Rumble, M. A., Lehman, C. P., & Kesler, D. C. (2014). The role of wildfire, prescribed fire, and mountain pine beetle infestations on the population dynamics of black-backed woodpeckers in the Black Hills, South Dakota. PloS one, 9(4), e94700.

- Rota, C. T., Rumble, M. A., Lehman, C. P., Kesler, D. C., & Millspaugh, J. J. (2015). Apparent foraging success reflects habitat quality in an irruptive species, the Black-backed Woodpecker. The Condor: Ornithological Applications, 117(2), 178-191.

- Short, L. L. 1974. Habits and interactions of North American Three-toed Woodpeckers (Picoides arcticus and Picoides tridactylus). American Museum Novitates 547: 1–42.

- Siegel, R. B., Bond, M. L., Wilkerson, R. L., Barr, B. C., Gardiner, C. H., & Kinsella, J. M. (2012). Lethal Procyrnea infection in a black-backed woodpecker (Picoides arcticus) from California. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine, 43(2), 421-424.

- Stark, R. D., Dodenhoff, D. J., & Johnson, E. V. (1998). A quantitative analysis of woodpecker drumming. The Condor, 100(2), 350-356.

- Stillman, A. N., Siegel, R. B., Wilkerson, R. L., Johnson, M., Howell, C. A., & Tingley, M. W. (2019). Nest site selection and nest survival of Black-backed Woodpeckers after wildfire. The Condor, 121(3), duz039.

- Tarbill, G. L., Manley, P. N., & White, A. M. (2015). Drill, baby, drill: The influence of woodpeckers on post‐fire vertebrate communities through cavity excavation. Journal of Zoology, 296(2), 95-103.

- Tingley, M. W., Wilkerson, R. L., Bond, M. L., Howell, C. A., & Siegel, R. B. (2014). Variation in home-range size of Black-backed Woodpeckers. The Condor: Ornithological Applications, 116(3), 325-340.

- Tingley, M. W., Wilkerson, R. L., & Siegel, R. B. (2015). Explanation and guidance for a decision support tool to help manage post-fire Black-backed Woodpecker habitat. The Institute for Bird Populations, Point Reyes Station, California.

- Tingley, M. W., Stillman, A. N., Wilkerson, R. L., Sawyer, S. C., & Siegel, R. B. (2020). Black-backed woodpecker occupancy in burned and beetle-killed forests: disturbance agent matters. Forest Ecology and Management, 455, 117694.

- Tremblay, J. A., Ibarzabal, J., Dussault, C., & Savard, J. P. L. (2009). Habitat requirements of breeding Black-backed Woodpeckers (Picoides arcticus) in managed, unburned boreal forest. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 4(1), 1-16

- Tremblay, J. A., Ibarzabal, J., & Savard, J. P. L. (2015). Contribution of unburned boreal forests to the population of Black-backed Woodpecker in eastern Canada. Ecoscience, 22(2-4), 145-155.

- Tremblay, J. A., Ibarzabal, J., Saulnier, M. C., & Wilson, S. (2016). Parental care by Black-backed Woodpeckers in burned and unburned habitats of eastern Canada. Ornis Hungarica, 24(1), 69-80.

- Van Wassenbergh, S., Ortlieb, E. J., Mielke, M., Böhmer, C., Shadwick, R. E., & Abourachid, A. (2022). Woodpeckers minimize cranial absorption of shocks. Current Biology, 32(14), 3189-3194.

- Yunick, R. P. (1985). A review of recent irruptions of the Black-backed Woodpecker and Three-toed Woodpecker in eastern North America. Journal of Field Ornithology, 138-152.

- Youngman, J. A., & Gayk, Z. G. (2011). High density nesting of black-backed woodpeckers (Picoides arcticus) in a post-fire Great Lakes jack pine forest. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 123(2), 381-386.

Looking for more interesting readings? Check out: